\(gH = \{gh \ | \ h \in H\}\) is called a left coset of \(H\) in \(G\).

\(Hg = \{hg \ | \ h \in H\}\) is called a right coset of \(H\) in \(G\).

Examples

Example 1: Let \(D_4 = \{e, r, r^2, r^3, j, rj, r^2j, r^3j\}\). where \(r^4 = e = j^2\) and \(jr = r^{-1}j\).

Define the subgroup \(H = \langle j \rangle = \{e, j\}\). The left cosets are:

Notice here that none of the elements overlap between the sets so this gives us a way to partition the set \(G\) into four pairwise disjoint subsets (We’ll prove this next). The right cosets are

Example 2: Let \(G = \mathbb{Z}\) (with addition) and take \(H = \mathbb{Z}n \leq G\) where \(n \geq 1\).

The left coset is \(a + H = a + \mathbb{Z}n = \{a + kn \ | \ k \in \mathbb{Z}\}\)

The left coset is \(H + a = \mathbb{Z}n + a\) which is the same as the right coset. This happens because the group is abelian!

Another name for these cosets are the congruence class \([a]_n\).

Cosets are Pairwise Disjoint

Next we show why these subets must be pairwise disjoint.

- \(X \cap Y = \emptyset\).

- \(X = Y\).

Proof

We’ll prove that not (1) implies (2) (to prove an or statement).

Suppose that \(g \in X \cap Y\). We want to show that \(X = Y\). Since \(X\) and \(Y\) are left cosets, then we can write \(X = xH\) and \(Y = yH\) for some \(x, y \in G\). Since \(g \in X \cap Y\), then we can write \(g = xh_1 = yh_2\) for some \(h_1, h_2 \in H\). Observe now that

Likewise

Now, let \(xh \in xH\), then

But this implies that \(xh \in yH\). So \(xH \subseteq yH\). Likewise, let \(yh \in yH\), then

so \(yh \in xH\) and \(yH \subseteq xH\). Therefore \(xH = yH\). \(\blacksquare\)

Based on this, we have the following proposition

- \(a \in bH\).

- \(b \in aH\).

- \(aH = bH\).

- \(b^{-1}a \in H\).

- \(a^{-1}b \in H\).

Proof (book)

Suppose \((a)\) holds. Let \(a \in bH\). Then we can write \(a = bh\). Since \(H\) is a subgroup, then we know \(h^{-1} \in H\). So we can write \(b = ah^{-1}\). But \(ah^{-1}\) is in \(aH\) by the definition of a left coset which is what we wanted to show. With similar reason \((b)\) also implies \((a)\).

For \((c)\), we want to show that \(aH \subseteq bH\) and \(bH \subseteq aH\). To show that \(bH \subseteq aH\), we want to show that for any arbitrary element \(x\) in \(bH\), that \(x\) is also in \(aH\). So consider any \(x \in bH\). By the definition of a coset, we can write \(x = bh\) for some \(h \in H\). Now suppose that \((b)\) holds and so we have \(b \in aH\). This means that we can write \(b = ah_1\) for some \(h_1 \in H\). But this means that we can write \(x = bh = ah_1h\). The product \(h_1h\) is in \(H\) because \(H\) is a subgroup. Furthermore, \(ah_1h\) must be in \(aH\) by the definition of a coset. Therefore, \(x = bh \in aH\) and so \(bH \subseteq aH\) as we wanted to show. Since \((b)\) also implies \((a)\) we can use a similar reasoning to show that \(aH \subseteq bH\).

For \((d)\) ….

Lagrange Theorem

Based on what we learned so far, we can now present the following important results

This works well for infinite groups as well because all we need is a bijection to show they have the same cardinality.

Proof

We know the coset \(aH\) is constructed such that each element is appended on the left by \(a\). So naturally construct the following bijection

This works. For any element in \(x \in aH\), the inverse is just \(a^{-1}x\). Likewise we can construct a bijection for the right coset as follows

This leads to Lagrange Theorem.

Proof

We know by the previous proposition that all cosets have the same cardinality as \(H\) itself. Moreover, we know that the collection of left cosets \(\{aH, a \in G\}\) partitions \(G\) into pairwise disjoint subsets. Therefore

From this we see that \(|G| = m|H|\) as we wanted to show. \(\ \blacksquare\)

This in turn leads to the following theorem:

Proof

[TODO]

More Definitions in Cosets

The index could be infinite but we only care when the index is finite.

