Last time we developed Quotient Groups. The next theorem provides a recipe for constructing homomorphisms for Quotient Groups.

Let \(K = ker(\phi)\) be a normal subgroup such that \(N \subseteq K\). Then

There exists a homomorphism \(\varphi': G/N \rightarrow H\) with formula $$ \begin{align*} \varphi'(aN) = \varphi(a) \end{align*} $$ and $$ \begin{align*} ker(\varphi') &= K/N = \{aN \ | aN \subseteq K\} \unlhd G/N \\ \phi'(G/N) &= \phi(G) \leq H \end{align*} $$

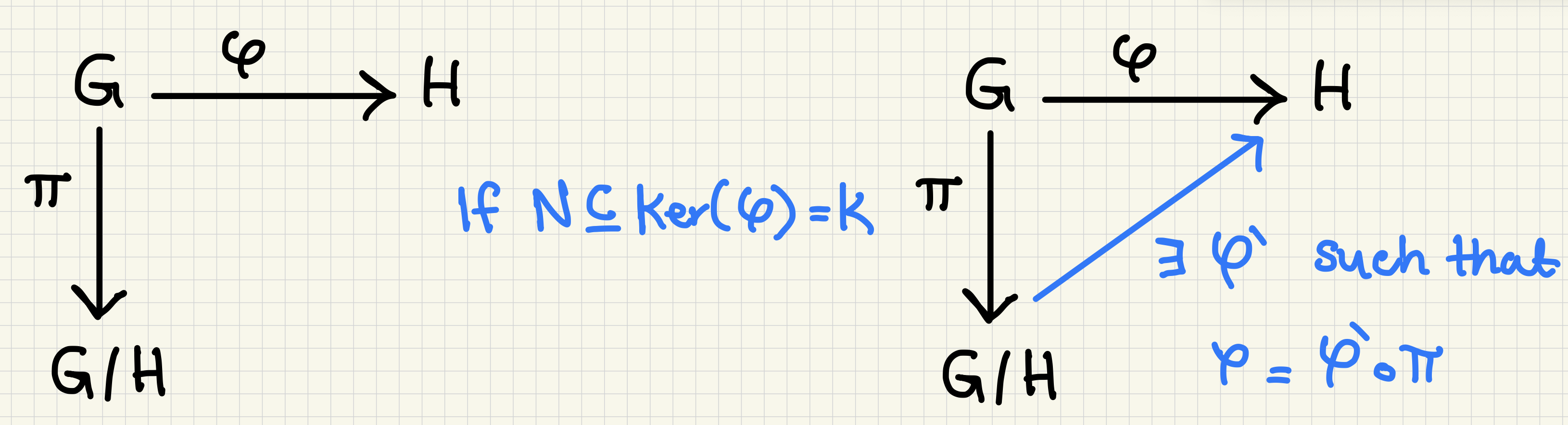

In a picture, once we have the requirement \(N \subseteq K\) where \(K = ker(\phi)\), then we get this homomorphism \(\varphi'\) between \(H\) and \(G/N\). This new homomorphism \(\phi'\) is unique.

In short, we’re following a recipe to construct a homomorphism. Given a homomorphism \(\varphi \ : \ G \rightarrow H\) and a normal subgroup \(N\) that is a subset of \(ker(\varphi) = K\) (which means that \(\varphi(N) = \{e\}\) since every element in the kernel is sent to the identity). THEN, we get another homomorphism \(\varphi\) from \(G/N\) to \(H\). The homomorphism is given by \(\varphi'(aN) = \varphi(a)\).

Proof

(1) First we need to check that \(\varphi'\) is well defined. This means that want to show that if \(aN = bN\) (in \(G/N\)), then \(\varphi'(a) = \varphi'(b)\) which is \(\varphi(a) = \varphi(b)\) in \(H\) by how we defined \(\varphi'\) above. Re-write \(aN = bN\) as

So \(b^{-1}a \in N\). Now we can apply \(\varphi\) on it to get

So it’s well defined as we wanted to show. \(\blacksquare\)

(2) Next, we want to show that it is a homomorphism. To see that observe that

On the other hand

And so we’re done. \(\blacksquare\)

(3) Finally, we need to prove the conclusions of the theorem. The second statements claims that \(\phi'(G/N) = \phi(G)\). But this is true by how we defined \(\varphi'\). For the first statement which claims that \(ker(\varphi') = K/N = \{aN \ | \ aN \subseteq K\}\). First, we know that by the definition of the kernel that

Notice now that \(N\) is a subgroup of \(K\). This means that any coset of \(N\) will be contained in the corresponding coset of \(K\) so \(aN \subseteq aK\). But here it is the trivial coset so \(aK = eK = K\).

