Before discussing the Dihedral group, we will discuss the symmetries of the disk. Why? if you inscribe a regular polygon inside a circle, observe that the symmetries of the polygon are a subset of the symmetries of the circle/disk. So it’s helpful to start there.

Symmetries of the Disk

Let \(D \leq SO(3)\) be the rotational symmetries of the unit disk: \(\{(x,y,0) \ | \ x^2 + y^2 = 1 \}\). There are two types of rotations in \(D\). A rotation \(g\) around the \(z-\)axis so the \(z-\)axis remains fixed and we’re spinning the disk around it. Here \(g(e_3) = e_3\). The other type is when we flip the disk so the \(z-\)axis is now reversed. Here \(g(e_3) = -e_3\).

Rotations Around the \(z-\)axis

A rotation around an arbitrary angle which is \(r_{\theta} = Rot_{e_3}(\theta)\). It is always a symmetry around the unit disk. Note here that \(r_0=e\) and if we rotate by more than \(2\pi\), then it’s a rotation we’ve seen before. So \(r_{\theta + 2\pi n} = r_{\theta}\) so we need to specify \(r_{\theta}\) where \(\theta \in [0, 2\pi)]\). Note also that \(r_{\theta}^{-1} = r_{-\theta}\).

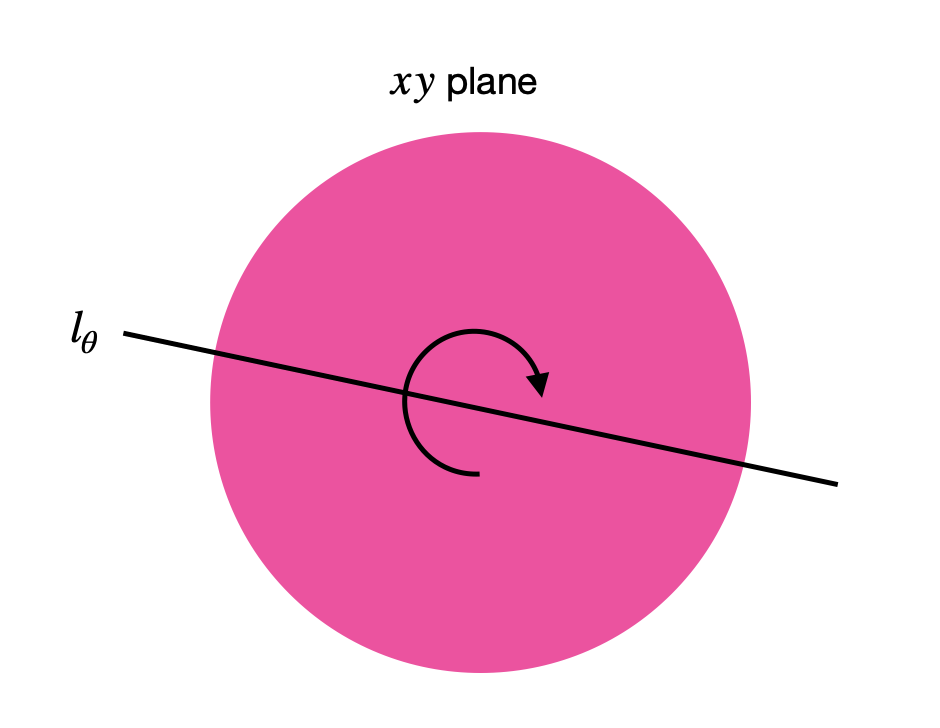

Rotations Around the a Line in the \(xy-\)axis (Flips)

Here the \(z-\)axis will get reversed since we’re flipping the disk by \(180^{\circ}\) (so \(e_3\) will now be \(-e_3\) facing the opposite the direction). The rotation axis itself is parallel to the \(xy\) plane. And we write \(j_{\theta} = Rot_{u_{\theta}}(\pi)\). Just draw a disk and draw any line that goes through the center. This line will be the rotation axis that is fixed and we’re flipping over it.

The rotation vector can written as

This vector spans a line \(l_{\theta} = \mathbb{R}u_{\theta}\). This line is in the \(xy\) plane that goes through the vector \(u\). Note here that adding another rotation of \(\pi\) will not change the line so \(j_{\theta + \pi n} = j_{\theta}\). However, the vector \(u_{\theta}\) though will face the other direction after adding \(\pi\) and so \(u_{\theta+\pi} = -u_{\theta}\). Moreover, \(j^2_{\theta} = e\).