Using Lagrange’s Theorem also note that if \(G\) is finite, then \([G : H] = \frac{|G|}{|H|}\).

Also note that \([G:H]\) can be finite even if \(G\) and \(H\) are infinte.

Example: Let \(G = \mathbb{Z}, H = \mathbf{Z_n}\) where \(n > 0\). Then the index of \(\mathbb{Z}_n\) inside \(\mathbb{Z}\) is the number of left cosets which is the number of congruent classes, \([\mathbb{Z}:\mathbb{Z}_n] = n\)

We might ask why is the definition is in terms of the number of left cosets and not the right cosets. The answer is in the next proposition

The actual bijection is to take all the elements in the left cosets, take their inverses. The collection of inverses will be the elements in the right cosets. Why is this true?

If \(X = aH = \{aH \ | \ h \in H\}\), then \(X^{-1} = \{ (ah)^{-1} \ | \ h \in H \} = Ha^{-1}\).

So why not use \(aH \rightarrow Ha\)? This might not be defined.

- \(H\) is a normal subgroup.

- Left \(H\)-cosets are the same as right \(H\)-cosets.

- Every left \(H\)-coset is contained in a right \(H\)-coset.

Proof

\((3) \rightarrow (1)\):

Suppose every left \(H\)-coset is a subset of some right \(H\)-coset. Let \(a \in G\). We want to show that \(H\) is a normal subgroup. So we want to show that \(aHa^{-1} \subseteq H\). Given that every left coset in contained in a right coset, consider the left coset \(aH\). This coset is contained in some right coset. Since \(a \in aH\), then \(a\) must be in the right coset as well. We can claim that \(aH \subseteq Ha\). So for any \(h \in H\), \(ah = h'a\) for some \(h' \in H\). Observe that \(aha^{-1} = h'\) for some \(h' \in H\). In other words, \(aHa^{-1} \in H\) and \(H\) is normal. \(\ \blacksquare\)

Applications

Let’s look at some applications of the order theorem.

Proof

Let \(g \in G\). By the order theorem, the order of \(g\) must divide \(|G|\) which is a prime number. So \(o(g) \in \{1, p\}\). \(\{e\}\) is the only group with order 1 and \(|G| = p > 1\) so we must have an element \(g \in G\) such that \(g \neq e\). So \(o(g) = p\). But we also said that the order of an element is also the size of the cyclic group generated by \(g\) so \(|\langle g \rangle| = p\). Therefore, we must have \(G = \langle g \rangle\). \(\ \blacksquare\)

Proof

Let \(g \in G\). The order of \(g\) has to divide 4 by the order theorem so \(o(g) \in \{1,2,4\}\). If \(o(g) = 4\), then \(o(g) = 4\) and \(\langle g \rangle = G\) so \(G\) is cyclic and so it is isomorphic to \(\mathbb{Z}_4\). If \(o(g) \neq 4\). Then \(G\) must have 4 distinct elements so \(G = \{a, b, c, d\}\) none of the elements can have order 4. \(a, b, c\) can’t have order 1. So they must be of order 2 and their squares must be the identity. This gives us enough information fill out the multiplication table of this group as follows:

| \(e\) | \(a\) | \(b\) | \(c\) | |

| \(e\) | \(e\) | \(a\) | \(b\) | \(c\) |

| \(a\) | \(a\) | \(e\) | \(c\) | \(b\) |

| \(b\) | \(b\) | \(c\) | \(e\) | \(a\) |

| \(c\) | \(c\) | \(b\) | \(a\) | \(e\) |

Subgroups of \(D_5\)

Let’s use Lagrange’s Theorem next. Specifically, let’s analyze the subgroups of the dihedral group \(D_5\). First,

The first we want to do when finding its subgroups is find the order of each element in \(D_5\). We know \(|D_5| = 10\) so the orders of the elements must divide 10. We also know that each flip’s order is 2 (because we established previously that \(j^2 = e\)). We also established previously that \(r^5 = e\). The rest of the elements must have their order \(\in \{1,2,5,10\}\) by the Order Theorem. In fact

Now, any subgroup of \(G\) must have order dividing the order of \(G\) so they must divide 10 by Lagrange’s Theorem. So \(|H| \in \{1,2,5,10\}\). Note here that 2 and 5 are prime! so by the previous proposition, they must be cyclic. We list the subgroups as follows by their orders:

