We’ll start by defining Quotient Rings

- \(1 \neq 0\).

- If \(a,b \in R/\{0\}\), then \(ab \in R/\{0\}\). So non-zero elements multiply to non-zero elements. In other words, \(ab = 0\) then either \(a = 0\) or \(b = 0\).

Fact: Every field is a domain. Other examples:

- \(\mathbb{Z}\) and \(K[x]\) are domains.

- The Gaussian integers are a domain \(\mathbb{Z}[i] = \{a + bi \in \mathbb{C} \ | \ a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\).

- \(\mathbb{Z}_4\) is not a domain, \([2] \neq 0\) but \([2][2] = [4] = [0]]\).

- \(\mathbb{Q}/(f_1f_2)\) where \(\deg(f_i) \geq 1\) is not a domain. (Exercise)

Fact: If \(K\) is a field and \(R \subseteq K\) is a subring such that \(1_K \in R\), then \(R\) is a domain

So basically every domain can be enlarge to be a field.

Proof

Let \(X = \{(a,b) \ | \ a, b \in R, b \neq 0\}\). Define a relation on \(X\):

We claim that this relation is an equivalence relation. (Exercise, hard to prove but use that \(R\) is a domain Side note: domains have cancellations so if \(ab = bc\) and \(a \neq 0\), then \(b = c\).)

Since we have an equivalence relation on a set \(X\), then define \(F: X/\sim\) to be the set of equivalence classes. Write \([\frac{a}{b}] \in F\) for the equivalence class of \((a,b)\). Now, define

Check that these operations are well defined and make \(F\) a field. Finally, define \(\varphi: R \rightarrow F\) by \(\varphi(a) = [\frac{a}{1}]\). Check that \(\varphi\) is an injective ring homomorphism.

Examples

- Suppose \(R = \mathbb{Z}\), then \(\text{Frac}(\mathbb{Z}) \cong \mathbb{Q}\).

- Suppose \(R = K[x]\) the ring of polynomials over a field. Then \(\text{Frac}(K[x]) = K[x]\) is the field of rational polynomials. elements in \(\text{Frac}(K[x]) = K[x]\) are of the form \(\frac{f}{g}\).

Element Types

We want to discuss factorization in a domain but before doing so, we need to see the types of elements we can find in a domain.

- Zero: the element zero is in \(R\).

- Units: These are the elements that have a multiplicative inverse.

- Reducible: If \(a \in R\), \(a \neq 0\) and \(a \not\in R^{\times}\) (not a unit), then there exists \(b,c \in R\) such that \(a = bc\). (\(b\) and \(b\) must both be non-units!)

- Irreducible: Not a zero, not a unit and not reducible. This means \(a \in R\), \(a \not\in R^{\times}\) and if \(a = bc\), then either \(b \in R^{\times}\) or \(c \in R^{\times}\).

Examples

- \(R = \mathbb{Z}\)

- Units: \(\mathbb{Z}^{\times} = \{-1, +1\}\)

- Reducible: \(\{\pm n, n \in \mathbb{N}, \text{composite}\}\)

- Irreducible: These are the elements that don't factor so \(\{\pm p, p \in \mathbb{N}, \text{prime}\}\)

- \(R = K\) where \(K\) is a field

- \(0 \in K\)

- Units: \(K^{\times} = K / \{0\}\)

- Reducible: none.

- Irreducible: none.

- \(R = K[x]\) where \(K\) is a field

- \(0 \in K[x]\)

- Units: these are polynomials of degree 0 so \(K^{\times}\)

- Reducible: polynomials that you can factor into smaller ones. \(f, \deg(f) \geq 1\) such that \(f = gh, 0 < \deg(g), \deg(h) < \deg(f)\)

- Irreducible: polynomials that you can't factor. \(f, \deg(f) \geq 1\) such that there is no \(g,h, \deg(h), \deg(g) < \deg(f)\) such that \(f = gh\)

- \(R = \mathbb{C}[x]\)

- \(0 \in C[x]\)

- Units: \(C^{\times}\)

- Reducible: \(f, \deg(f) \geq 2\)

- Irreducible: \(f, \deg(f) = 1\)

- \(R = \mathbb{C}[x]\)

- \(0 \in R[x]\)

- Units: \(R^{\times}\)

- Irreducible: One form is \(ax + b, a \neq 0\) and another form is \(ax^2 + bx + c\) where \(a \neq 0, b^2 - 4ac < 0\)

- Reducible: The rest of polynomials are reducible

Warning: If we take a look at the polynomials over the rational numbers, we will find out that there are a lot more irreducible polynomials there. Note here that the ring of polynomials with rational coefficients is contained in the ring of polynomials with the real coefficients and that’s contained in the field of rational functions over \(\mathbb{R}\). In other words, \(\mathbb{Q}[x] \subseteq \mathbb{R}[x] \subseteq \mathbb{R}(x)\). Now, take \(x^p - 2\) where \(p \geq 2\), then \(x^p - 2\) is irreducible in \(Q[x]\), reducible in \(R[x]\). (The proof is not obvious). It is a unit in \(\mathbb{R}(x)\)! so it’s important to consider the context in which we’re in.

Norm Functions

Another Example is the Gaussian Integers: \(R = \mathbb{Z}[i] = \{a + bi \ | \ a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\} \subseteq \mathbb{C}\). So \(R\) is a subring of the complex numbers and it is a domain. Since it’s a domain, we want to categorize the elements in it. But to do so, we need another tool defined as follows

So this is a function defined on the complex numbers and therefore defined on the Gaussian integers. Some properties:

- If \(z \in \mathbb{Z}[i], N(z) \in \mathbb{Z}_{\geq 0}\)

- \(N(z) = 0\) if and only if \(z = 0\)

- If \(z, w \in \mathbb{Z}[i], N(zw) = N(z)N(w)\)

- If \(z \in \mathbb{Z}[i]\), then \(z \in \mathbb{Z}[i]^{\times}\) if and only if \(N(z) = 1\)

Proof of (4):

If \(z \in \mathbb{Z}[i]^{\times}\), then \(z\) is a unit and \(zz^{-1} = 1\). We know that \(z^{-1} \in \mathbb{Z}[i]\) so \(z^{-1}\) is a Gaussian integer. So

But \(N(z)\) and \(N(z^{-1})\) are positive integers by (1). Therefore \(N(z) = N(z^{-1}) = 1\).

For the other direction when \(N(z) = 1\). Write \(z = a + bi\) where \(a, b \in \mathbb{Z}\). By definition

Therefore, \((a + bi)^{-1} = (a - bi)\).

In fact the units are just \(\mathbb{Z}^{-1}[i] = \{ \pm 1, \pm i\}\).

Example 1

Example: \(2 \in \mathbb{Z} \subseteq \mathbb{Z}[i]\). So 2 is also a Gaussian integer since \(\mathbb{Z}\) is a subring of the Gaussian integers. \(2\) is a prime number so it’s irreducible as an integer. However, is it reducible as a Gaussian integer? Observe that

So it’s definitely reducible as a Gaussian integer.

Example 2

Example: Take \(1 + i \in \mathbb{Z}[i]\). Is it reducible or irreducible in \(\mathbb{Z}[i]\)? It is in fact irreducible. We know this because \(N(1 + i) = 2\) and if there were factors \(1 + i = zw\), then

But the norm is a non-negative integer. So the only way to make this work is that either \(N(z) = 1\) or \(N(w) = 1\) so one of the factors is a unit. Thus, by definition, \(z\) is irreducible.

Associate Elements

Next, we have this definition for when two elements are associate when one element is a product of some unit times the other element.

This is in fact an equivalence relation (Exercise)

Example: In \(\mathbb{Z}\), associate classes are \(\{0\}\), \(\{\pm n\}, n > 0\). Another example is \(K[x]\), \(f \sim g\) if \(g = fc\) for some \(c \in K/\{0\}\).

Fact: If two elements are associate, then they are of the same type!

Example 3

\(3 \in \mathbb{Z} \subseteq \mathbb{Z}[i]\). Is it reducible? It is irreducible in \(\mathbb{Z}\) since it is prime. In \(\mathbb{Z}[i]\), we know that \(N(3) = N(3 + 0i) = 9\). Suppose it was reducible. This means that there exists \(z,w \in \mathbb{Z}[i]\)

To be reducible, neither \(z\) or \(w\) can be units so they can’t have a norm of 1. Therefore, we must have \(N(z) = N(w) = 3\). This a contradiction since we don’t have any Gaussian integers with norm 3 (square root of 3 from the origin).

So it’s not possible to construct an element of the form \(a + bi\) in \(\mathbb{Z}[i]\) such that \(a^2 + b^2 = 3\).

