Proposition 12: To a given infinite straight line, from a given point which is not on it, to draw a perpendicular straight line.

Proof.

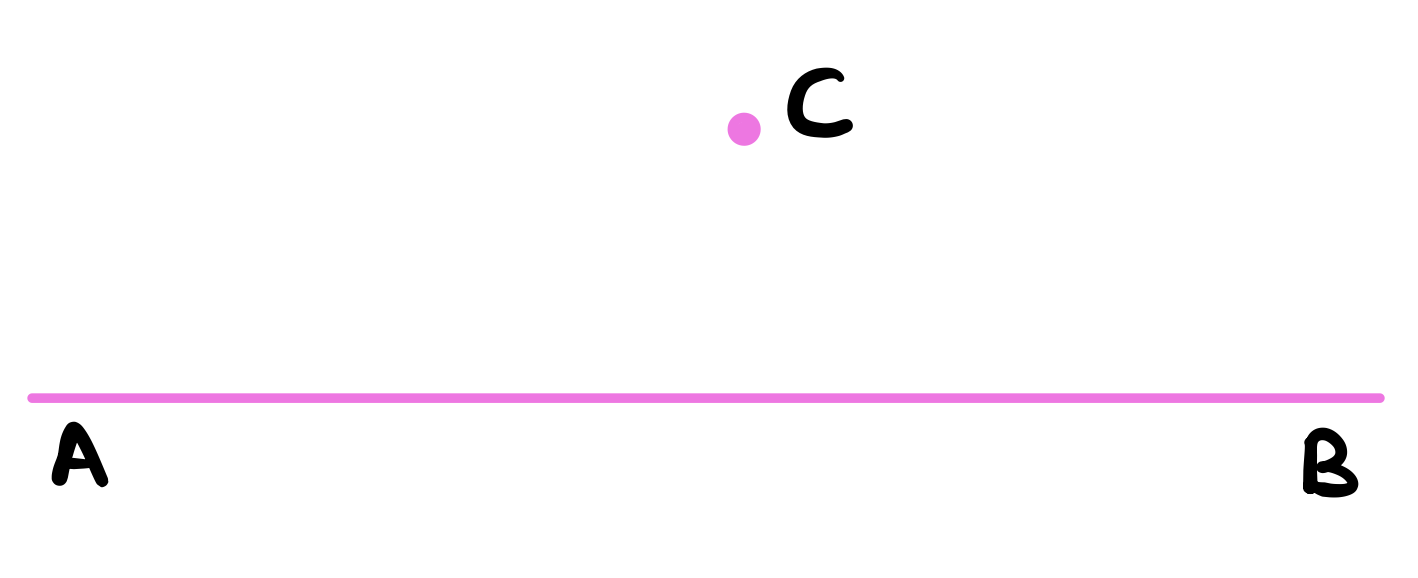

