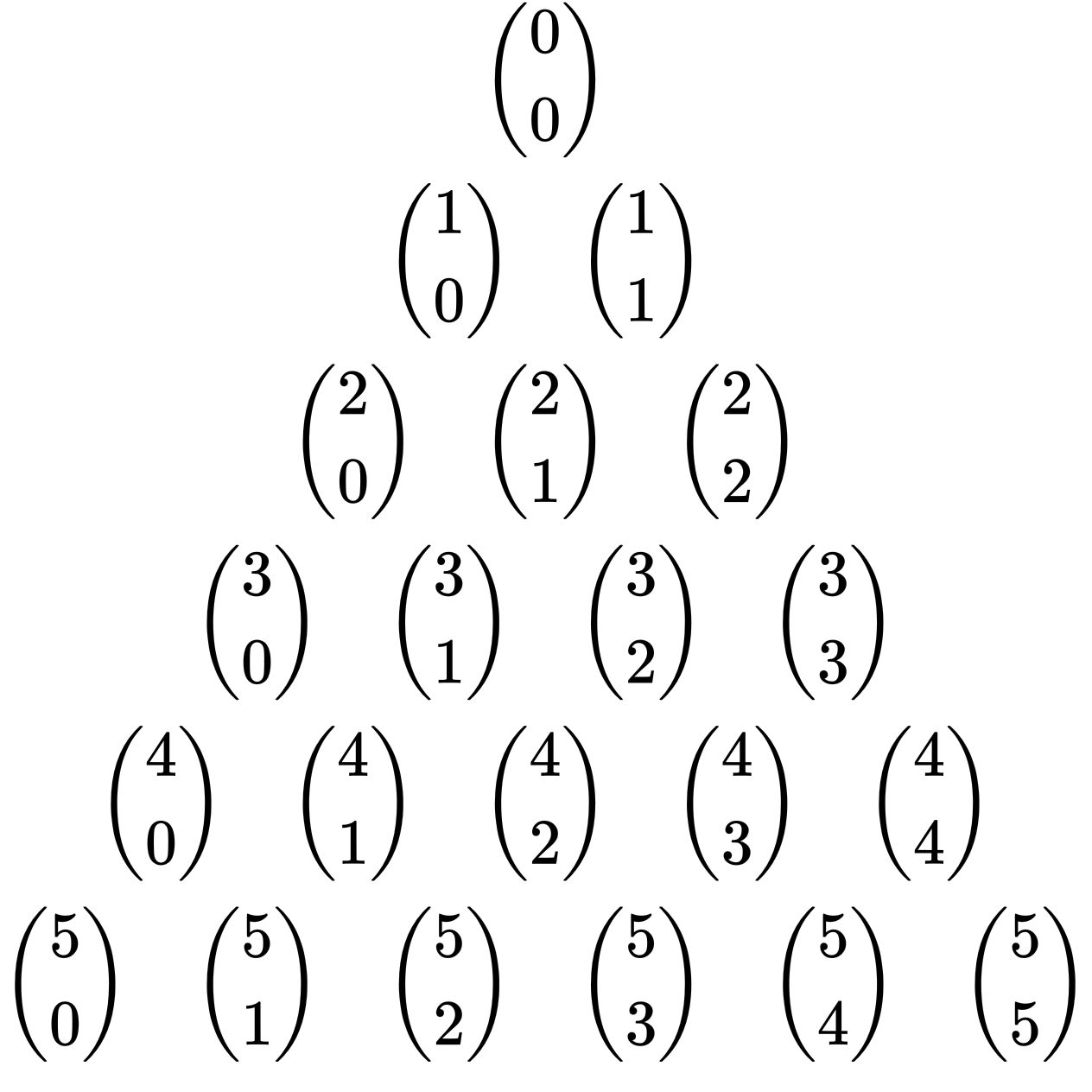

We start with the combinatorial definition as follows

Another way we see these binomial coefficients is when we expand a binomial (sum of two elements) as follows

We also have an explicit way (third way) to expand the binomial coefficient as follows

