We’ve looked at how to check if two segments intersect in just \(O(1)\) time. Now, suppose we have a set of line segments and we want to know if any two segments in this set intersect. How can we do that?

We’ve looked at how to check if two segments intersect in just \(O(1)\) time. Now, suppose we have a set of line segments and we want to know if any two segments in this set intersect. How can we do that?

Sweep Line

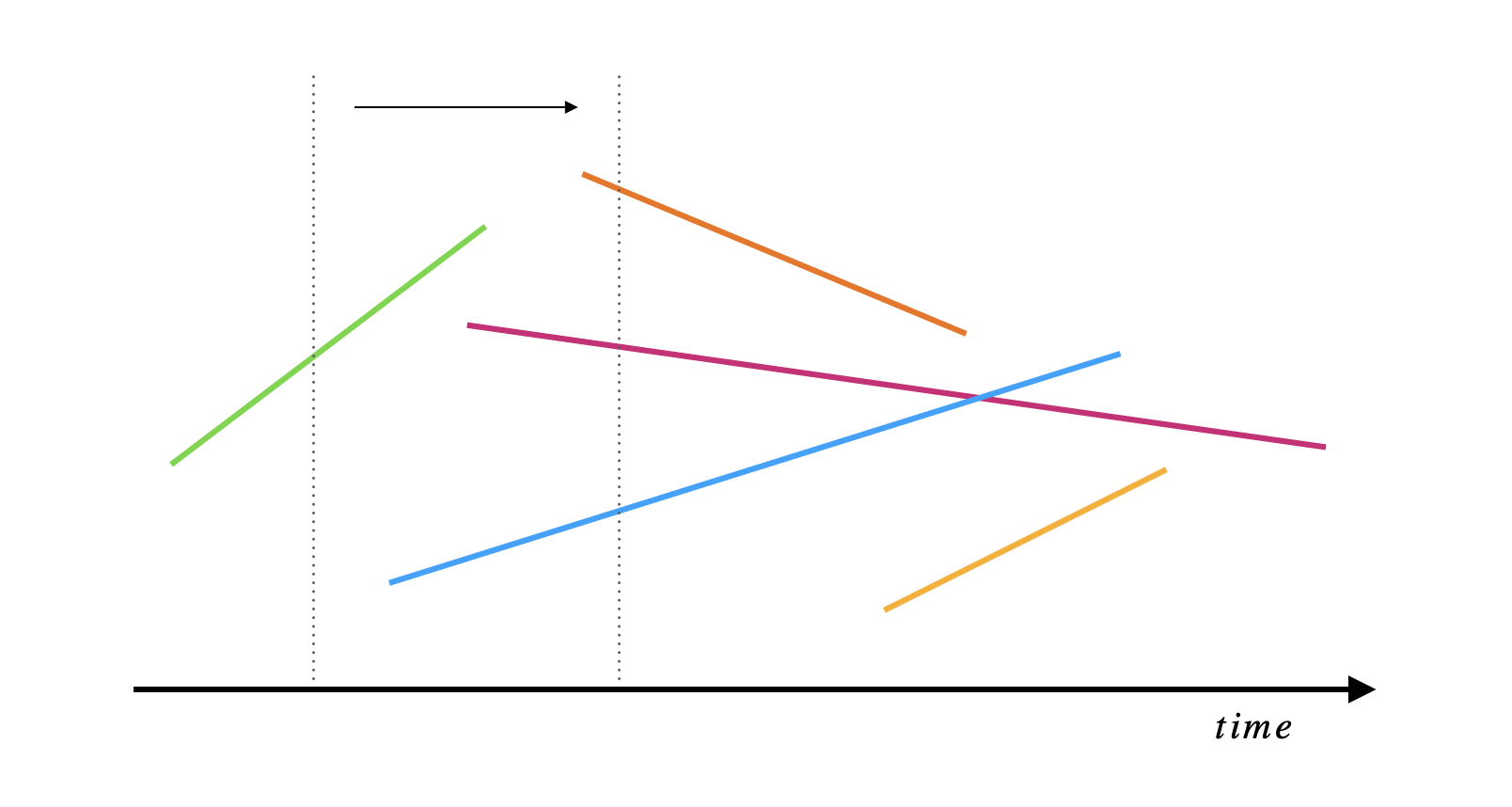

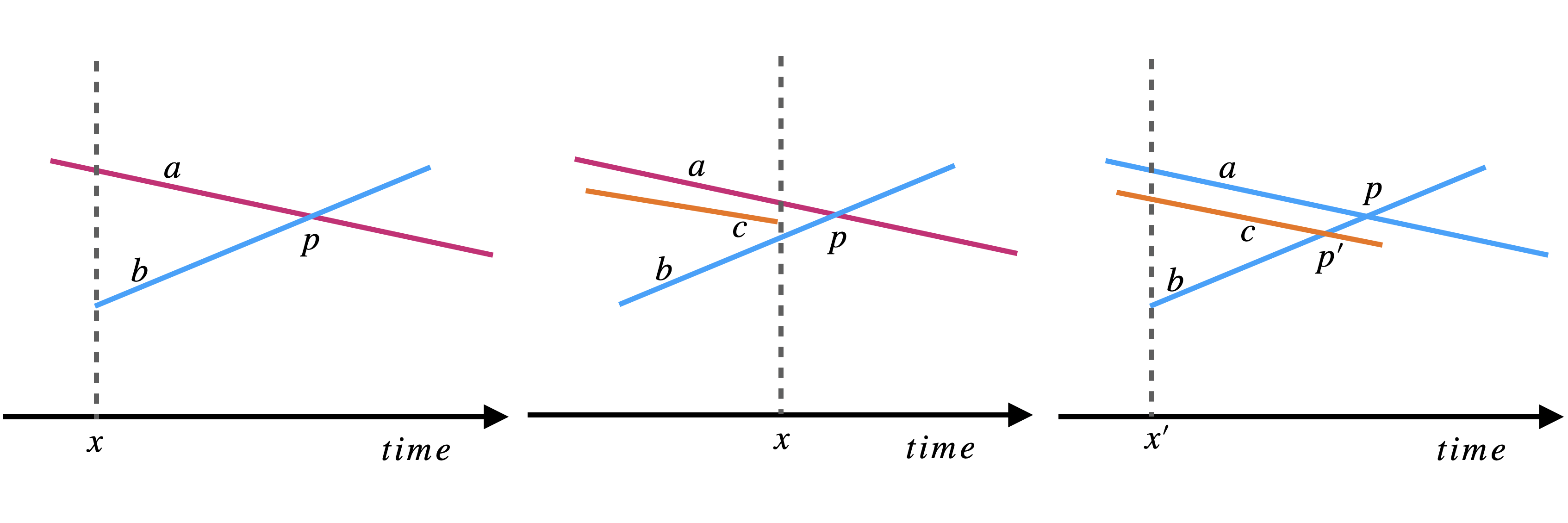

Sweep Line is a common technique used often in computational geometry where we imagine a vertical line going through the set of objects we’re interested in. The sweep line sweeps through one dimension that we chooses. This dimension is treated as a dimension of time. For example, in the figure above, the x-axis is our time line. The vertical line sweeps through the line segments to check whether any two segments intersect.

Sweep Line is a common technique used often in computational geometry where we imagine a vertical line going through the set of objects we’re interested in. The sweep line sweeps through one dimension that we chooses. This dimension is treated as a dimension of time. For example, in the figure above, the x-axis is our time line. The vertical line sweeps through the line segments to check whether any two segments intersect.

Basics

First, we’ll assume that no three points intersect at a single point and that we don’t have vertical line segments. Second, instead of talking about line segments, we’ll just talk about the individual points that make up these segments. We’ll label the start point of a segment with “s” and the end point of a segment with “e”. If we have \(n\) segments, we will have \(2n\) points. Finally, we’ll sort these points by their x-coordinate. In case of ties, we’ll place the “start” points before the “end” points. If we still have ties, we’ll put the points with the lower y-coordinate first. Our dimension of time here is the x-coordinate and we will sweep from left to right.

Big Idea

Naively, we would spend \(O(n^2)\) time to check if any pair intersects by literally checking all possible intersections. CLRS presents a very smart algorithm that is based on one big idea.

