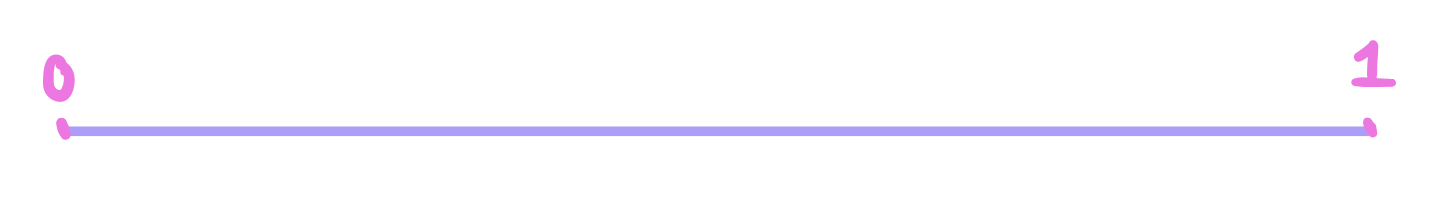

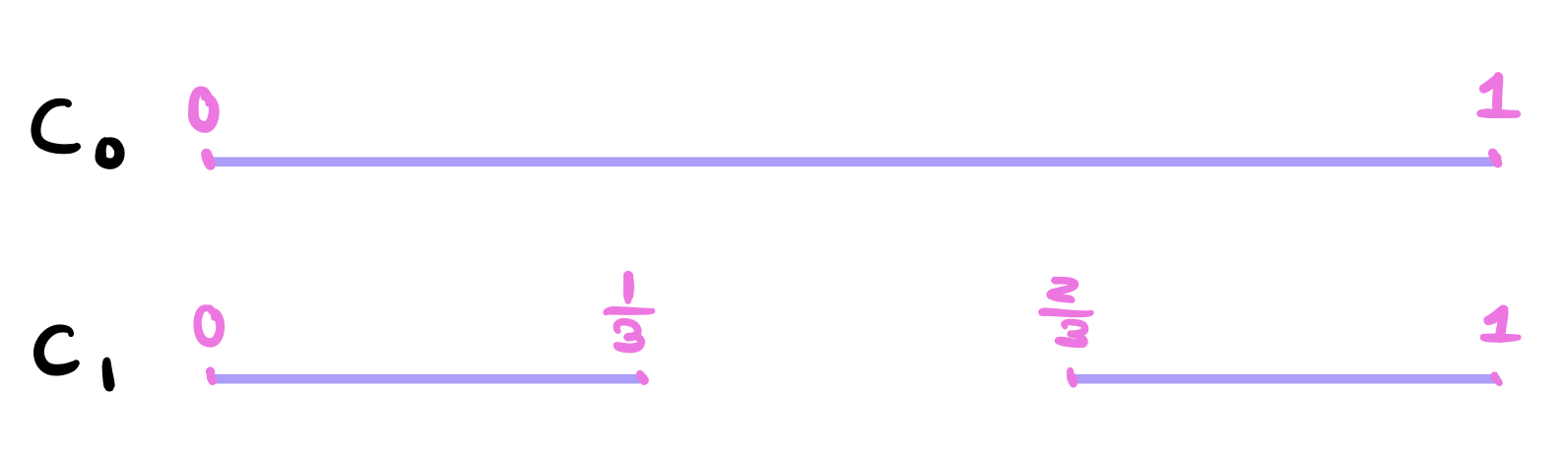

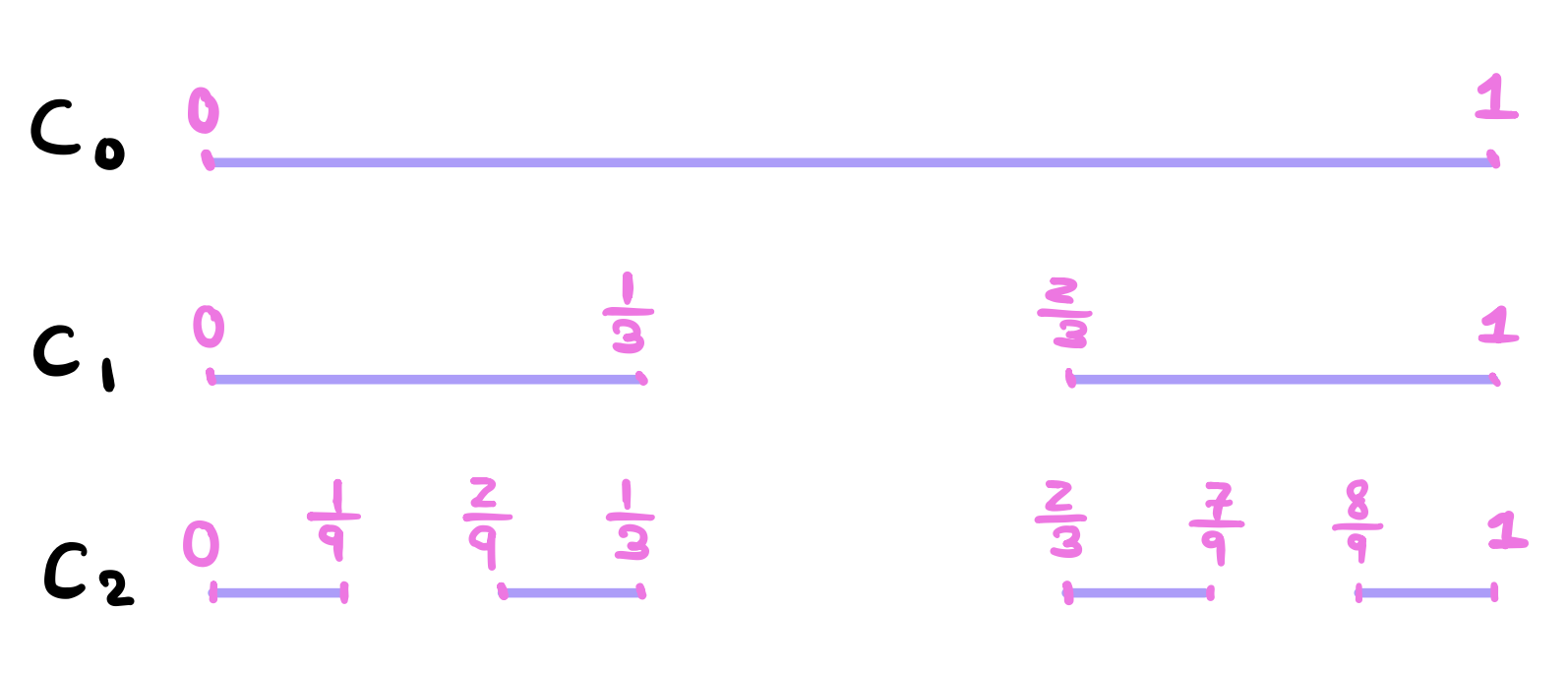

Let \(C_0\) be the closed Interval \([0,1]\) above. We will define \(C_1\) to be the set \(C_0\) after removing the open middle third \((\frac{1}{3},\frac{2}{3})\) so

Now, construct \(C_2\) the same way by taking away the middle third from each interval so

If we continue this process indefinitely, then the Cantor Set can be defined as

So \(C\) is the set remaining after removing all the middle intervals in every single stage. So we can also write \(C\) as

How Big is \(C\)?

One thing we know from drawing a few iterations is that the end points seem to always be included in \(C\). For example 0 and 1 are part of \(C_0\) and then they continue to be part of every new iteration. This doesn’t help much. The easier path to knowing how big \(C\) is is to figure out the size of what’s taken out of \(C\)? It’s easier because we know what we remove from \(C\) in every iteration. So let’s see what this amounts to.

When \(n = 1\), we removed the open interval \((\frac{1}{3},\frac{2}{3})\). The size of this interval is \(1/3\). I’m not going to lie but this threw me off. Why is the length equal to 1/3? from what I read so far, it seems like it is defined this way and also that \([\frac{1}{3},\frac{2}{3}] \backslash (\frac{1}{3},\frac{2}{3}) = \{\frac{1}{3},\frac{2}{3}\}\). This difference is a set of two numbers that has no “length”. It’s not an interval anymore and its length is zero.

When \(n = 2\), we removed two intervals of size \(1/9\). When \(n = 3\), we would be removing 4 intervals each of size \(1/27\). So it seems like to construct \(C_n\), we need to remove \(2^{n-1}\) intervals each of size \(1/3^n\). If we sum all these terms, we’d get

This is a geometric series. The sum shockingly (or not) is 1. Here is one thing. We did say at the beginning that only the end points reamin in the set each iteration but the end points kind of don’t really count. Because remember that the open interval and the close interval have the same length and if we’re going to be left with endpoints scattered all over, they won’t account for anything. Their length is “zero”.

Is \(C\) countable?