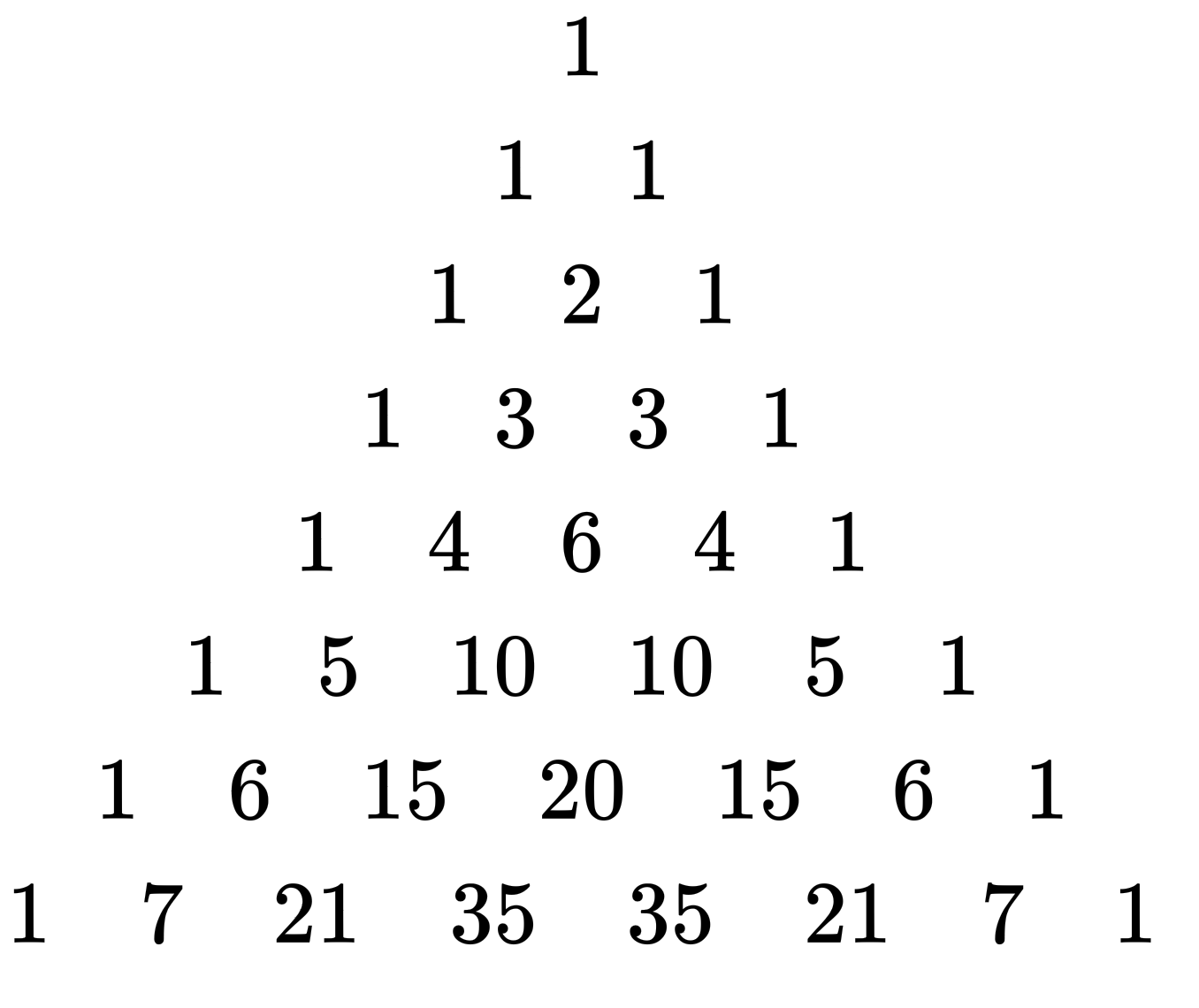

The fourth way to see these coefficients is by also drawing Pascal’s triangle below

All Definitions are Equivalent

What we want to do next to show that all these definitions are equivalent. To do this, we will show that all definitions are equivalent to the first combinatorial definition. So take the second definition where we saw that the binomial coefficients appear in the expansion of \((x+y)^n\). We will show that it’s equivalent to the combinatorial definition. So take for example \((x+y)^5\). Then

Suppose we want to know the coefficient of \(x^3y^2\). Then, this coefficient is equivalent to the number of ways to choose for examples 2 \(x\)’s from the set of 5 \(x\)’s above. This is also the same as the number of ways to choose the 3 \(y\)’s above.