Naively, we would spend \(O(n^2)\) time to check if any pair intersects by literally checking all possible intersections. CLRS presents a very smart algorithm that is based on one big idea.

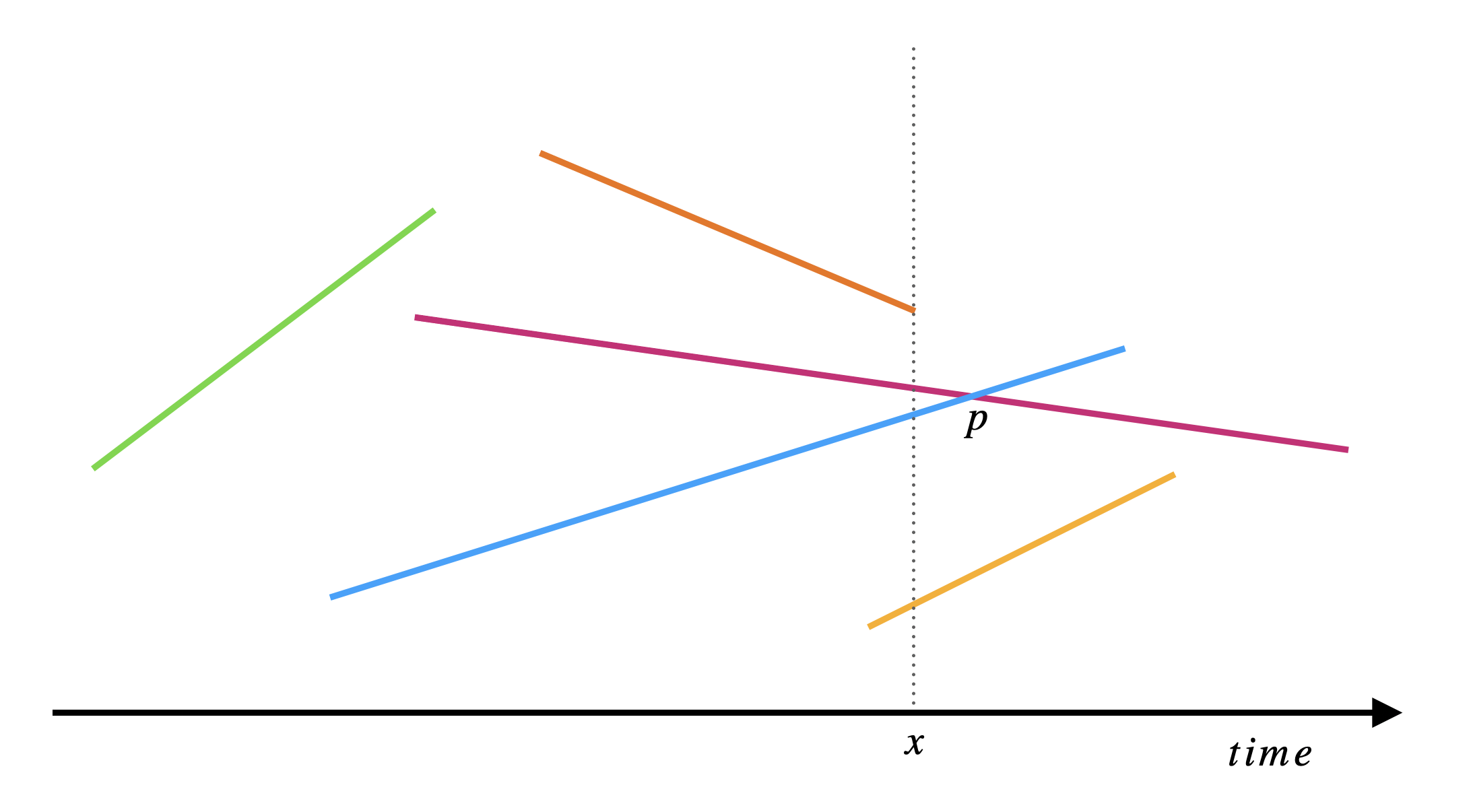

Sort the segment points and sweep through the points from left to right, stopping to evaluate the sweep line at every segment point. Suppose we know that a pair of segments intersect. The big idea is that we are guaranteed to have the two line segments be consecutive at some sweep line. In the figure above, the line segments intersect at \(p\) and they are consecutive at the sweep line \(x\). This is a huge idea! why? Because now we can just sweep through the points from left to right. When we evaluate a point, we only need to check the segment right below it or the segment right above it for a possible intersection! This means that the running time is dominated by the sort which runs in \(O(n\log(n))\).

