For the absolute value function definition and other properties see here.

For the definitions of sequences and what it means to for a sequence to converge, see this, for subsequences see this.

For the “show the limit” template and an example, see this.

Problem Discussion:

This is a great theorem because we’re saying that given any sequence whether convergent or divergent, we can still extract a convergent subsequence from it. For example if we’re given the sequence \(\{0,1,0,1,0,1,0,1,0,1,.....\}\) which clearly won’t converge, we can still make up the subsequence \(\{0,0,0,0,....\}\) which clearly converges to 0. But how do we prove this? This proof relies on the nested interval property which states that the intersection a nested sequence of closed intervals is non-empty. We will construct a subsequence from having many nested intervals and then we’ll use the nested sequence property to conclude something about its convergence.

Proof:

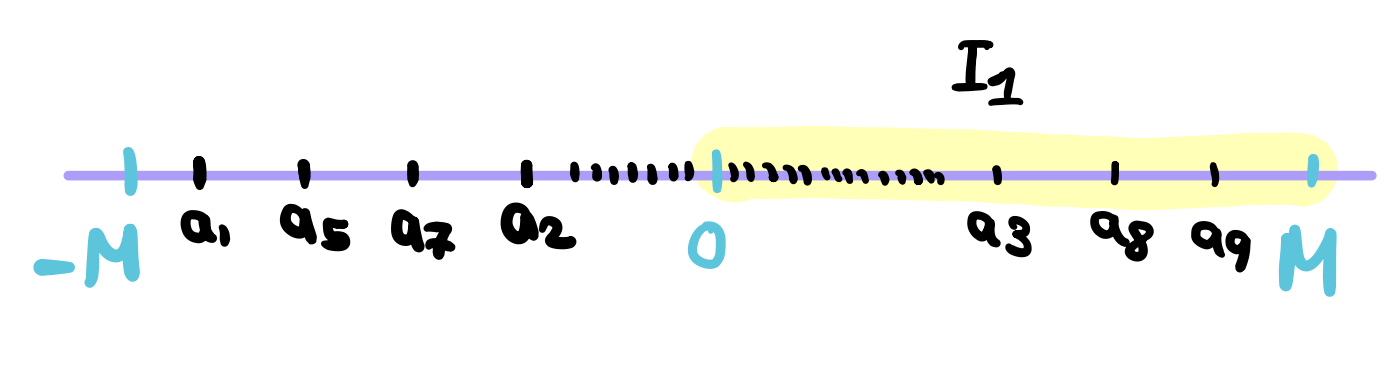

Let \((a_n)\) be a bounded sequence. By theorem 2.3.1, we know that there exists a number \(M > 0\) satisfying \(|a_n| \leq M\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). We will bisect this closed interval \([-M,M]\) into two closed intervals \([-M,0]\) and \([0,M]\) noting here that the mid point belongs to both intervals. Now, \((a_n)\) has infinitely many terms by definition. So one of these halfs must contain an infinite number of terms of the sequence \((a_n)\). Let this interval be \(I_1\) (Choose the left half if both had infinitely many terms).

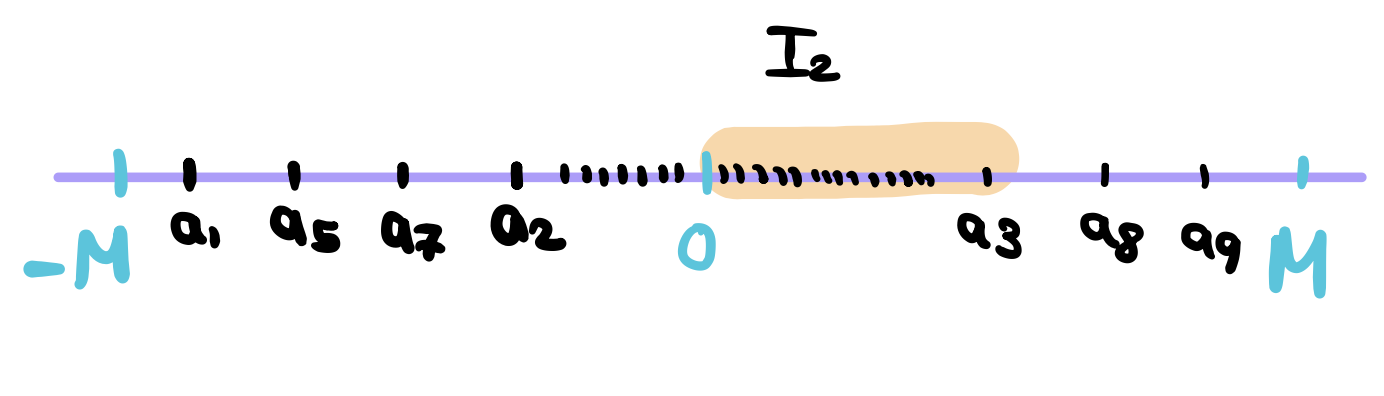

Now, we’re construct a subsequence from \((a_n)\). The first term \(a_{n_1}\) will an arbitrary element chosen from \(I_1\) so \(a_n \in I_1\). Bisect \(I_1\) again into two intervals and let \(I_2\) be the interval containing infinite terms (there should be at least one).

Let \(a_{n_2}\) be chosen from \(I_2\) such that \(n_2 > n_1\) (Side Note: Remember that \(n_2\) indicates the positon of the element in the subsequence. We can choose \(n_2\) to be bigger than \(n_1\) because \(I_2\) has infinitely many terms so even if \(a_{n_1}\) was really big like \(a_{3435453...}\), we can still find a bigger subscript since there are infinitely many terms. Moreover, our sequence is not monotone so we don’t need to worry about picking an element from the right half before the left half. This doesn’t matter. We only care about respecting the order of the elements in the sequence).

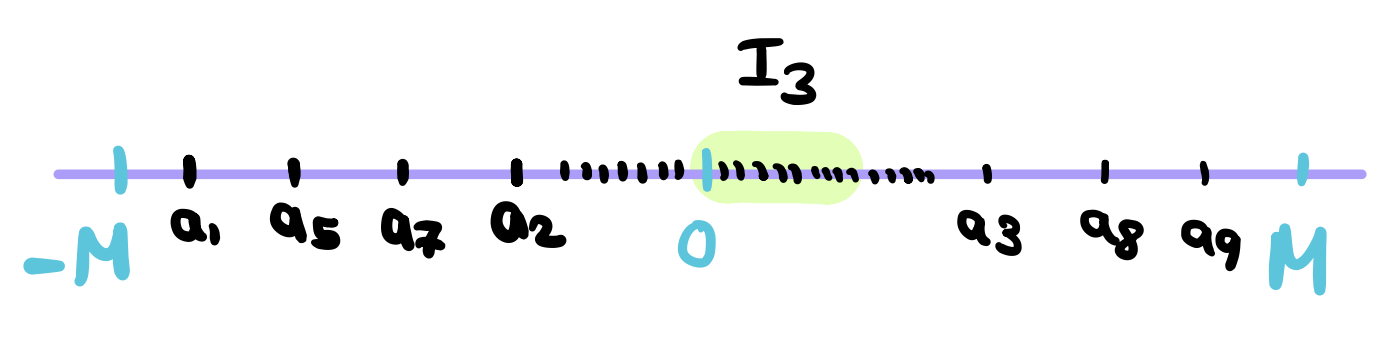

Next, we’re going to bisect \(I_2\) in the same way and choose \(I_3\) to be the half with infinitely many terms.

In general, we will construct the closed interval \(I_k\) by taking the half of interval \(I_{k-1}\) that contains infinitely many terms. We will then construct a subsequence \((a_{n_k})\) such that \(a_k \in I_k\) and

Now, we want to prove that \((a_{n_k})\) is a convergent subsequence. To do so, we need to find a candidate for limit. We do know by construction that

This forms a nested sequence of closed intervals and so by the Nested Interval Property, there exits at least one point \(x \in \mathbb{R}\) such that it is contained in every interval \(I_k\). So let’s prove that \((a_{n_k}) \rightarrow x\).

Let \(\epsilon > 0\) be arbitrary chosen. We will show that there exists a number \(N \in \mathbb{N}\) such that for any \(k \geq N\), we have

To see this, we know by construction that the length of interval \(I_k\) is \(M(1/2)^{k-1}\). But we also know that \((M(1/2)^{k-1}) \rightarrow 0\) (TODO: link). This means that the intervals are getting smaller and smaller until the length of these intervals converges to 0. So in this case, just choose \(N\) such that when \(k \geq N\), the length of interval \(I_k\) is less than \(\epsilon\). Even though we chose the intervals to have length less than \(\epsilon\), we still have \(a_{n_k} \in I_k\) by construction and we still have \(x \in I_k\) by the Nested Interval Property. But since the interval length is less than \(\epsilon\), then the distance between \(a_{n_k}\) and \(x\) must be less than \(\epsilon\) or in other words \(|a_{n_k} - x| \leq \epsilon\) as wanted to show. Therefore, \((a_{n_k}) \rightarrow x\). \(\blacksquare\)

References: