Note here that for every element in the group \(G\) and every element in the set \(X\), we get a function \(\phi(g)\). This function is from \(x \rightarrow X\). Because it is a function, then we can plug in a value \(x\) such that \(\phi(g)(x) \in X\). Moreover,

Additionally, these identities force \(\varphi(g^{-1}) = \varphi(g)^{-1}\) which means that \(\varphi(g)\) is a bijection.

Alternate Notation

Given \(g \in G\) and \(x \in X\), write \(gx\) for \(\varphi(g)(x)\). So now we get a function

Re-writing the previous identities with the new notation:

Example

Tautological action by \(G = Sym(X)\) on X. What is this function?

This just gives us \(\varphi(g)=g\). This is exactly what we use when we work with permutations. A permutation is a function from \(X\) to itself. So for \(g \in G\) and \(x \in X\), we apply it like \(g(x) = gx\).

Example

Suppose \(G = SO(3)\) which acts on \(X = \mathbb{R}^3\). The action rule is given by

We’re defining a homomorphism

\(Sym(\mathbb{R}^3)\) is the group of all bijection maps from \(\mathbb{R}^3\) to itself. The map \(\varphi\) takes a matrix \(A \in SO(3)\) and produces the following function

Orbits

Next, we’ll define something called an orbit of action by \(G\) on \(X\).

Fact: orbits are equivalence classes of an equivalence relation on \(X\). So \(x \sim y\) if and only if there is some \(g \in G\) such that \(gx = y\). So, \(O(x)O(y) = \emptyset\) or \(O(x) = O(y)\). Therefore, orbits partition \(X\) into pairwise disjoint and nonempty subsets. One more fact: We action is called transitive if there is only one orbit so \(O(x) = X\).

Stabilizers

One more defintion.

Some facts:

- \(\text{Stab}(x) \leq G\)

- If \(x, y \in X\) and these elements are related such that for some \(g \in G\), we have \(y = gx\), then \(\text{Stab}(y) = g\text{Stab}(x)g^{-1}\). So if \(x\) and \(y\) are in the same orbit, then their stabilizer subgroups are conjugate.

Kernel of Action

What is the kernel of a group action? By definition, the kernel contains all the elements in \(g\) such that \(\varphi(x)\) is the identity transformation

Of course this looks exactly like the definition of a stabilizer that we just did. So,

We say that the action is faithful if \(\ker(\varphi) = \{e\}\). This is is the same as saying the homomorphism \(G \rightarrow Sym(x)\) is injective.

Example 1

Suppose \(G = D_n\) which acts on \(X = \{v_0,v_1,...,v_{n-1}\}\). The action rule is given by the homomorphism

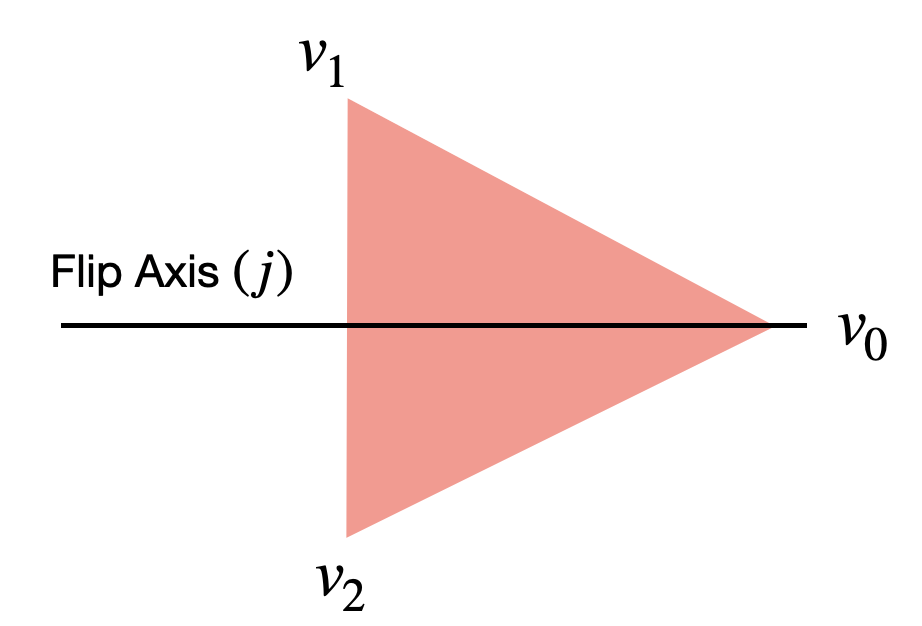

For example. Suppose \(G = D_3 = \{e, r, r^2, j, rj, r^2j\}\) with \(V = \{v_0, v_1, v_2\}\).