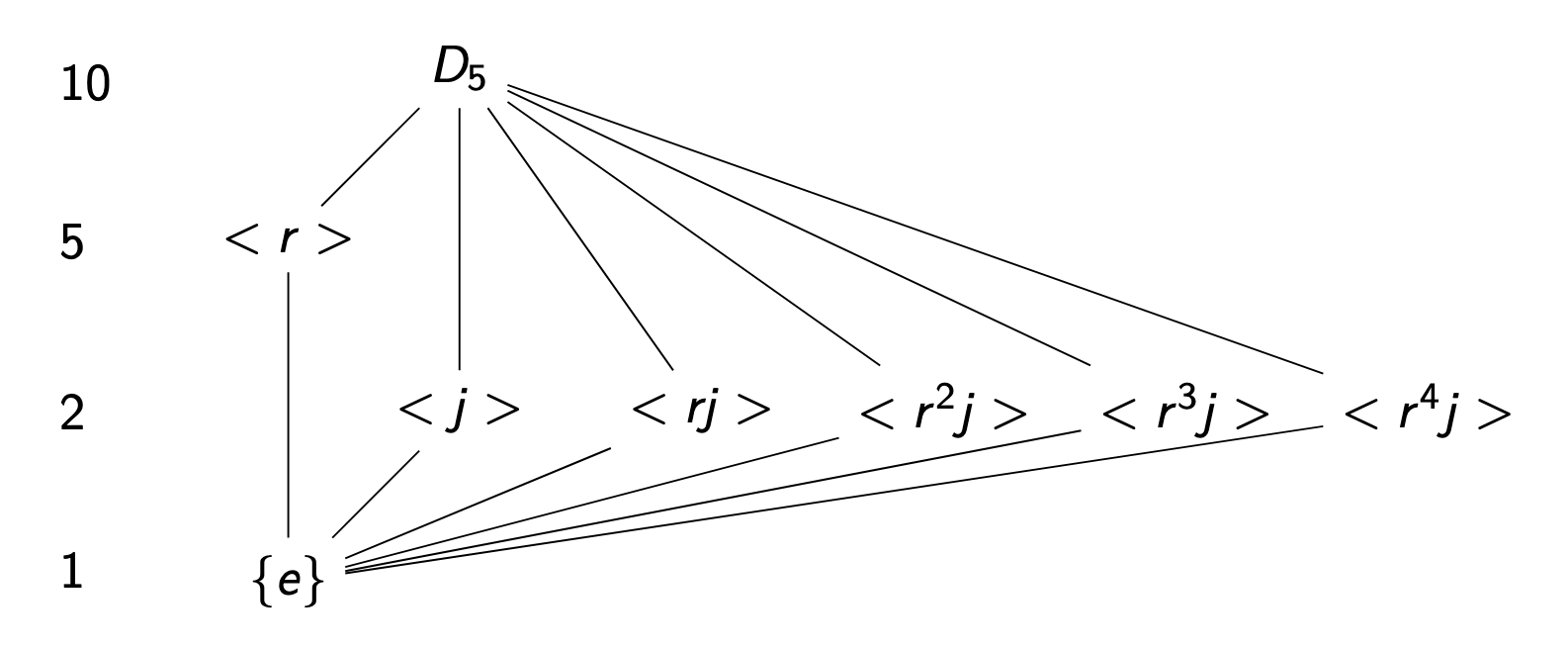

We can draw the subgroups as follows

Notice that there is 1 group of order 5 while there are 5 groups of order 2.

Subgroups of \(D_9\)

We list the elements of \(D_9\) as follows

First, let’s find the order of each element knowing that the order of each flip is 2 and know that element must have an order that divides 18. [Side note from studying. Note that \(\langle r \rangle\) is a cyclic subgroup of order 9 and it has the elements \(r, r^2, r^3, ..., r^8\). Each element inside the subgroup must have order \(n / gcd(n,power)\) where n is the order of \(r\). So the order of \(r^3\) is \(9/gcd(9,3) = 3\). Remember that the order of an element depends on the operation of the group and it is the least power \(k\) such that \(g^k = e\).]

For the subgroups, if the order was 2 or 3, then we know they must be cyclic. In this case, we know all the subgroups of order 2 (all the flips) are cyclic unique subgroups. For orders 3 and 6, they could be cyclic but they could also fail to be cyclic. Take order 3, first we check if there are elements of order 3 in the group. Yes, we have \(r^3\) and \(r^6\). Why we look for those? Because by definition of the order of an element, they will each generate a subgroup of order 3 (Recall from the subgroups lecture \(|\langle g \rangle| = o(g)\)). In fact, here \(r^3\) and \(r^6\) both generate the same subgroup.