Now, consider Pascal’s triangle. We can also show that it is equivalent to the combinatorial definition. (TODO) Finally, we need to show the explicit definition is the same as the combinatorial definition. (TODO). (Please watch the lecture)

Binomial Polynomials

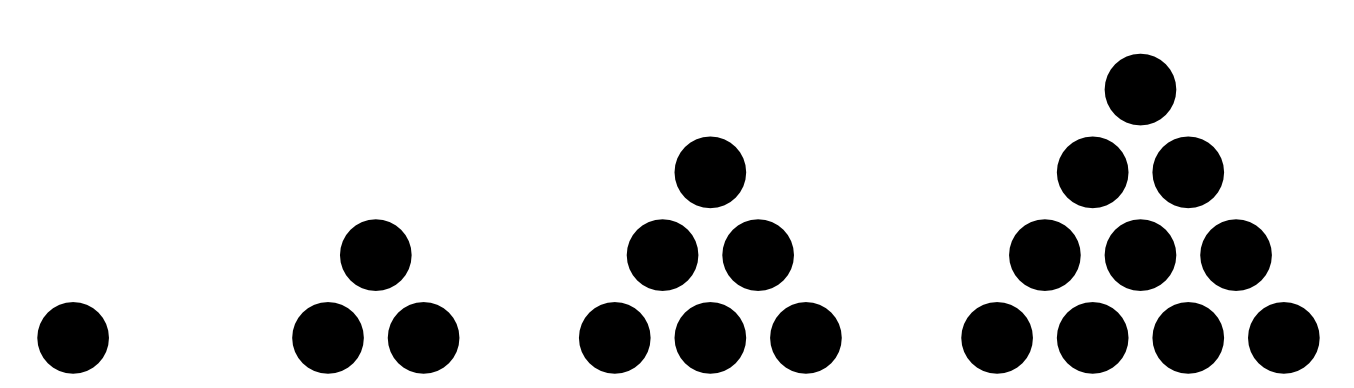

Consider the left edges of Pasal’s triangles.

The first two left edges is uninteresting. Now consider the third left edge

These are the triangular numbers.

They have the same properties as the binomial coefficients. For example, consider the 4th triangular number. We we’re adding 4 new dots to the last row of the third triangle. The third triangle has 6 dots originally and we’re adding 4 new dots. If you look at Pascal’s triangle again, you will see that \(10 = 6 + 4\). So we can figure out the next triangular number by using these binomial coefficients or Pascal’s triangle. Next, consider the next left edge. These are called the tetrahedron numbers

They represent the number of the ways to fill a tetrahedron with marbles. In fact, these left edges as we know are just the binomial coefficients and we can also write them as

Each left edge gives us \(\binom{n}{k}\) for \(n = 0,1,2,3,4\).

Binomial polynomials on the other hand are the polynomials that map \(n\) to \(\binom{n}{k}\) for a chosen value of \(k\). For example

Even though these polynomials have fractional coefficients, we know these values are integers because they are binomial coefficients. So let’s look at the values of \(n\) for different polynomials and contrast these with the binomial coefficients

| \(n\) | \(n^0\) | \(n^1\) | \(n^2\) | \(n^3\) | \(\binom{n}{0}\) | \(\binom{n}{1}\) | \(\binom{n}{2}\) | \(\binom{n}{3}\) | |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 27 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

Observe the difference in the values between taking powers of \(n\) versus the values of the binomial polynomials for different \(n\) values as shown in the shaded regions above. The binomial values are extremely simple. This gives a very useful application. Suppose now we write a polynomial in terms of the binomials above.

If \(n\) is integer, this value is always integer. This is not true for other polynomials.