Isomorphism Theorem

Let \(K = ker(\phi)\) be a normal subgroup such that \(N = K\) (unlike before where \(N \subseteq K\)). Then

There there is a isomorphism \(\varphi': G/N \rightarrow H\) with formula (same as before) $$ \begin{align*} \varphi'(aN) = \varphi(a) \end{align*} $$ Unlike before, now \(\phi'(G/N) = H\) and the kernel \(ker(\varphi') = \{eN\}\) (the trivial coset of \(N\)).

So we have the same conditions as before except that \(N = K\) and the \(\phi\) is surjective. So we can apply the homomorphism theorem from before and we’ll get the same results as before. That is, a homomorphism \(\phi'\). But now since \(\phi\) is surjective and its image is the same as the image of \(\phi'\), then \(\phi'\) is also surjective.

Moreover, its kernel per the homomorphism theorem is \(\{aN \ | \ aN \subseteq K\}\) (collection of all cosets of \(N\) that are contained in \(K\)). But now \(N = K\). There is only one coset of \(N\) contained in \(N\) which is the trivial coset \(eN\). so \(ker(\phi') = \{eN\}\). This implies that \(\phi'\) is injective. So \(\phi'\) is now a bijection which means that it’s an isomorphism.

Example 1

- Let \(H = \langle a \rangle\) be a finite cyclic group of order \(n\).

- Let \(G = (\mathbb{Z}, +)\).

- Let \(N = \mathbb{Z}n \unlhd \mathbb{Z}\) the group of multiples of \(n\) which is a subgroup of \(G = \mathbb{Z}\).

- Let \(\phi: \mathbb{Z} \rightarrow H \) be a surjective homomorphism by the formula \(\phi(m) = a^m\)

- The kernel of \(\phi\) is \(ker(\phi) = \{m \in \mathbb{Z} \ | \ a^m = e\}\). The kernel is the set of all the multiples of the order of \(\langle a \rangle\) so it's \(\mathbb{Z}n\) where \(n\) is the order.

Applying the Isomorphism Theorem, we get a new isomorphism

Reminder: \(\mathbb{Z}/\mathbb{Z}n = \mathbb{Z}_n\)

Example 2

- Let \(\mathbf{F}^{x} = \mathbf{F} \ \{0\}\).

- Let \(GL_n(\mathbf{F}) = \{ A \in Mat_{n \times n}(\mathbf{F})\) such that \(A\) is invertible\(\}\) with matrix multiplication.

- Let \(\phi: GL_n(\mathbf{F}) \rightarrow \mathbf{F}^{x} \) be a homomorphism by the formula \(\det(AB) = \det(A)\det(B)\). Is the determinant surjective? for any number \(a \in \mathbf{F}\), can we find a matrix satisfying such that its determinant is \(a\)? Yes! consider $$ \begin{align*} \begin{pmatrix} a & 0 & ... & 0 \\ 0 & 1 & ... & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & \dots & 1 \\ \end{pmatrix}. \end{align*} $$ The determinant of this matrix is \(a\). So this homomorphism is surjective.

- The kernel of \(\phi\) is the set of invertible matrices such that their determinant is the identity matrix. \(ker(\phi) = \{A \in GL_n(F) \ | \ \det(a) = 1\}\). This set is called the special linear group or \(SL_n(\mathbf{F})\) In fact it is a normal subgroup of \(GL_n(F)\).

The Isomorphism Theorem tells us that \(GL_n(\mathbf{F})/SL_n(\mathbf{F})\) is isomorphic to \(\mathbf{F}^{x}\)

Example 3

We’re going to show that \(S_4 / N \approx S_3\).

To do this, we’re going to produce a homomorphism from \(S_4\) to \(S_3\). But \(S_3\) is isomorphic to \(Sym(X)\) where \(X\) has 3 elements.