What about order 6? Are there any elements of order 6? No, therefore, there aren’t cyclic groups of order 6. One thing we do know is that any element in that subgroup must have order dividing the order of the subgroup. So any element in it must divide 6 so the choices are \(\{1,2,3,6\}\). Here it’s trial and error. For example guessing \(\langle r^3, j \rangle\), we see that it consists of

Notice here that \(jr^3 = r^6j\) by the identity \(jr^k = r^{-k}j\). Is there another group of order 6? Instead of \(j\), we can try another element of order 3:

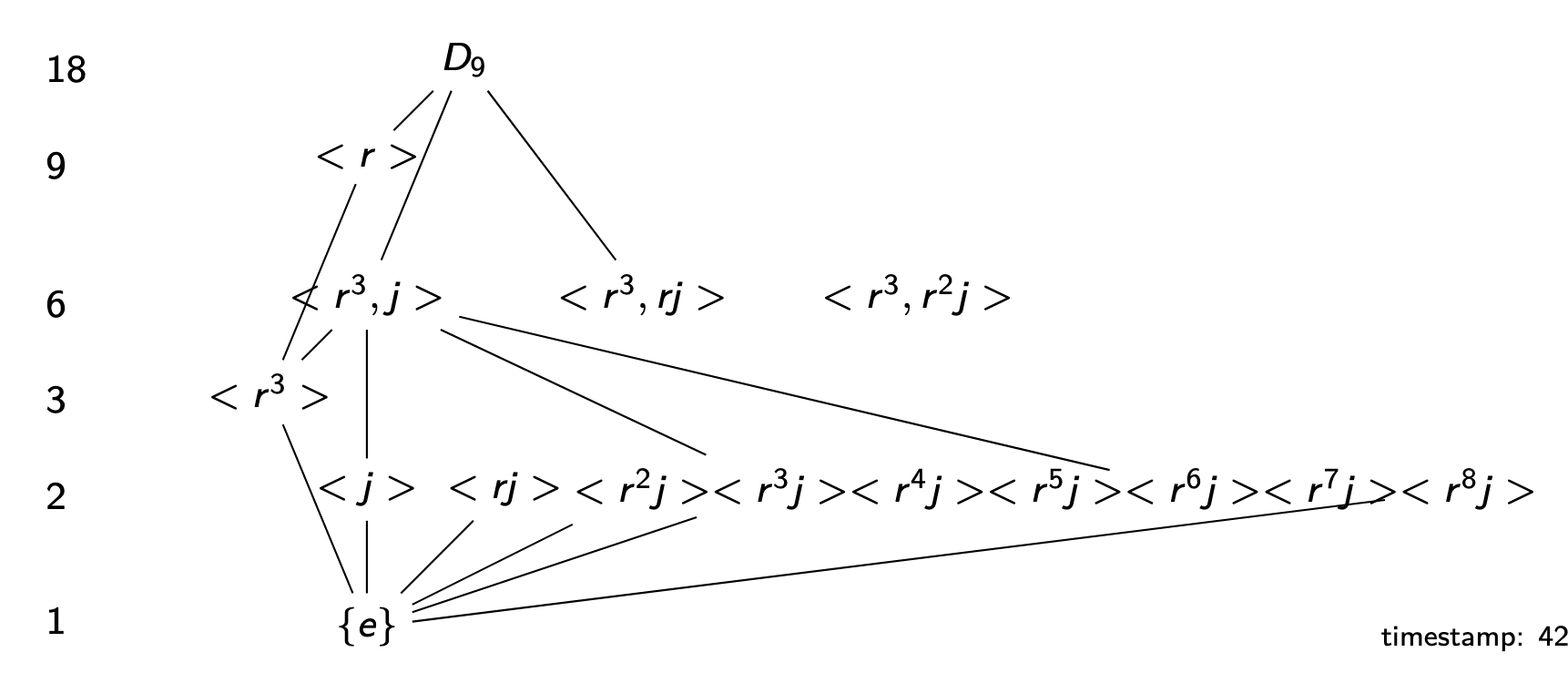

Overall, we’ll have the following subgroups. These lines indicate whether the subgroup is contained in another subgroup so \(\{e\}\) is contained in all of them. \(\langle r^3 \rangle\) is contained in \(\langle r^3, j \rangle\).

References

- MATH417 by Charles Rezk

- Algebra: Abstract and Concrete by Frederick M. Goodman