More Properties of Binomial Coefficients

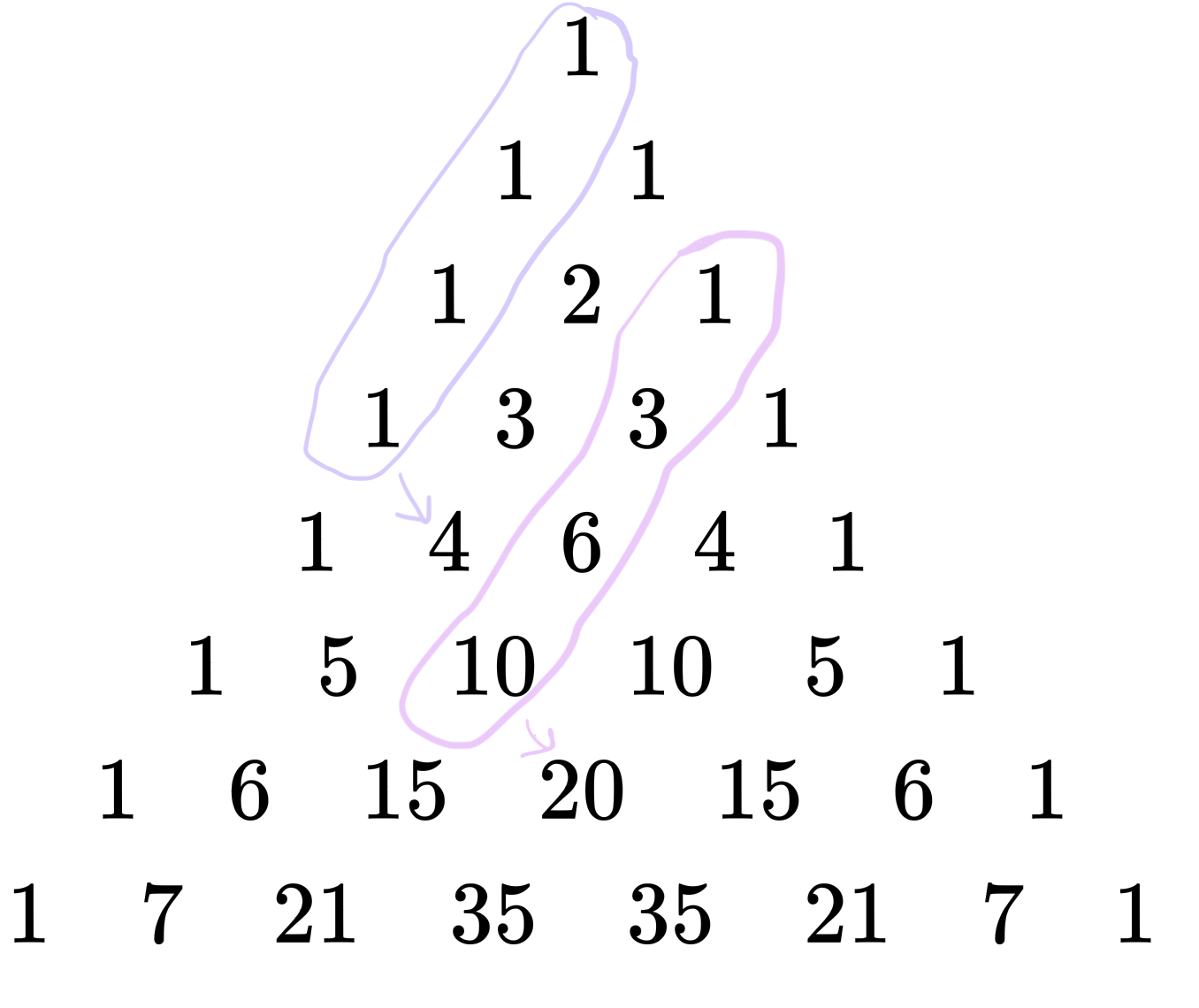

Looking at Pascal’s Triangle again.

