Given an array with \(n\) elements. We can find the minimum element or maximum element in \(O(n)\) time by doing a linear scan and keeping track of the minimum and maximum elements seen so far. What if we want to find the median element or the \(k\)th smallest element in general? One approach could be to sort the array in \(O(n\log(n))\) time and extracting the \(k\)th smallest element in \(O(1)\) time. Is there a faster way? Fortunately, yes! Quickselect is a randomized algorithm that can find the \(k\)th smallest element in just \(O(n)\) expected time. Moreover, with some smart modification to how we select the pivot, we can achieve a worst-case running time of only \(O(n)\) time.

Given an array with \(n\) elements. We can find the minimum element or maximum element in \(O(n)\) time by doing a linear scan and keeping track of the minimum and maximum elements seen so far. What if we want to find the median element or the \(k\)th smallest element in general? One approach could be to sort the array in \(O(n\log(n))\) time and extracting the \(k\)th smallest element in \(O(1)\) time. Is there a faster way? Fortunately, yes! Quickselect is a randomized algorithm that can find the \(k\)th smallest element in just \(O(n)\) expected time. Moreover, with some smart modification to how we select the pivot, we can achieve a worst-case running time of only \(O(n)\) time.

Algorithm

Quickselect turns out to be just a slight modification on quicksort which is described here! As a reminder, in quicksort, we start by picking a random pivot,

and then we partition the array around the pivot (in this case, 2).

We then repeat the same process of picking a pivot in each half and then partitioning around the pivots until the array is sorted. However, in quickselect, we’re only interested in finding the \(k\)th smallest element! The \(k\)th smallest element can only exist in either the left or the right half. Therefore, we can just search the appropriate half and simply throw away the other half. So, what can the pivot tell us about which half to search?

Suppose we’re interested in finding the 2nd smallest element which is 2 in the example above. Naturally, the pivot divides the array into two halves. The left half is less than the pivot and the right half is greater than the pivot. If we let the size of the left array be \(L\), then the pivot is the \(L+1\)th smallest element. Therefore, we can check if \(k == L+1\) to determine if the pivot itself is the \(k\)th smallest element. In the above example, \(k = 2\) and \(L + 1 = 2\) and we conclude the search and return the pivot.

Suppose instead we were searching for the smallest element in the array, \(k = 1\). We know from earlier that the pivot is the \(L+1\)th smallest element. Since \(k < L+1\), this means that the \(k\)th smallest element is in the left half. So, we call quickselect again on the left half.

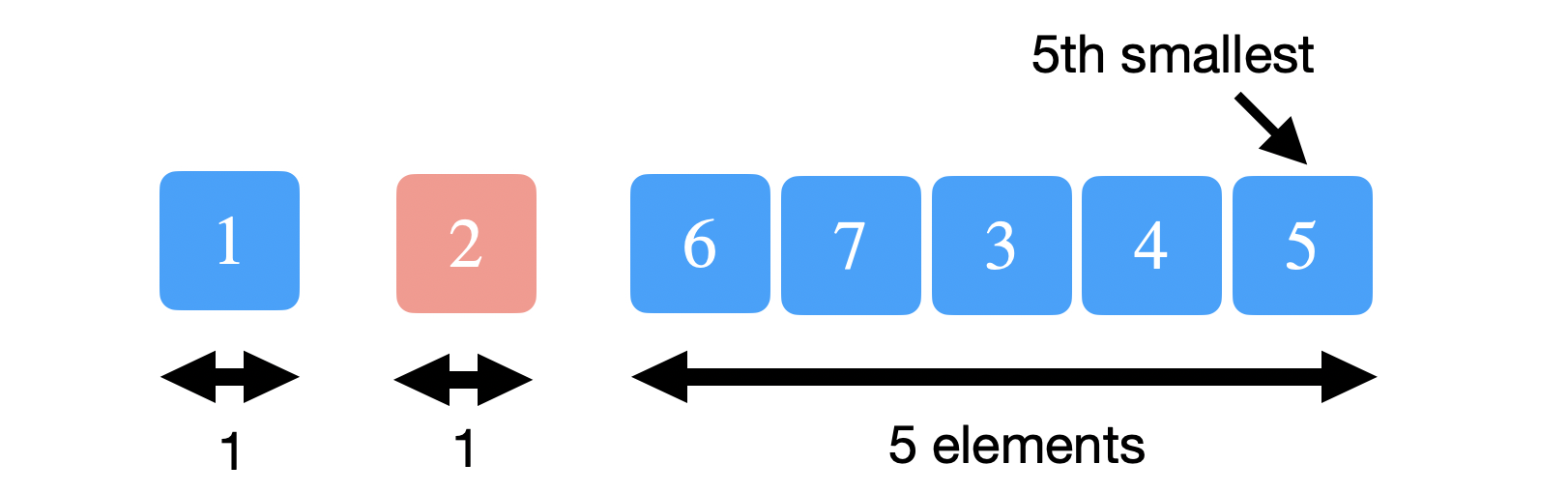

Finally, suppose we’re looking for the 5th smallest element, \(k = 5\). This time \(k > L+1\) and so we must search the right half. Do you search for the \(k\)th smallest element in the right half? No. Since we’re eliminating both the left array and the pivot, then our new search must look for the \(k-(L+1) = (k-L-1)\)th smallest element in the right half instead.

To summarize, there are three cases:

- If \(k\) is equal to \(L + 1\), then we’re done and we return the pivot.

- If \(k\) is less than \(L + 1\), then we call quickselect on the left half, searching for the \(k\)th smallest element.

- If \(k\) was greater than \(L+1\), then we call quickselect on the right half, but this time searching for the \((k - L - 1)\) smallest element.

Implementation

The following is an in-place implementation of quickselect.

int quickselect(std::vector<int>& a, int first, int last, int k) {

// if we only have 3 elements, just sort

if (last - first < 4) {

std::partial_sort(a.begin()+first, a.begin()+last, a.end());

return a[first+k-1];

}

// else, partition the array around a random pivot

int p = randomized_partition(a, first, last);

int left_length = p - first;

// we lucked out, we're exactly at the kth element

// remember that indexing start at 0 and so we want k-1

// also we return the kth element starting at position first and not 0

// so we have take that into account when we return the element

if (k-1 == left_length) {

return a[first+k-1];

}

// otherwise, we either search the left half or the right half

if (k-1 < left_length) {

return quickselect(a, first, p-1, k);

} else {

return quickselect(a, p+1, last, k-left_length-1);

}

}Correctness of Quickselect

TODO.

Here is a proof by strong induction: here

Worst case analysis

In the worst-case, we’re always choosing a pivot such that our kth element ends up in the larger half. Not only that, but our choice of pivot is always either the smallest or largest element and so in each iteration, the number of elements decrease by only one element. Therefore, we have the following recurrence,

Remember that the \(O(n)\) part is due to partition. This recurrence has the solution, \(T(n) = O(n^2)\).

Best case analysis

In the best-case, we’re always choosing a pivot that divides the array in the middle and so we have the following recurrence,

This recurrence has the solution, \(T(n) = O(n)\).

Expected case analysis

The expected running time of Quickselect turns out to be \(O(n)\).

Proof: TODO: (basically section 9.2 in CLRS (not easy though))

Can quickselect run in linear time in the worst case?

So far, we’ve seen that quickselect runs in \(O(n^2)\) in the worst case. Could we do something so that quickselect actually runs in linear time in the worst case? The answer is yes! we can modify the way we select the pivot to guarantee a linear runtime in the worst-case! (TODO: 9.3 in CLRS)

References

- CLRS Chapter 9

- CS161 Stanford