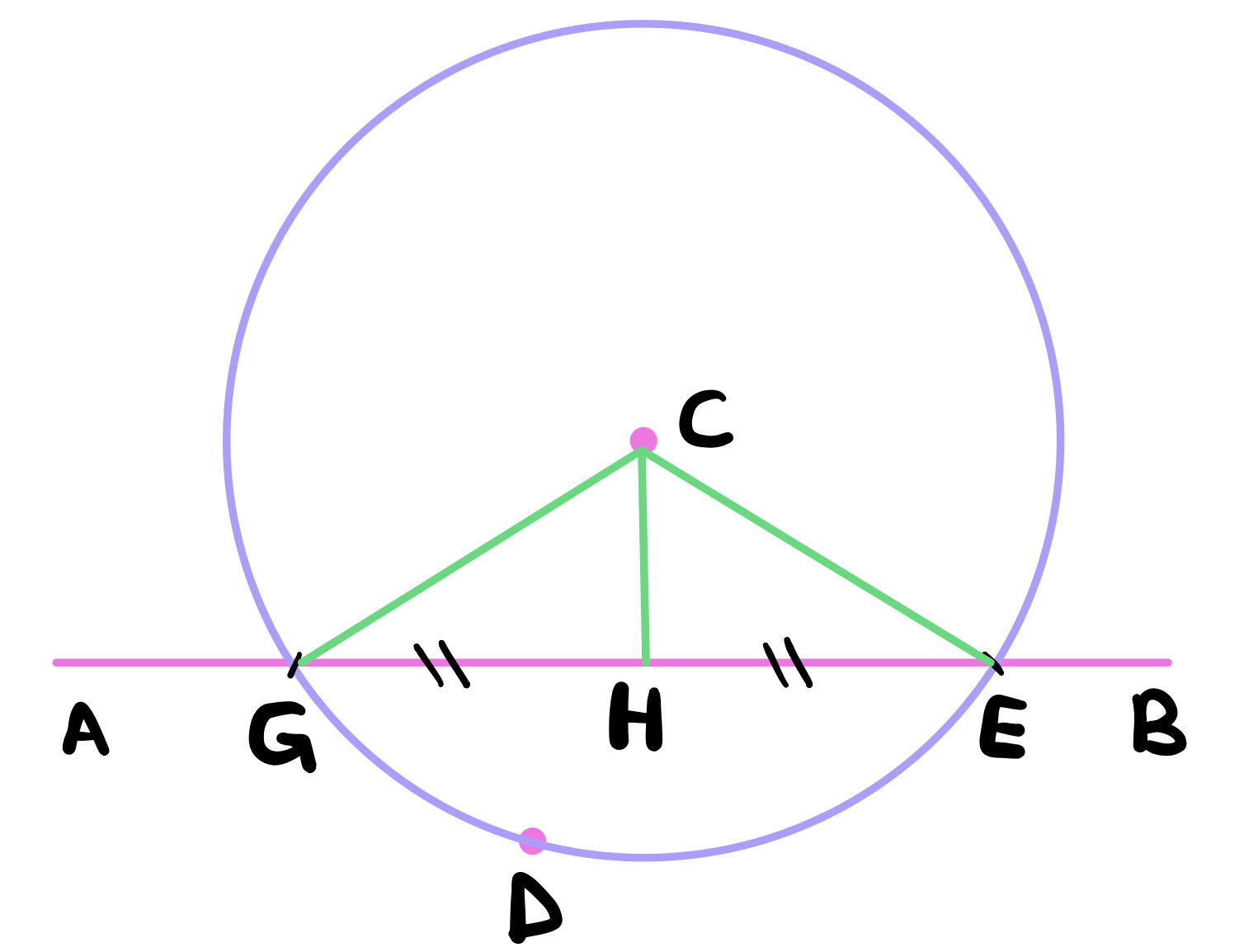

Let \(AB\) be the given infinite straight line and \(C\) the given point that is not on it. \(C\) will be on either side of the line but not on it since the line is infinite.