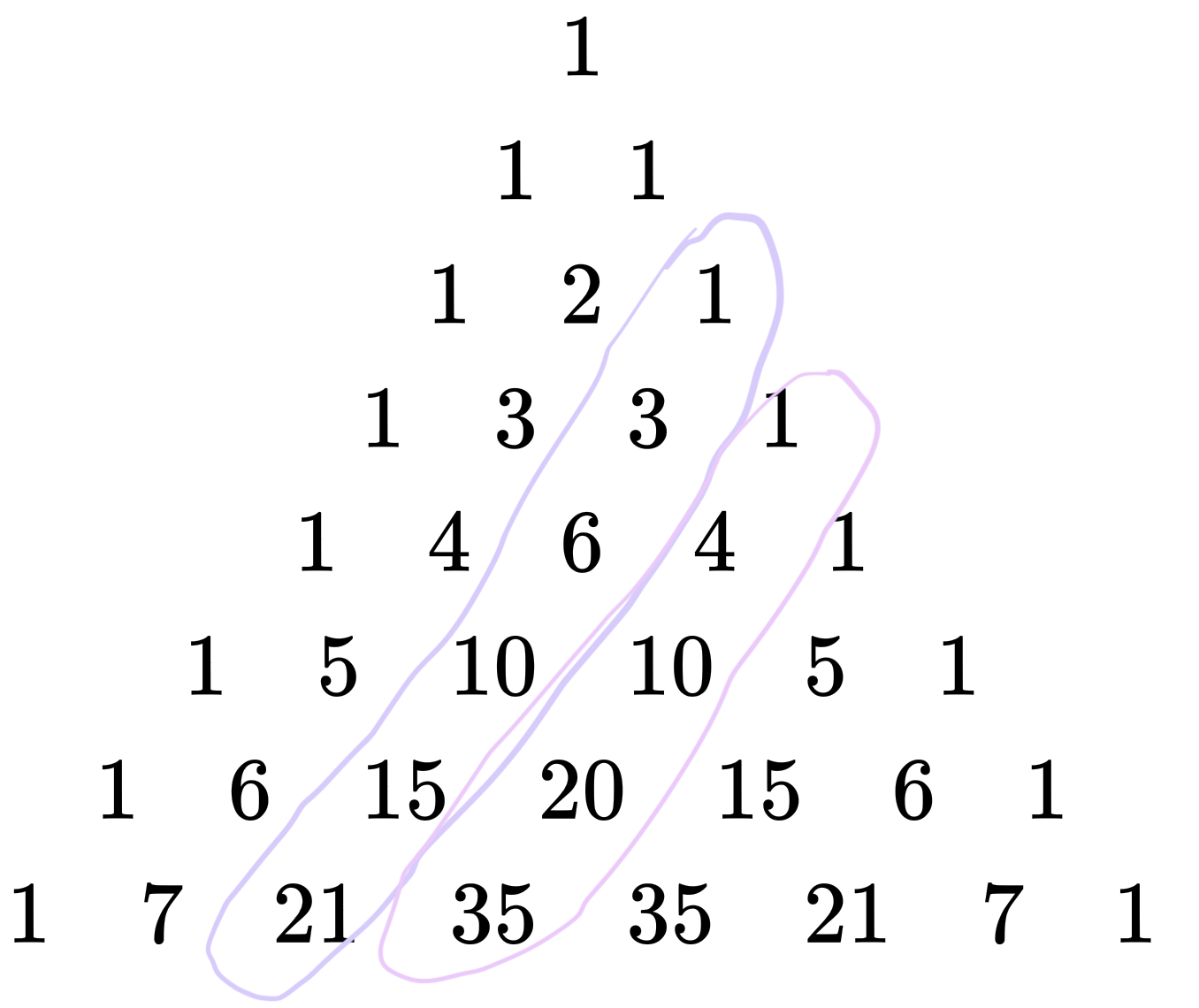

We also see that each number is the sum of all the numbers in the left edge above it. So if you take 4, then it’s the sum of \(1 + 1 + 1 + 1\) in the left edge above it. If you take \(20\), it’s the sum of \(1 + 3 + 6 + 10\) and so on. This is fact a property of binomial coefficients and we can write it as follows

Another property is that choosing \(k\) elements from a set is the same as the complement

Another property is that if you sum all the rows in Pascal’s triangles, we get the sequence \(1 \ \ 2 \ \ 4 \ \ 8 \ \ 9 \cdots\) which is exactly \(2^n\). We prove this using many ways. One way is to use the combinatorial definition and to notice that \(\binom{n}{0} + \binom{0}{1} + \cdots + \binom{n}{n}\) is equal to the number of ways to select a 0-element subset from a set of \(n\) elements plus the number of ways to select a 1-element subset plus the numer of ways to select a 2-element subset and so on. But this is just the number of all subsets we can form from a set of \(n\) elements.