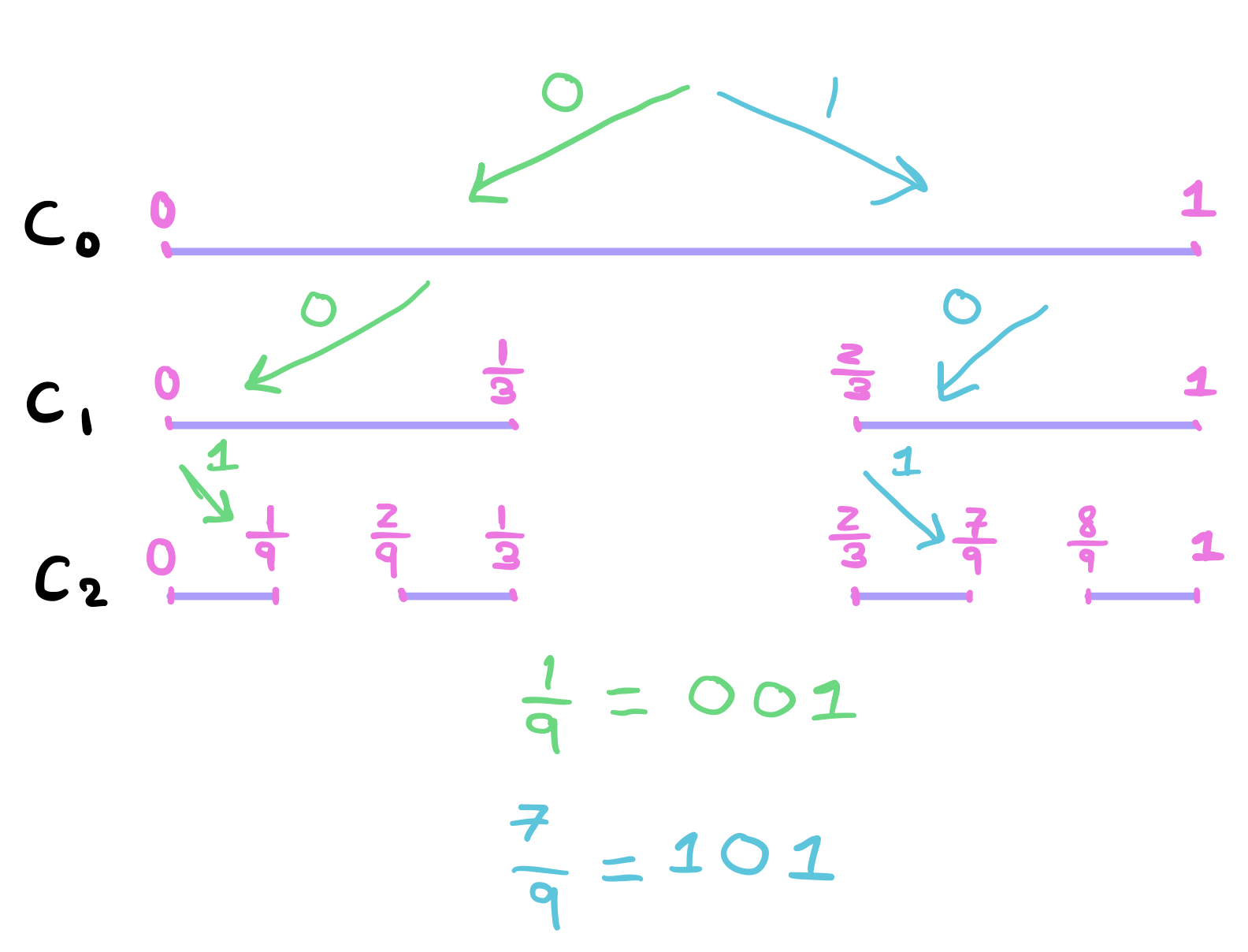

So we learned that \(C\)’s length is zero. We also learned that \(C\) at least contains all the end points in each iteration. The mental picture of \(C\) at this point is this very thin set since after all we said the length of the set must be zero. So might lead us to think that \(C\) must be countable … but it is not! In fact \(C\) is uncountable. To see, we will create a 1-1 correspondance between \(C\) and the sequences of the form \((a_n)^{\infty}_{n=1}\) where \(a_n=0\) or \(1\) (so a binary sequence, string of zeros and ones). For any \(c \in C\) we will assign \(a\) to 0 if it falls in the left side of \(C_n\) and 1 if falls on the right side of \(C_n\). For example. Suppose we’re looking at \(c = 1/9\). Then, we’ll go left, left and then right to reach it. For each left turn we will append a zero and each right turn we will append a 1.

You can see also that for \(7/9\), we go right, left and then right. If we do this for each and every element \(c \in C\), then each element will yield an infinite sequence of zeros and ones. And if we apply Cantor’s diagonalization argument, we can prove that \(C\) is uncountable because the diagonal element (after flipping each 0 to 1 and each 1 to zero) will not be present in the table and hence \(C\) is uncountable. (TODO: Write this formal proof. It should be identical to this proof).

Other Definitions and Properties

- Open Sets

- Limit Points

- Closed Sets

- Compact Sets

- Closure

- Absolute Value Function

- Sequences, Subsequences and Convergence

- Series and Series Convergence

- Show the Limit Template

References: