Discussion

This result depends on the axiom of completeness (recall that MCT depends on it) and it’s another way of showing that \(\mathbb{R}\) is complete and has no holes because even if we have an infinite number of these nested intervals, their intersection will not be empty. Why another result? Because it might be more intuitive think about a never ending nested intervals without ever being empty than thinking about always having a least upper bound for bounded sets.

Proof (Introduction by Real Analysis by William Wade)

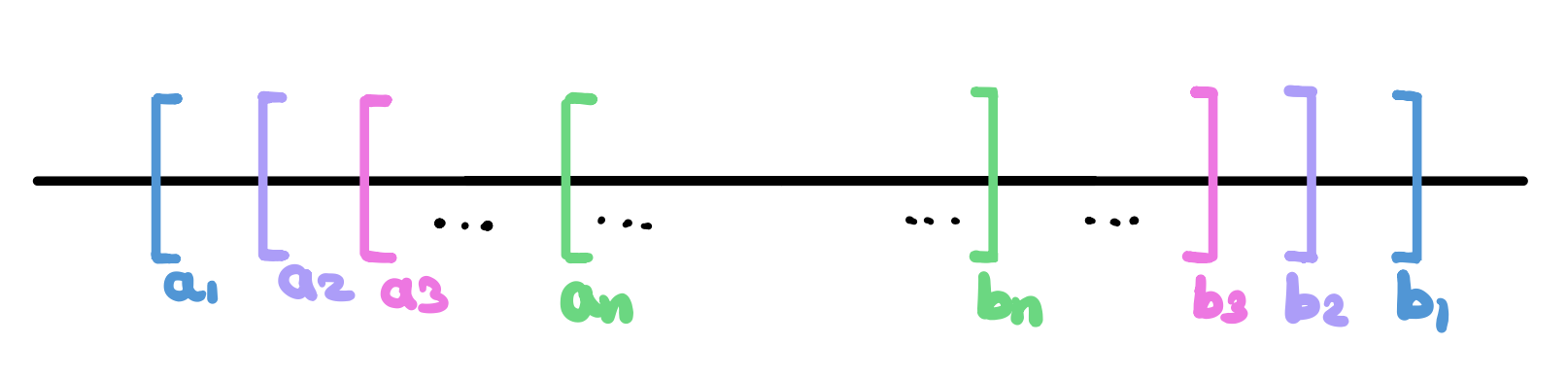

Consider the sequence \((a_n)\) of all left end points of each interval. This sequence is increasing and bounded above by \(b_1\). Therefore, by the Monotone Convergence Theorem, the limit exists and it is equal to the supremum of \((a_n)\). Similarly, consider the sequence \((b_n)\) of all right end points of each interval. This sequence is decreasing and bounded below by \(a_1\). Therefore, by the Monotone Convergence Theorem, the limit exists and it is equal to the infimum of \((b_n)\). Now, let

But we also know that \(a_n \leq b_n\) for all \(n \in \mathbb{N}\). Then by the Comparison Theorem, we know that \(a \leq b\). But this implies that

Hence, the intersection

Moreover, we are given that the length of the interval \(I_n = b_n - a_n \to 0\) as \(n \to \infty\). Then

Therefore, the intersection contains a single point as desired. \(\ \blacksquare\)

References

- Introduction to Analysis, An, 4th edition by William Wade

- Lecture Notes by Professor Chun Kit Lai