Given this setup. What are the orbits of the action? Pick one vertex like \(v_0\). What is the orbit of \(v_0\)? If we start with \(v_0\), then we can reach every other vertex so

So the orbit of \(v_0\) is \(O(v_0) = \{v_0, v_1, v_2\}\). So there is only one orbit and in this case the action is transitive. What about the stabilizers? these are the set of elements of \(G\) that fix \(x\). For example, if we take \(v_0\), then we know that \(e\) fixes \(x\) so it’s in the set. Is there any other element such that if we hit \(x\) with it, we get \(x\) back? Notice that \(j\) does that since \(v_0\) is on the flip axis. We can do the same calculation for \(v_1\) and \(v_2\) to see that

Example 2

Let’s take another example. Suppose that \(G = SO(3)\) and \(X = \mathbb{R}^3\). Take the action given by the homomorphism

What is the orbit of \(v\)? Take a unit vector and compute its orbit under the action of \(SO(3)\). We elements do we get when we rotate this vector by any rotation in \(SO(3)\)? What vector do we get? We get another unit vector. In fact, given a vector with norm \(\lVert R \rVert = R\), we will get

We get the set of vectors in \(\mathbb{R}^3\) with length \(R\). So a sphere of radius \(R\) centered at the origin. (Except for the zero vector where its orbit is 0 so \(O(0) = \{0\}\)).

What about the stabilizers? If \(v\) is the zero vector, that’s easy because it’s all of \(SO(3)\). Any matrix \(A\) satisfies \(A0 = 0\). But for non-zero vectors, its the rotations of any angle around an axis through \(v\).

Is this a faithful? Is there any matrix \(A\) that fixes every vector \(v\) besides \(I\)? No, in fact, the kernel has only the identity matrix.

Orbit Stabilizer Theorem

A consequence of this theorem is a formula for the size of the orbit

This is useful when the group is finite. So when it’s finite, then \(|O(x)| = \frac{|G|}{\text{Stab}(x)}|\). So the size of any orbit has to divide the order of the group.

Proof

We need to give a bijection. Consider the formula that takes a left coset \(gH\) to what you get when you apply the action on \(x\).

Step 1 involves showing that this is well defined. So given that \(gH = g'H\), then \(gx = g'x\). The reason why they would be equal is that \(H\) is simply the stabilizer \(\text{Stab}(x)\). Step 2 is showing that this is indeed a bijection.

Actions by \(G\) on \(X = G\)

Suppose you have a group \(G\). What will happen if it acts on its own set. So

There several of these. For example, we have the Left Regular Action. This is given by the homomorphism

What are the orbits of this action? For example, the orbit of \(e\) is everything

What about the stabilizers?

A consequence of this is that the kernel of the action is, \(\ker(\lambda) = \{e\}\). Therefore, we have a faithful action. This actually led to the next big theorem which is Cayley’s Theorem

Proof

Use the left regular action \(\lambda: G \rightarrow Sym(G) \cong S_n\). This is a faithful action which means that this action is injective. Therefore, \(G\) is isomorphic to the image subgroup which is \(Sym_n\)

Right Regular and Conjugate Actions

We also have a Right Regular Action (though we won’t use it)

And the Conjugate Action

This is an action \(c(g_1) \circ c(g_2) = c(g_1g_2)\). The orbits of the conjugation action are called conjugacy classes. For example, if we have \(x \in X \in G\), then the conjugacy class of \(x\) is. It is a subset of the group \(G\)

For the stabilizers, if we have \(x \in X = G\), then

The kernel

We actually do a relavent Theorem here

Example

Suppose \(G = D_3 = \{e, r, r^2, j, rj, r^2j\}\). We want to compute the orbits which are now the conjugacy classes for each element. For example, the orbit/conjugacy class of the identity is just the identity, since conjugating the identity by any element in \(g\) gives us the identity back.

For \(r\) we we can try conjugating by every element of \(g\) but we will see that we will always get \(r\) and \(r^2\) back.

Therefore, \(Cl(r) = \{r, r^2\}\). Finally, let’s find the conjugacy class of \(j\)

We’ll get \(Cl(j) = \{j, rj, r^2j\}\). Now, we can do the stabilizers. The stabilizer of \(e\) is any element that \(e\) fixes so it’s all of \(G\). What about \(r\)?

- By the previous theorem, \(|Cl(x)| = \frac{|G|}{|\text{Cent}(x)|}\). Since \(|Cl(r)|=2\), then we must have three elements in the centralizer.

- We also know that the centralizer is a subgroup. So we must have the identity and not just that but we must have the element itself since it commutes with itself. But the subgroup is closed so it must have any product

Therefore, \(\text{Cent}(r) = \{e,r,r^2\}\). Similarly, \(\text{Cent}(j) = \{e,j\}\). What if we take another element that’s in the same orbit like \(rj\). We will see that \(\text{Cent}(rj) = \{e, rj\}\).

In fact, all the dihedral odd groups will look similar to what we found above for \(D_3\). The even groups however are slightly different. \(D_4\) for example has an interesting element which is \(r^2\). It is interesting because it commutes with every other element in \(G\). Therefore, in \(D_4\), the center of the group is \(Z(D_4) = \{e, r^2\}\). When \(n\) is odd, \(Z(D)\) contains the identity only.

References

- MATH417 by Charles Rezk

- Algebra: Abstract and Concrete by Frederick M. Goodman