Example 4

\(4 \in \mathbb{Z} \subseteq \mathbb{Z}[i]\). Is it reducible? It is reducible in \(\mathbb{Z}\). In \(\mathbb{Z}[i]\), we know that \(4 = (2)(2)\) and \(2\) is not a unit in \(\mathbb{Z}[i]\). Not just that but we also saw that \(2\) can be factored using the previous example \(2 = (1 + i)(1 - i)\). Furthermore, we also have another way too to factor 4. Below are some of the ways

Example 5

\(5 \in \mathbb{Z} \subseteq \mathbb{Z}[i]\). Is it reducible in \(\mathbb{Z}[i]\)? It is reducible because

The factors themselves \((2+i)\) and \((2-i)\) are irreducible since the the norm \(N(2 + i) = 5\). Also note that \((2+i)\) and \((2-i)\) are not associate.

When is \(p\) reducible in \(\mathbb{Z}[i]\)?

We went through a few examples of doing this calculation but in fact we do have a proposition about this as follows

Proof

\(\Leftarrow:\) Suppose that \(p = a^2 + b^2\). Then we can write

Recall that \(N(a + bi) = a^2 + b^2\) but that means \(N(a + bi) = p\) and \(p\) is prime so it’s not 1. So neither (a + bi) or (a - bi) is a unit. Therefore, \(p\) is reducible.

\(\Rightarrow:\) Suppose that \(p\) is reducible so \(p = zw\). Therefore,

But \(p\) is prime and so we must have \(N(z)=N(w)=p\). This means that there exists some \(a, b\) such that \(z = a + bi\) where \(N(z) = p\). This means

So \(p = a^2 + b^2\) as we wanted to show. \(\ \blacksquare\)

Examples

The proof shows that for a prime to be a sum of squares is related to whether it factors as a Gaussian integer

| Reducible in \(Z[i]\) | Irreducible in \(Z[i]\) |

| \(2 = 1^2 + 1^2\) | 3 |

| \(5 = 2^2 + 1^2\) | 7 |

| \(13 = 3^2 + 2^2\) | 11 |

| \(17 = 4^2 + 2^2\) | 19 |

| \(29 = 5^2 + 2^2\) | 23 |

| \(37 = 6^2 + 1^2\) | 31 |

Notice the pattern here. The left prime numbers are congruent to 1 mod 4 while the right prime numbers are congruent to -1 mod 4.

Irreducible Elements in \(R\)

Lecture 38: To state things again, \(a \in R\) is irreducible if

- \(a \neq 0\)

- \(a \not\in R^{\times}\)

- If \(a = bc\), then one of \(b\) or \(c\) is a unit

This notion of irreducible element is kind of the replacement we have to the notion of a prime number. In fact, we can re-write this condition to make it closer.

- Given two elements in a domain \(a,b \in R\), we say that \(a\) divides \(b\) (write \(a \ | \ b\)) if there exists an element \(c \in R\) such that \(b = ac\)

- In terms of ideals. This is equivalent to saying \(b\) is in \(Ra\). It is also equivalent to saying that \(Rb \subseteq Ra\).

- \(a\) is irreducible if whenever \(b \ | \ a\), either \(b\) is a unit or \(b \sim a\). This is similar to how we defined prime numbers. if an element divides \(p\), then it's either \(p\) or \(1\)

Prime Elements in \(R\)

The reason we’re discussing this is because of another definition that might make things confusing.

This is the definition a prime element in a domain. The confusing part is that the definition of an irreducible element is the one equivalent to a prime number.

Now, this notion is actually related to irreducibility. In fact, in \(R = \mathbb{Z}\), the prime elements and the irreducible elements are exactly the same.

Proof

Suppose that \(p\) is prime. We want to show that \(p\) is irreducible so suppose that \(p = ab\) where \(a, b \in R\). We want to show that either \(a\) or \(b\) is a unit so \(a \in R^{\times}\) or \(b \in R^{\times}\). Since \(p = ab\), then \(p \ | \ ab\). But prime means that \(p \ | \ a\) or \(p \ | \ b\). So, suppose \(p \ | \ a\). This means that \(p\) is a factor of \(a\) so \(a = pc\) for some \(c \in R\). Plugging this back in the original equation to see that

But this means that \(b\) is a unit. Therefore, \(p\) is irreducible. \(\ \blacksquare\)

Irreducible but not Prime elements

The converse of the previous proposition is not true. If an element is irreducible, it won’t necessarily be prime. An example is the domain \(R = \mathbb{Z}[\sqrt{-5}] \subseteq \mathbb{C}\). It is defined as the set

It is a subring of \(\mathbb{C}\) and it has a 1 so it’s a domain. Next, we’re going to produce an element that is irreducible but not prime!