Proof

If we have two segments \(a\) and \(b\) intersecting at some point \(p\). Why must the segments be consecutive at some sweep line?

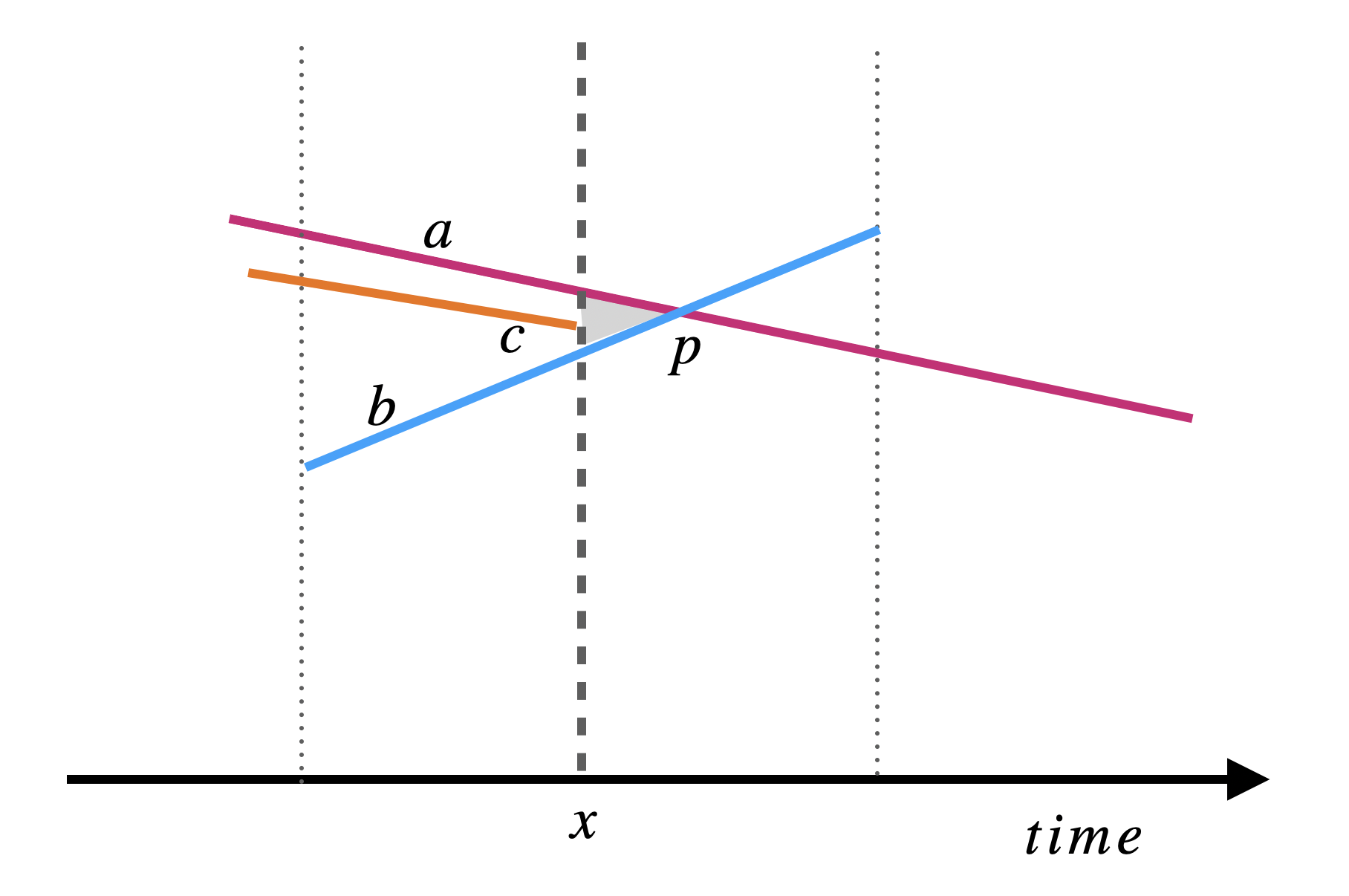

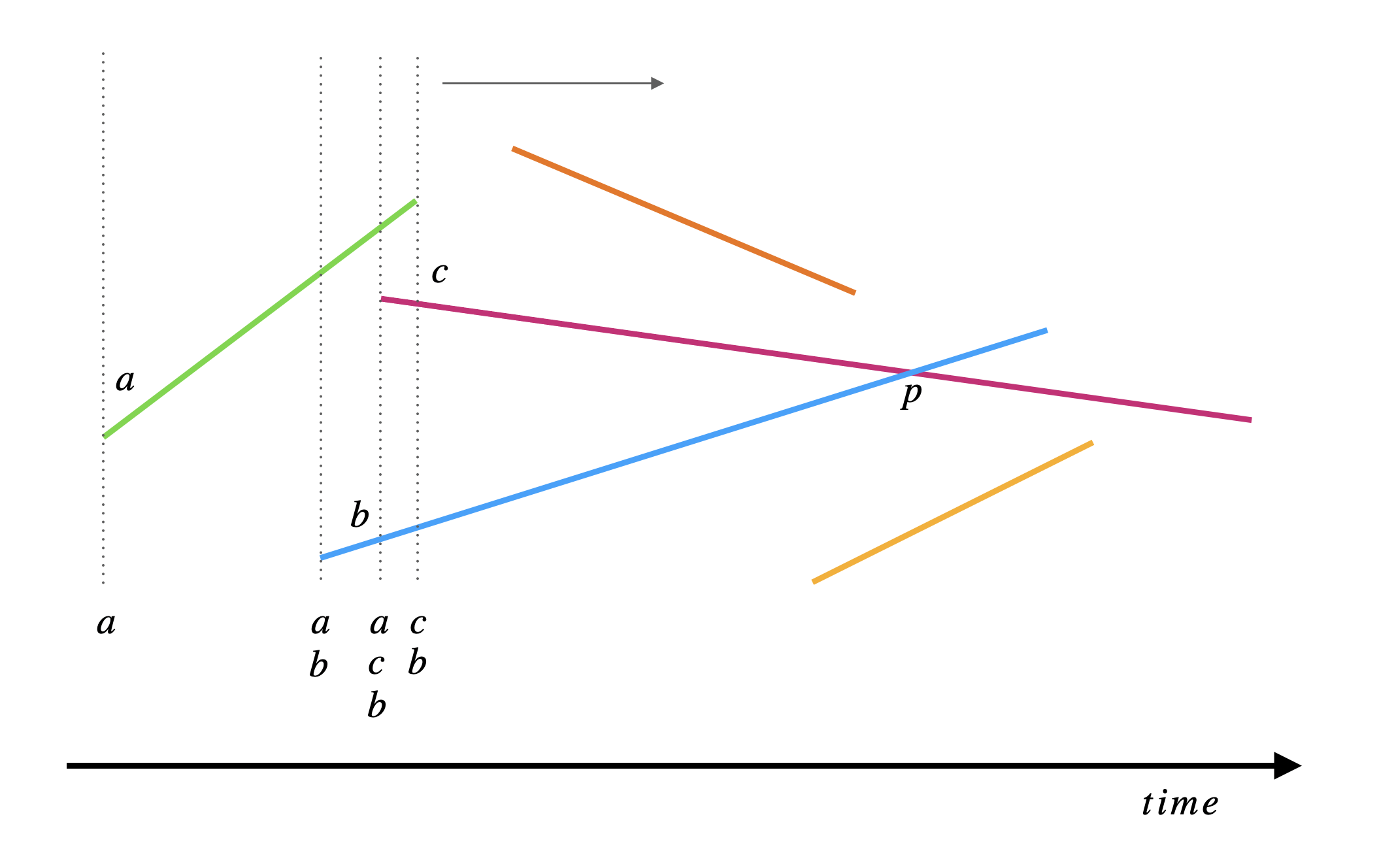

Suppose we are at some sweep line \(x\), let \(T\) be the set of segments intersecting \(x\). Let \(\succeq_x\) be a relation on \(T\). We say \(a \succeq_x b\) if both \(a\) and \(b\) intersect \(x\) and the intersection of \(a\) with \(x\) is higher than the intersection of \(b\) with \(x\). The below figure shows segments \(a\), \(b\) and \(c\) intersecting sweep line \(x\).

\(\succeq_x\) is total preorder. This is because for any two segments \(a, b \in T\), either \(a \succeq_x b\) or \(b \succeq_x a\) or both and so \(\succeq_x\) is a total order. Furthermore, if we have a third segment \(c \in T\) such that \(a \succeq_x c\) and \(c \succeq_x b\) then we must have \(a \succeq_x b\) and so \(\succeq_x\) is transitive.

When we pass the intersection point \(p\), the segments \(a\) and \(b\) reverse their order in the total preorder. Before the intersection, we had \(a \succeq b\) and after the intersection, we have \(b \succeq a\). Furthermore, since no three lines intersect at the same point then we must have some sweep \(x\) where \(a\) and \(b\) are consecutive. We basically want to prove there is some empty triangle bounded by \(a, b\) and \(x\) which will imply that \(a\) and \(b\) are consecutive in the total preorder \(\succeq_x\).

Proof: Suppose the triangle isn’t empty and pick the right most intersection point with the triangle to the left of \(p\), call it \(q\). We know \(p != q\) because of the assumption that we don’t have three segments intersecting at the same point. We know the \(x\)-coordinate of \(q\) is less than \(p\) by assumption. We can construct an empty triangle defined by the the sweep line at \(q, a\) and \(b\). Therefore, \(a\) and \(b\) will be consecutive in the total preorder \(\succeq_x\). \(\blacksquare\)