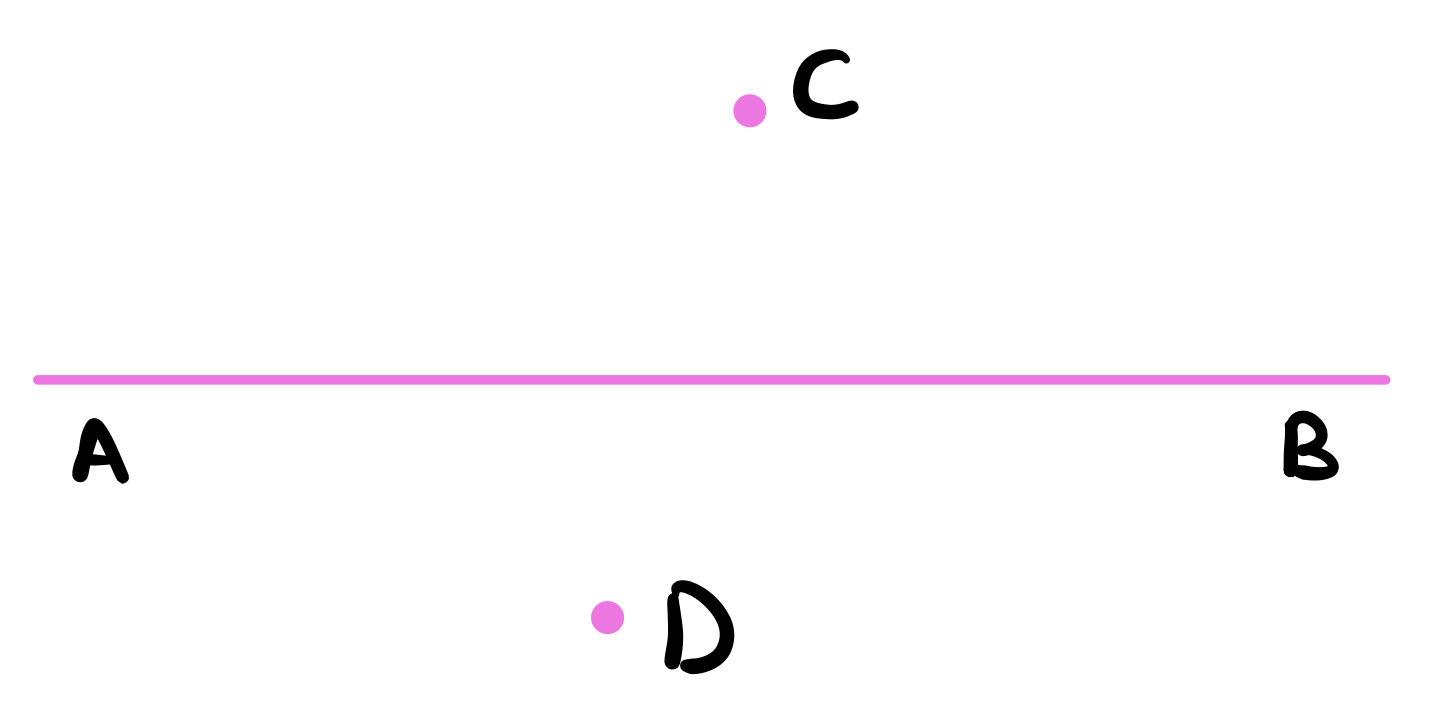

Let a point \(D\) be taken at random on the other side of the line.