\(S_4\) is the set of permutations of a 4 element set. There is a trick that we can use to construct interesting homomorphisms out of a permutation group which is to find structures on the set that we’re permuting. For example define \(X\) to be the set of partitions of \(\{1, 2, 3, 4\}\) into two disjoint subsets of 2 each. So

So we have 3 different ways of grouping these 4 elements. Suppose now we have a permutation in \(S_4\) as follows

So now let’s apply \(g\) on the three elements in \(X\)

So for the first example, we’re given \(12|34\). We’ll look up where each element goes in \(g\). For example 1 goes to 2, 2 goes to 3, 3 goes 1 and 4 stays fixed. So that’s exactly what we get which is \(S_3\).

So the permutation \(g\) sends \(S_1\) to \(S_3\), \(S_2\) to \(S_1\) and \(S_3\) to \(S_2\).

Let’s now take another permutation \(g'\) in \(S_4\)

So now let’s apply \(g'\) on the three elements in \(X\)

So \(g'\) just takes \(X\) to itself

So here are some claims about \(\varphi\)

- \(\varphi\) is a homomorphism from \(S_4\) to \(S_3\).

- \(\varphi\) is surjective. Recall that \(|S_4| = 24\) while \(|S_3| = 6\). (We still need to check (homework))

- \(K = ker(\phi)\) is a normal subgroup of \(S_4\). We can further deduce the order of \(K\). How? We know by the Isomorphism Theorem that the quotient group \(S_4/K\) is isomorphic \(S_3\) because \(\varphi\) is a surjective homomorphism and \(K\) is a normal subgroup. This tells us that these two groups have the same size. Since \(K\) is normal, we also know that the quotient group is the number of cosets. But by Lagrange's Theorem we know that \(\frac{|S_4|}{|K|}\) is equal to the number of cosets. So \(\frac{|S_4|}{|K|} = |S_4/K| = |S_3|\). Therefore, we see that \(|K| = 4\).

- In fact \(K = \{e, (1 \ 2)(3 \ 4), (1 \ 4)(2 \ 3), (1 \ 3)(2 \ 4)\} \)

Notice here that we first proved that \(|K| = 4\) before finding the elements in \(K\). It’s just easier to verify that some element is in the kernel rather than finding the elements first.

Example 4

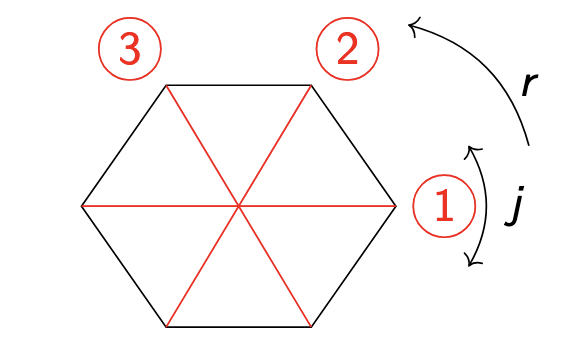

Suppose that \(n \geq 3\). Let \(D_{2n}\) be the symmetries of regular \(2n\)-gon (even number of vertices.)

We already know that if we have a symmetry of an \(n-\)gon, we get a permutation of its vertices. But there are other ways to construct a homomorphism. Consider the following homomorphism

where \(X\) be the set of diagonals of the polygon. For example, for \(n = 3\), we have 6 vertices. But we let’s think of the diagonals. We have 3 diagonals. Notice here that any symmetry will take a diagonal to another diagonal. If we label the diagonals, then a rotation will take diagonal 1 to diagonal 2 for example and diagonal 2 to diagonal 3 as shown below.

In fact, this homomorphism is surjective.

The kernel of this homomorphism is a normal subgroup of \(D_6\) and by the Isomorphism Theorem, the quotient group \(D_6/K\) is isomorphic to \(S_3\). How big is \(K\)? \(D_6\) has 12 elements and \(S_3\) has 6 elements. So \(K\) must have \(2\) elements. The kernel is \(\{e, r^3\}\).

References

- MATH417 by Charles Rezk

- Algebra: Abstract and Concrete by Frederick M. Goodman