Multiplication of Rotations and Flips

To describe the group structure, we want to see what happens if we perform two rotations, two flips, a rotation followed by a flip and a flip followed by a rotation.

- Two Rotations: This case is easy, since two rotations around the \(z-\)axis (spinning around) is just another rotation so

$$ \begin{align*} r_{\alpha}r_{\beta} = r_{\alpha+\beta} \end{align*} $$

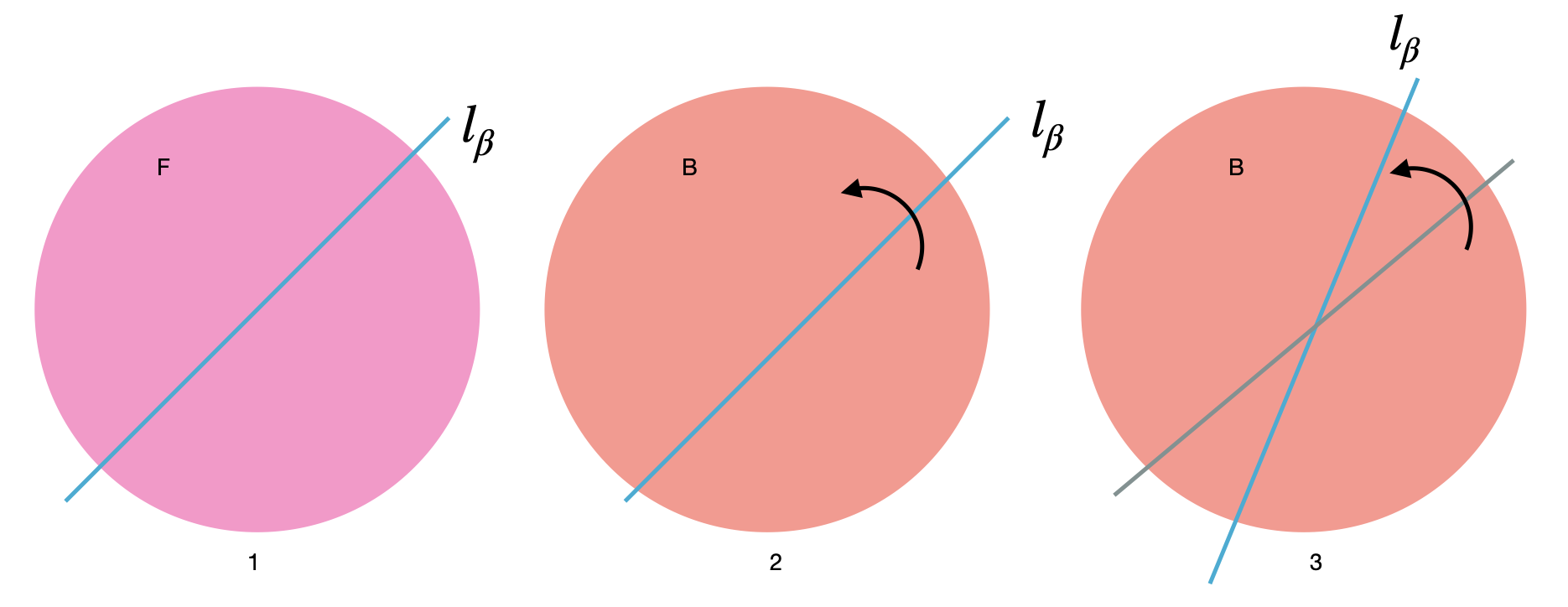

- A Flip by \(\beta\) followed by a Rotation of \(\alpha\) \(r_{\alpha}j_{\beta}\):