In order to show this, we need to define the norm function for \(R\) so

The norm function has the following properties

- The norm is a non-negative integer. \(N(a + b\sqrt{-5}) \in \mathbb{Z}_{\geq 0}\)

- \(N(z) = 0\) if and only if \(z = 0\)

- \(N(zw) = N(z)N(w)\), \(N(1)\)

- If \(N(z) = 1\) if and only if \(z \in R^{\times}\)

Proof (4)

\(\Rightarrow\): Suppose that \(N(a + b \sqrt{-5}) = 1\). Then

Thus, \((a + b\sqrt{-5})\) is a unit in \(R\).

\(\Leftarrow\): Suppose that \(z \in R^{\times}\) so \(z\) is a unit. Observe that

But since \(N(z)\) and \(N(\bar{z})\) are non-negative integers, then the only solution is that \(N(z) = N(\bar{z}) = 1\). \(\ \blacksquare\)

Note that we can also conclude here that the possible units in this ring are

So now back to the claim that \(2\) is irreducible but not prime. We’ll show that \(2\) is irreducible first. Computing the norm, we see that

So now suppose that \(2 = uv\) where \(u,v \in R\). Observe that

To show that \(2\) is irreducible, we need to show that \(u\) or \(v\) is a unit. So the claim is that \(u\) or \(v\) is a unit. So we need to show that either \(N(u)\) or \(N(v)\) is 1. This means that we want to show that \(N(u)=2\) is not possible. Suppose for the sake of contradiction that \(N(u)=2\). This means that

But there are no integer solutions to this. Therefore, \(2\) is irreducible in \(R = \mathbb{Z}[\sqrt{-2}]\). What about 2 being prime? Observe that

We know that \(2 \ | \ 6\). But 2 doesn’t divide either of \((1 \pm \sqrt{-5})\) in \(R\). So by defintion, \(2\) is not prime. (recall that the def was that a prime must divide either \(a\) or \(b\)). This fails in this domain because in \(\mathbb{Z}\) prime factorization is unique but in this domain we see that we have two completely different factorization.

Principle Ideal Domain (PID)

A new definition

Examples

- \(R = K\) where \(K\) is a field. Recall that fields are domains and they have two ideals.

- \(R = \mathbb{Z}\). Recall that every ideal in \(\mathbb{Z}\) is principle.

- \(R = K[x]\) where \(K\) is a field

Non-Examples

- \(R = K[x,y]\). Polynomial rings in two variables are not PIDs. One example is that $$I = (x,y)$$ is not a principle ideal. (Exercise)

- \(\mathbb{Z}[x]\). \((z,x)\) also not a principle ideal. (Exercise)

- \(R = \mathbb{Z}[\sqrt{-5}]\) is not a principle domain

This last example is a consequence of the following proposition. It contains the ideal \(I = (2, 1+\sqrt{-5})\) which is not principle. (complete proof in the lecture notes)

Proof

\(\Rightarrow\): We know that prime elements are always irreducible.

\(\Leftarrow:\): Suppose \(R\) is a PID and \(p \in R\) is irreducible. We want to show that \(p\) is prime. Since \(p\) is irreducible, then it’s non-zero. So now suppose \(p \ | \ ab\). We want to show that \(p \ | \ a\) or \(p \ | \ b\). So assume that \(p \nmid a\), we will show that \(p \ | \ b\).

Now consider the ideal generated by the two elements \(p\) and \(a\) so \(I = (p,a)\). By assumption this ideal is principle. So it is also generated by a single element \(I = (c)\). We know that \(p \in I\). So \(p\) is a multiple of \(c\) so \(p = cd\) for some \(d \in R\). Since \(p\) is irreducible, then either \(c\) is a unit \(c \in R^{\times}\) or \(d\) is a unit, \(d \in R^{\times}\).