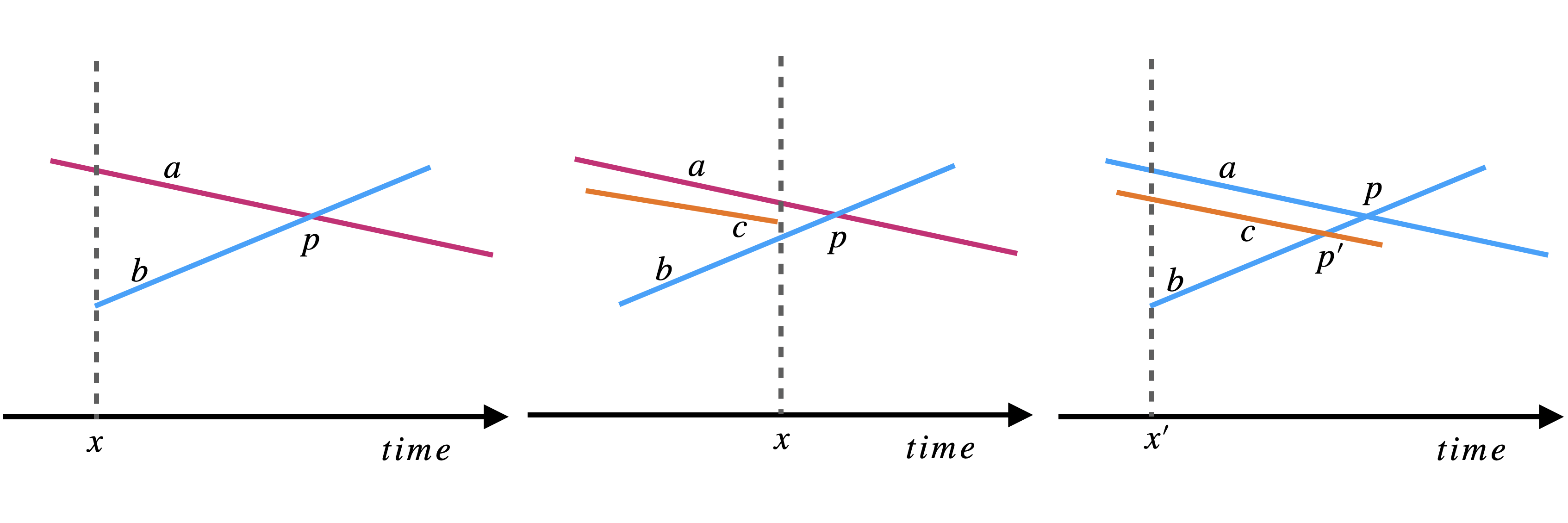

There is another more intuitive way to think about this. We have two cases. We either have no segment points besides \(a\) and \(b\) before we hit \(p\) which will imply that \(a\) and \(b\) are consecutive in the total preorder of the sweep line that hits the latest segment start of \(a\) and \(b\). (left case in the figure). Or we do have some segment \(c\) but because of the precondition that no three segments intersect at \(p\) then we must hit the end point of \(c\) before \(p\) and so \(a\) and \(b\) will be consecutive after that point (middle case). Someone might ask, what if we don’t hit the end point of \(c\) first and \(c\) continues? This is the third case in the figure which is just misleading, because in this case, we will discover \(p^{\prime}\) first instead and return true!

Algorithm

The algorithm will maintain two sets of data.

- The first set, \(S\), is the sorted list of start and end points, also called the event points.

- The second set is \(T\), the sweep-line status. \(T\) will hold the ordered segments currently intersecting the current sweep line.

The algorithm then iterates through the event-points or \(S\). There two cases only:

-

The point is a start point of some segment \(t\). We will add the segment to the sweep-line-status and then check if \(t\) intersects the segment below it or the segment above it. If the answer is yes, then we’re done. If not, we continue processing the next point.

-

The point is an end point of some segment “r”. We will check if the segments below \(r\) and above \(r\) intersect and, then we will remove \(r\) from the sweep-line-status.

Pseudocode

// S is a set of n segments

any_segments_intersect(S) {

// Assume or rearrange S to have 2n points (the start and end points of each segment)

// Sort the points in S by their x-coordinate, breaking ties by putting

// start points before end points and then lower y-coordinate first

T = set() // sweep-line-status

for (each point p in S) {