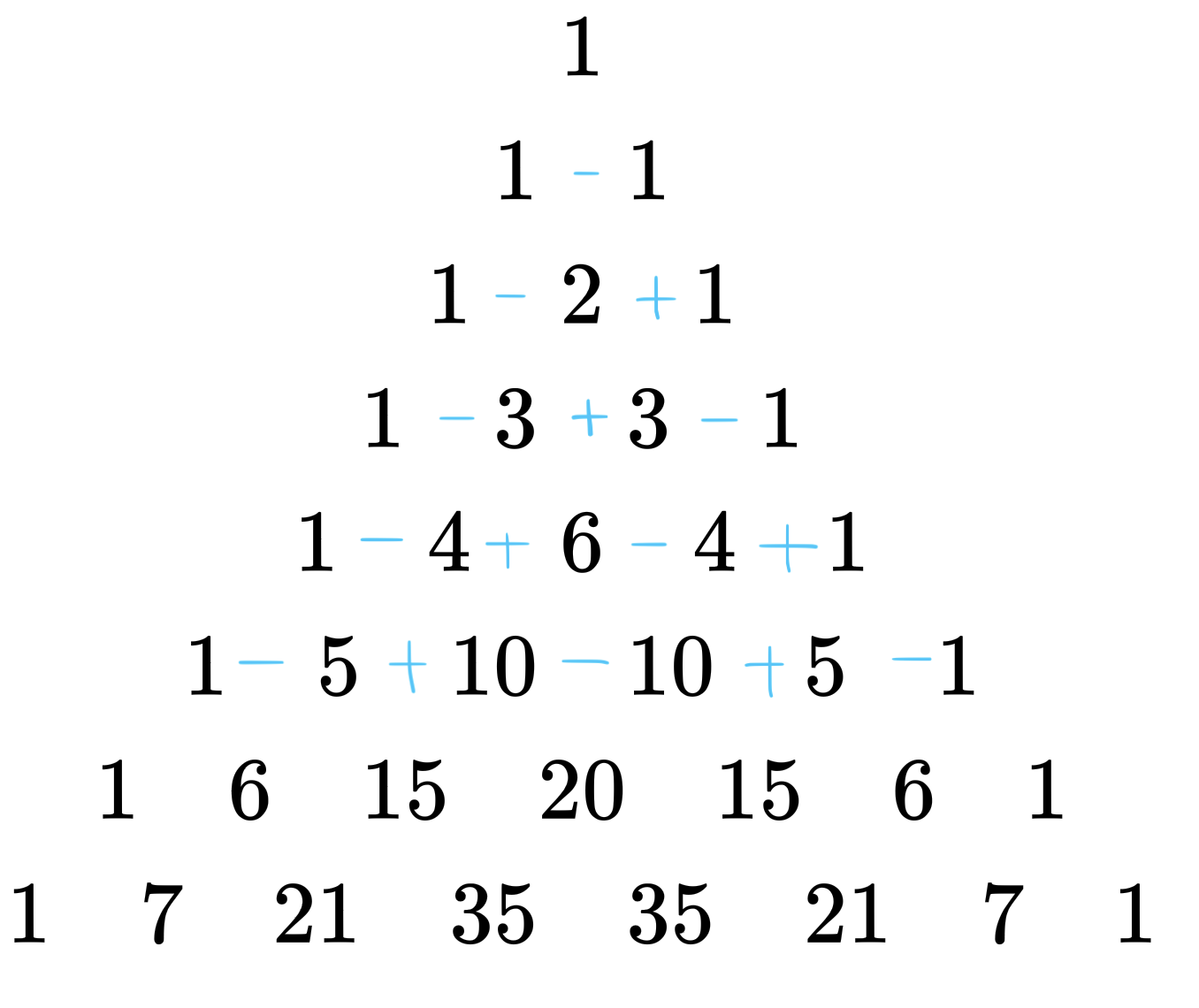

Now, consider taking the alternating sums of each row in Pascal’s triangle

We will notice that the sums are \(1 \ \ 0 \ \ 0 \ \ 0 \ \ 0 \ \ 0 \cdots\). Why is that? We can use a generating function argument where we set \(y = -1\) in \((x+y)^n\). But we can also use a combinatorial definition argument. To see this, We claim that given a set of size \(n \geq 1\), the number of even element subsets is equal to the the number of odd element subsets. The alternating sum in each row is the number of even element subsets minus the number of odd element numbers. To see, fix an element \(i\). Now any subset formed either contains \(i\) or doesn’t contain \(i\). One subset will be odd and the other will be even. Hence, there is a 1-1 correspondance between the even and odd subsets.

Another property or sum that shows up a lot is the following

We also prove this using a generating function argument or a combinatorial definition argument (TODO).

Applications

Binomial coefficients show up in more places. For example, the number of ways to walk a grid from the bottom left corner to the top right corner. Another example was if we were to divide a 100 gold coins amon pirates. So we need to find integer solutions to \(a + b + c + d + e = 100\). The answer is to this is exactly \(\binom{104}{4}\). To see this, arrange all the coins in a row.

Add 4 vertical lines. So now we have 5 different sets of gold coins that will get assigned to each pirate. The question now becomes: how many different ways to put 4 vertical lines among these 100 gold coins. Observe that the number of gold coins plus the number of vertical lines is exactly 104. We want to choose exactly the 4 places where these vertical lines will go. We can do this in exactly \(\binom{104}{4}\) ways.