\(d\) can’t be a unit. This is because \(p = cd\) and since \(d\) is a unit, then multiply both sides by the inverse of \(d\) to see that \(c = pd^{-1}\). But this means that \(c\) is a multiple of \(p\). So \(c \in (p)\). Thus, \((c)\) = \((p)\). (Side note: In general, \((p)=(c)\) if and only if \(p = cd\) for some unit \(d\)) Now, we know that \(p \nmid a\). But \(a \in (p,a) = (c)\). So \(a \in (p)\). This is a contradiction since \(p \nmid a\). Therefore, \(d\) can’t be a unit. Thus, \(c\) is a unit. But we know that \(I = (c)\) so \(I = R\). So \(1 \in (p,a)\). So

We know that \(p \ | \ bpx\). We also know that \(p \ | \ ab\). Therefore, \(p \ | \ b\) as we wanted to show. \(\ \blacksquare\).

The Set of Gaussian Integers is a PID

One more example of PID. We want to show that the gaussian integers are a pid but to show this, we need the following proposition

Proof

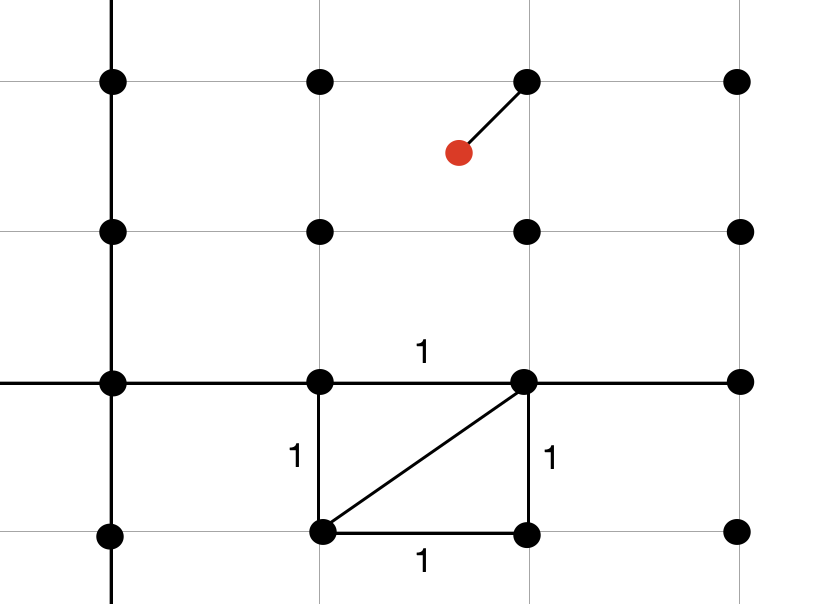

The proof for this proposition is geometric. Take the complex plane and label the gaussian integers with black dots as shown below

So suppose \(v\) is the red dot above, then distance between \(v\) and the next closest Gaussian number is always less than or equal to \(\frac{\sqrt{2}}{2}\). This is because the diagonal between any two gaussian numbers is of length \(\sqrt{2}\). So any complex number is at most a distance of 1 away from any Gaussian number.

So now take \(v\) and \(u\) and divide them \(\frac{u}{v}\). This is a complex number still. Now choose \(q \in \mathbb{Z}[i]\) that is the closest to \(\frac{u}{v}\). Observe that

So now set \(r = u - qv \in \mathbb{Z}[i]\). Thus, \(N(r) < N(v)\). \(\ \blacksquare\).

Notice here that we don’t have uniqueness statement about \(q\) and \(r\) like the division algorithm for integers. So now we can prove the following theorem about \(\mathbb{Z}[i]\)

Proof

We want to show that \(R\) is a principle ideal domain. By defintion, this means that every ideal is a principle ideal in \(R\). So let \(I \in \mathbb{Z}[i]\). We want to show that \(I\) is a principle ideal.

Use the previous proposition. If \(u, v \in \mathbb{Z}[i]\). If it’s the zero ideal, there is nothing to do. So if it’s a non-zero ideal, then it has a non-zero element. Choose an element \(d \in I/\{0\}\) in the ideal with minimal norm. We claim that \(I = (d)\).

\((d) \subseteq I\): This is easy since \(d \in I\).

\(I \subseteq (d)\): Suppose \(u \in I\), then by the previous proposition, \(u = qd + r\) where \(N(r) < N(d)\). So \(r = u - qd\). \(u \in I\) and \(qv \in I\). Thus, \(r \in I\). But \(N(r) < N(d)\) and we said that \(d\) is the element with minimum norm. So \(r = 0\). Therefore, \(u \in (d)\). So \(I = (d)\) and so \(R\) is a principle ideal domain. \(\ \blacksquare\)

References

- MATH417 by Charles Rezk

- Algebra: Abstract and Concrete by Frederick M. Goodman