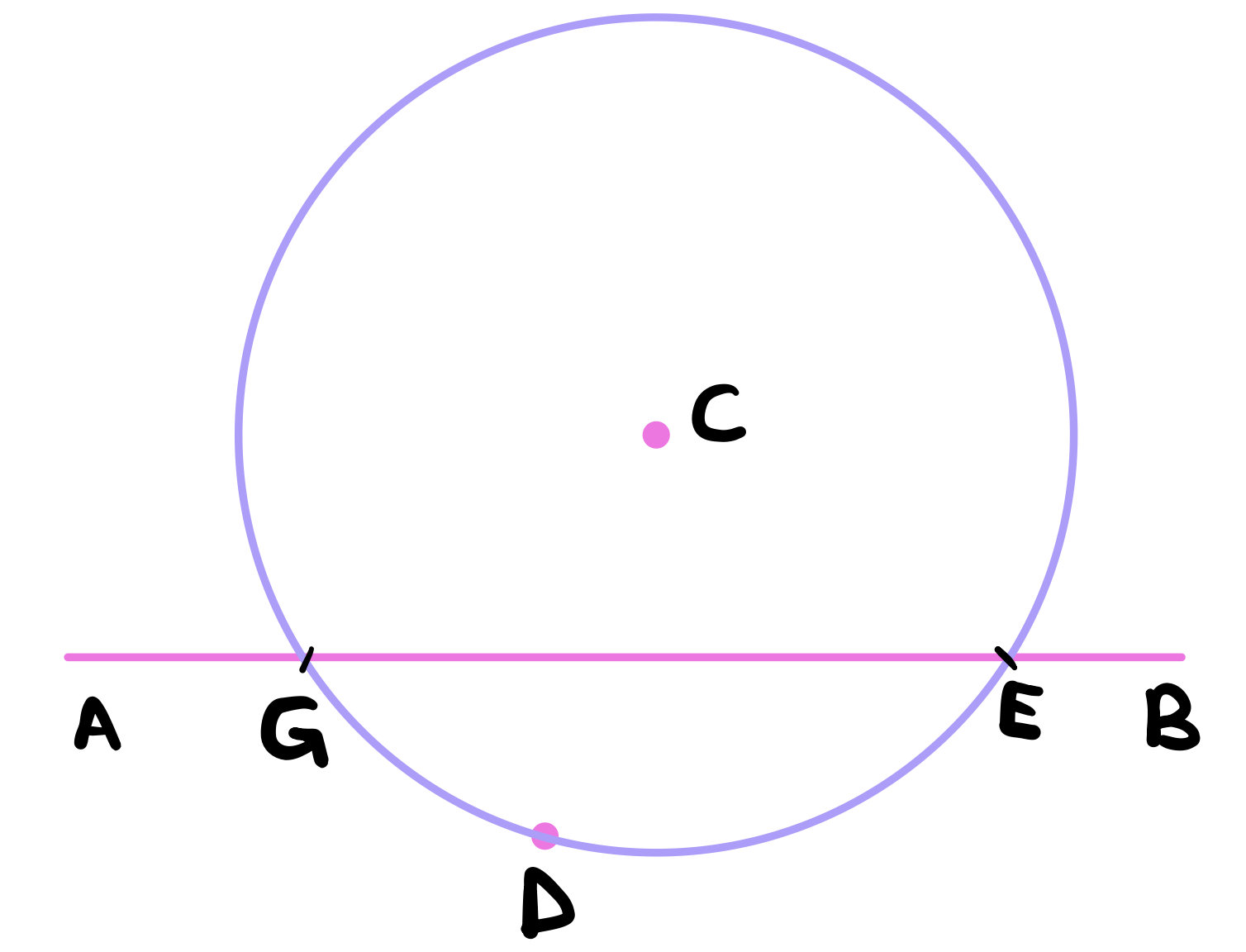

Using postulate 3, describe a circle with center \(C\) and radius \(CD\). Let the intersection points of the circle with the line \(AB\) be \(G\) and \(E\).