if (p is a start point of some segment e) {

insert(T, e)

if (there is a segment above e and it intersects e OR

or there is a segment below e and it intersects e) {

return true;

}

} else { // p is an end point

if (there is a segment above e and there is a segment below e AND

both of these segments intersect) {

return true;

}

Delete(T, e)

}

}

return false;

}

Proof

But why does any of the above work? Is this magic? kind of. To prove the correctness of the algorithm we need to prove

| any_segments_intersect(S) returns true if and only if there is an intersection among the segments in \(S\). |

Proof:

\((\Rightarrow)\): If any_segments_intersect returns true, then it is clear from the algorithm above that it can only return true if an intersection passes so we’re good.

\((\Leftarrow)\): If there is an intersection, we’ll prove that any_segments_intersect finds it. Suppose we have an intersection and let \(p\) be the left most intersection with the lowest y-coordinate. Let \(a\) and \(b\) be the intersecting segments. We know from the previous proof that no three segments can intersect at \(p\) and so \(a\) and \(b\) will be consecutive at some sweep line \(x\). We also know that there is some segment start or end point \(q\) that intersects \(x\). We have three cases:

-

Case 1: We already have either \(a\) or \(b\) in \(T\) and then we hit the start of \(a\) or \(b\) and so the first if-statement catches this.

-

Case 2: We hit the end point of some segment \(c\) and so the second if-statement catches this case. We compare \(a\) and \(b\) and delete \(c\).

-

Case 3: We didn’t process the sweep line \(x\) at \(q\) because we’ve already hit \(p'\) before! (this must be the case because \(c\) must either end before \(p\) hits \(a\) or \(b\) before \(p\) since we can’t have 3 points intersecting at \(p\))

Therefore, if there is an intersection point, then any_segments_intersect must return true. \(\blacksquare\).

Implementation

TODO

References

CLRS Chapter 33

Proof