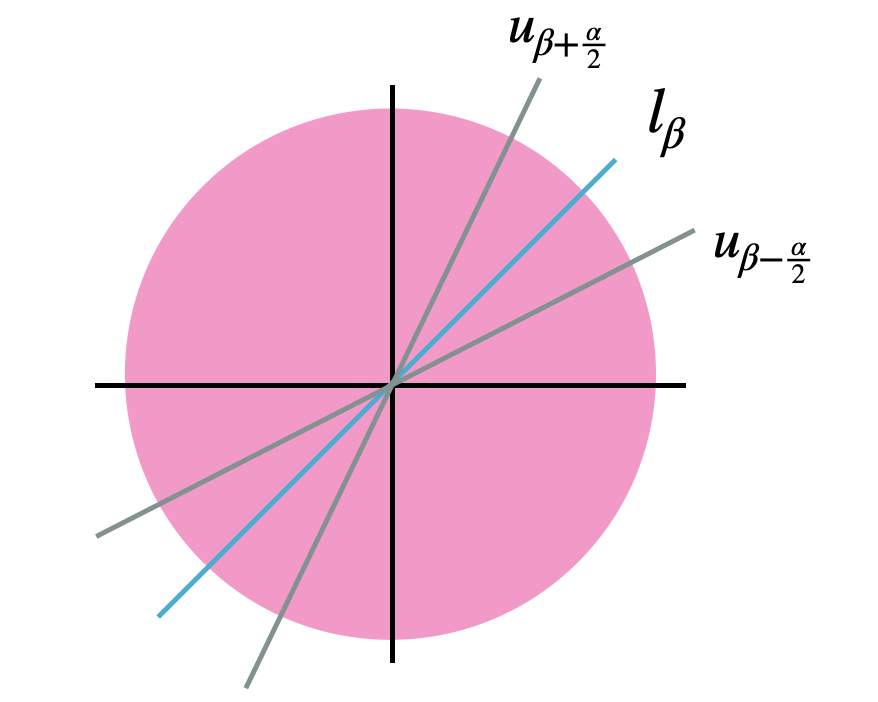

$$ \begin{align*} r_{\alpha}j_{\beta} = j_{\beta+\frac{\alpha}{2}} \end{align*} $$But why? We first flip the disk where \(l_{\beta}\) is fixed like before. After the flip, we rotate the disk around the \(z-\)axis by \(\alpha\) as illustrated below

So what we want is to compose these two operations into one and find where the fixed rotation axis will be. If you turn the third figure back to the front and now you want to use one flip to get to the same exact positions of the lines in the third figure, you'll see that the new axis will be \(u_{\beta+\frac{\alpha}{2}}\).

- A Rotation followed by a Flip \(j_{\alpha}r_{\beta}\):

$$ \begin{align*} j_{\alpha}r_{\beta} = j_{\alpha-\frac{\beta}{2}} \end{align*} $$

- Two Flips \(j_{\alpha}j_{\beta}\). Now this is clearly a rotation since we're back to the same face. but we're flipping by a different axis each time. The final rotation is the difference of the two times two. (TODO: why times 2?)

$$ \begin{align*} j_{\alpha}j_{\beta} = r_{2(\alpha-\beta)} \end{align*} $$

Elements of \(D\)

Based on the previous list, we can now list precisely the elements of (D). We have

- \(r_{\theta}\) for unique \(\theta \in [0, 2\pi)\). Noting that \(r_{\theta + 2\pi n} = r_{\theta}\)

- \(j_{\theta}\) for unique \(\theta \in [0, \pi)\). Noting that \(j_{\theta + \pi n} = j_{\theta}\)

In addition to the multiplication table based on the previous discussion.

- \(r_{\alpha}r_{\beta} = r_{\alpha+\beta}\)

- \(r_{\alpha}j_{\beta} = j_{\beta+\frac{\alpha}{2}}\)

- \(j_{\alpha}r_{\beta} = j_{\alpha-\frac{\beta}{2}}\)

- \(j_{\alpha}j_{\beta} = r_{2(\alpha-\beta)}\)

Alternative Description of \(D\)

Another description is that let \(j = j_{0}\). Then, \(j_{\theta} = r_{2\theta}j\). So every element of \(D\) can be written uniquely in one of the following two forms.

- \(r_{\theta}, \theta \in [0, 2\pi]\)

- \(r_{\theta}j, \theta \in [0, 2\pi]\)

where

- \(r_{\theta + 2\pi n} = r_{\theta}\)

- \(r_{\alpha}r_{\beta} = r_{\alpha+\beta}\)

- \(r_{\alpha + \beta}\)

- \(j^2 = e\)

- \(jr_{\theta} = r_{\theta}^{-1}j\). (TODO: Show this using the previous rules)

This is a complete description of \(D\).

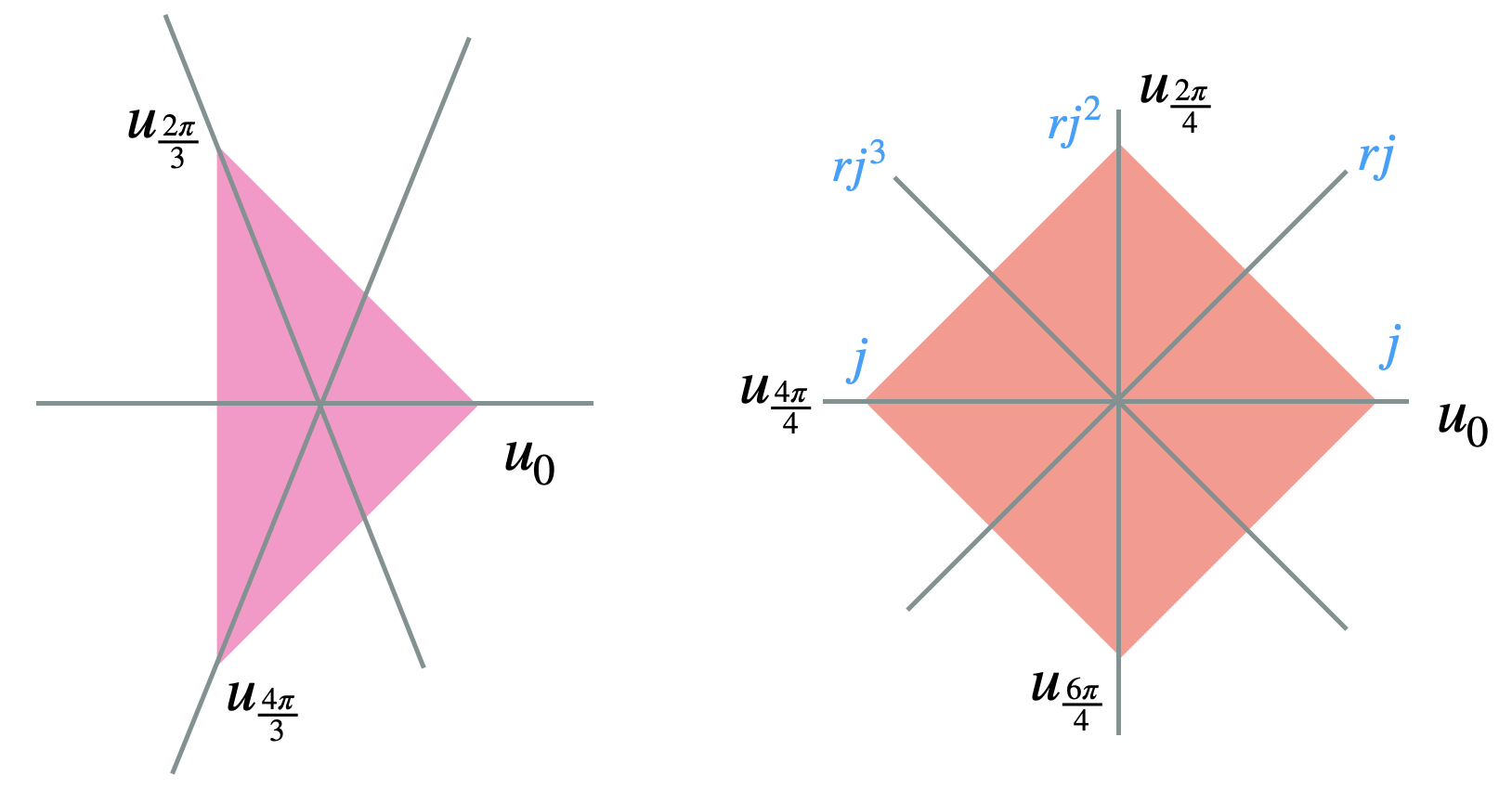

Dihedral Groups

Fix \(n \geq 3\). Let \(V = \{u_{\frac{2\pi}{n}k}, k = 0,...,n-1\}\) be the vertices of a regular \(n-\)gon. Note that \(D_n \leq D \leq SO(3)\). Now, the group \(D_n\) will include specifically the symmetries of the disk that take the vertices of the polygon to themselves or another vertex in the polygon. In \(D_n\),

Rotations in \(D_n\) are therefore: \(e, r, r^2, r^3, ..., r^{n-1}\) where \(r^{k+n} = r^k\).

Flips in \(D_n\) are \(j, rj, r^2,...,r^{n-1}j\) since we established that \(j_{\frac{\pi}{n}k} = r_{\frac{2\pi}{n}}j_0\). In general, we’ll have \(n\) flips for an \(n-\)polygon illustrated as follows

Note that \(D_n\) has \(2n\) symmetries total and we have the following identities:

- \(r^n = e\)

- \(j^2 = e\)

- \(jr = r^{-1}j\)

- \(j^2 = e\)

Notice also that this group is generated by two elements so \(D_n = \langle r, j\rangle\). Overall, you will see that

References

- MATH417 by Charles Rezk

- Algebra: Abstract and Concrete by Frederick M. Goodman