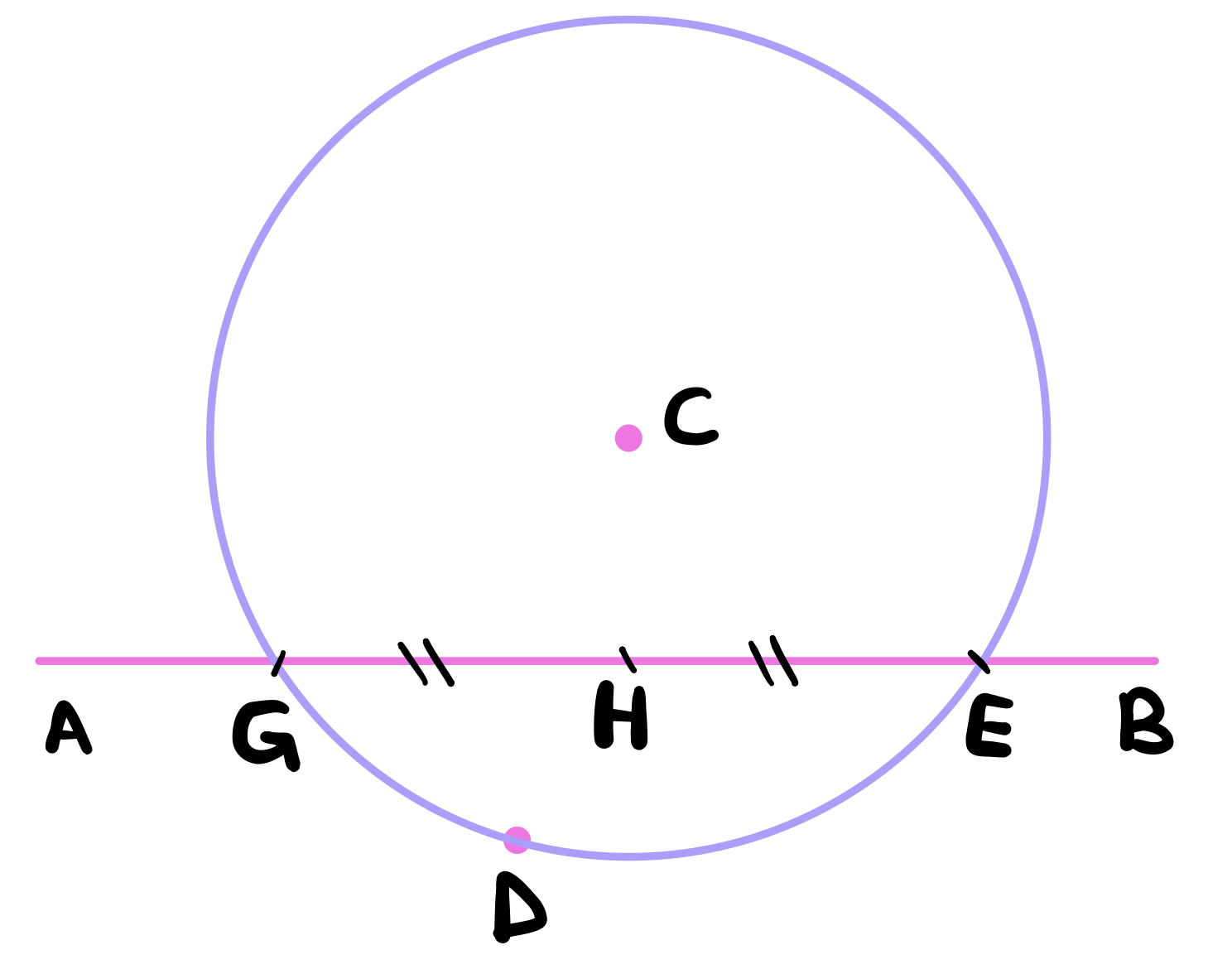

Use proposition 10 to bisect the line \(GE\) at \(H\).

Draw a line between points \(C\) and \(H\) using postulate 1. Similarly draw lines between \(C\) and \(G\), and again between \(C\) and \(E\).

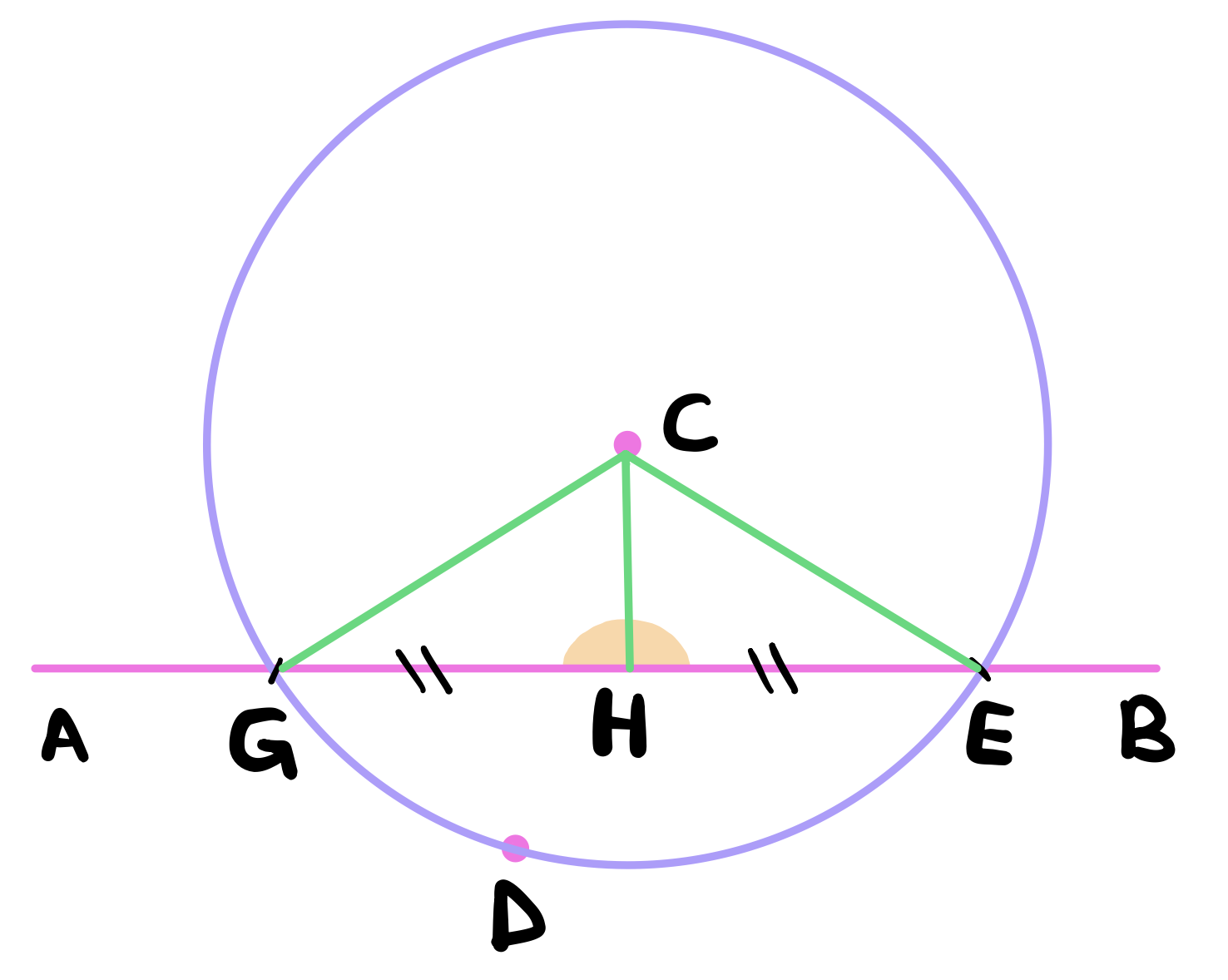

We claim that \(CH\) has been drawn perpendicular to the line \(AB\). To see this, notice that in the triangles \(CGH\) and \(CHE\), \(CG = CE\) by definition 15, \(CH\) is common to both triangles and \(HG = HE\) by construction. Therefore, we can conclude by proposition 8 that the angles \(\angle CHG\) and \(\angle CHE\) are equal.

But when a straight line is set up on another straight line makes the adjacent angles equal, then each of the equal angles is right and the straight line standing on the other straight line is called a perpendicular to that on which it stands (definition 10). Therefore, we can conclude that \(CH\) has been drawn perpendicular to the given infinite line \(AB\) from the given point \(C\) as required.

Thoughts:

(1) I think I know why the line needs to be infinite. This is because if it was finite then C could be on a line that is parallel to AB. In this case, we will not be able to construct a perpendicular line from C to AB. So I think Euclid just avoided this problem all together by making the line infinite.

(2) When they said the other side of the line, does this mean that D needs to be on the side that C is not on? Is this required for the proof to work?

References: