So how do you go about graphing a trigonometric function of the form,

Let’s study each coefficient and figure out what it does to the original graph and how it transforms it.

What Values Do We Plot?

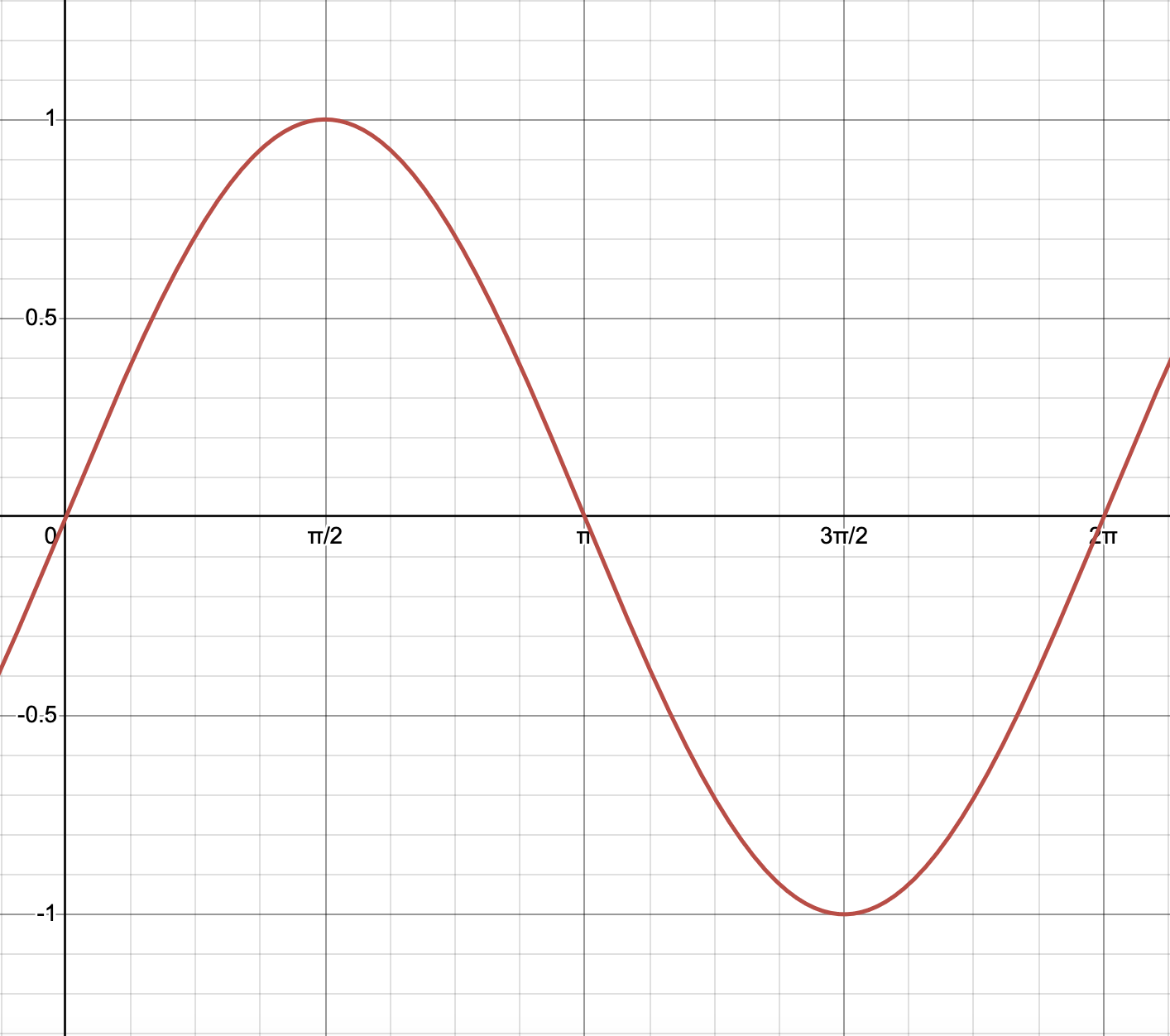

Before deciding on the values, we need to understand that both sine and cosine repeat their values at regular intervals or periods. The period of \(\sin(x)\) and \(\cos(x)\) is exactly \(2\pi\). So the sine or cosine wave will just repeat every \(2\pi\). This means we can just focus on plotting one single entire wave and then just repeat the rest.

What \(x\) values do we pick in the period \([0,2\pi]\)? For both sine and cosine, we typically choose the 5 critical value where we’re crossing the \(x\) axis (\(x\) intercept) or where we have a maximum or a minimum. For both sine and cosine, This happens at \(0, \pi/2, \pi, 2\pi/3\) and \(2\pi\). Sine has 3 zeros at \(0\), \(\pi\) and \(2\pi\). Cosine has two zeros at \(\pi/2\) and \(3\pi/2\). If we’re graphing \(\sin(x)\), then we’ll have the following table,

| x | 0 | \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) | \(\pi\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\) | \(2\pi\) |

| y | 0 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 0 |

This table will just repeat in the next period from \(2\pi\) to \(4\pi\) and so on.

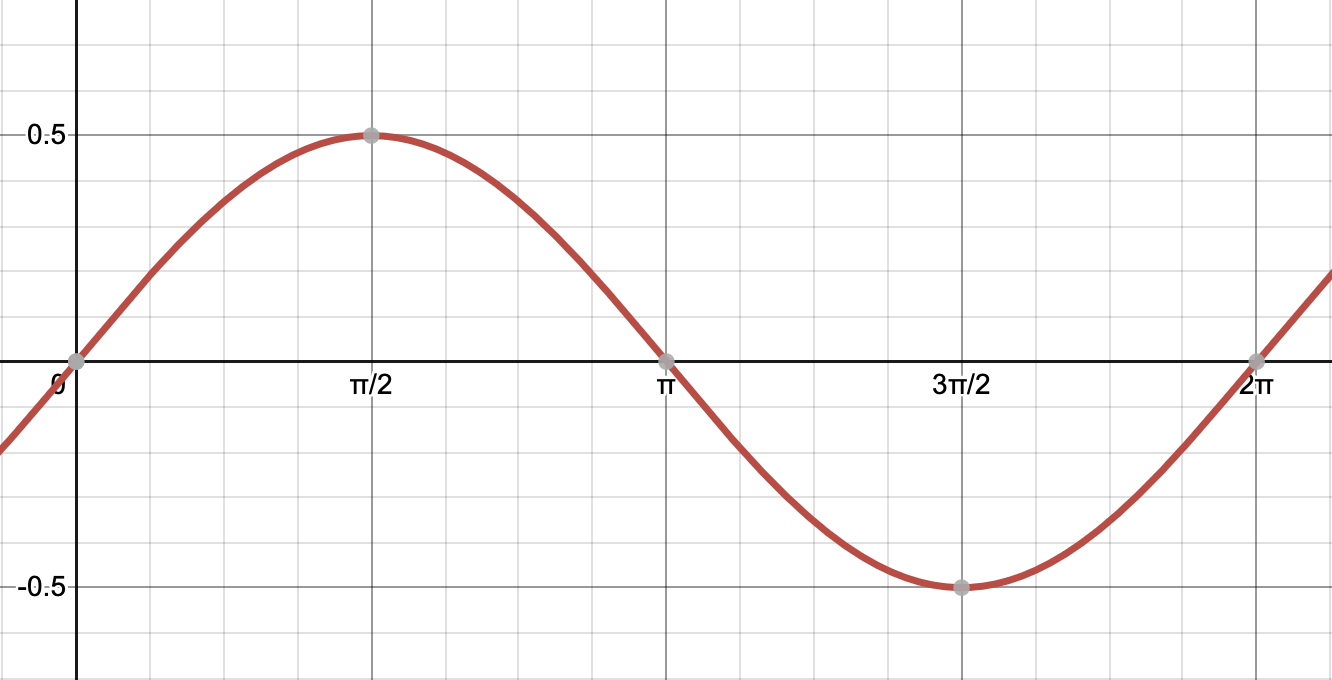

Amplitude

\(a\) is the amplitude. This indicates how far up and down the wave of sine or cosine would go. Say we’re given the function,

With the new amplitude, we’ll take the original \(y\) values and just multiply them by the amplitude. To do that, we can add two new rows to the table. Notice here that \(x\) doesn’t change since the amplitude doesn’t shift the graph in any way and the \(y\) values are just multiplied by the amplitude.

| x | 0 | \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) | \(\pi\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\) | \(2\pi\) |

| y | 0 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 0 |

| New x | 0 | \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) | \(\pi\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\) | \(2\pi\) |

| New y | 0 | .5 | 0 | -.5 | 0 |

and we’re done.

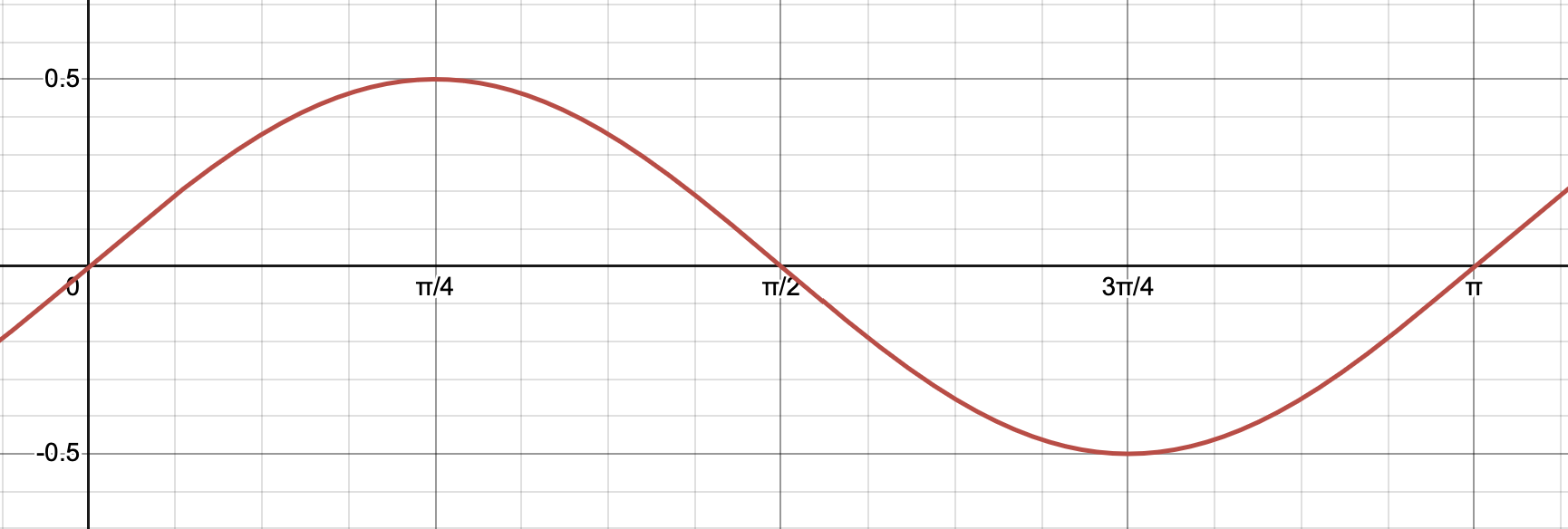

Period

We know both \(\sin(x)\) and \(\cos(x)\) have a period of \(2\pi\). Suppose we want to graph the following function,

To find the period we divide \(2\pi\) by \(2\) so the new period is now \(\pi\) instead of \(2\pi\). Why do we divide? This value 2 that is multiplied by \(x\) is squeezing our sine wave. If it was 0.5, then this will be a stretching factor and our period will stretch to become \(4\pi\).

The easiest way to graph this new function is to take the new period \(\pi\) and divide it into 5 sections. We can do so by dividing the period by 4 to figure out the distance between each section. Divide \(\pi\) by 4 to get \(\pi/4\). So now the first critical value will happen at 0. The next one will happen at \(0+\pi/4\). The one after will happen at \(0+\pi/4+\pi/4 = \pi/2\) and so on until we reach the fifth critical value at exactly \(\pi\).

| New \(x\) | 0 | \(\frac{\pi}{4}\) | \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{4}\) | \(\pi\) |

Let’s copy over the original values from the graph of \(\sin(x)\).

| \(x\) | 0 | \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) | \(\pi\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\) | \(2\pi\) |

| \(y\) | 0 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 0 |

| New x | 0 | \(\frac{\pi}{4}\) | \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{4}\) | \(\pi\) |

And then compute the new \(y\) values by multiplying by the amplitude

| \(x\) | 0 | \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) | \(\pi\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\) | \(2\pi\) |

| \(y\) | 0 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 0 |

| New \(x\) | 0 | \(\frac{\pi}{4}\) | \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{4}\) | \(\pi\) |

| New \(y\) | 0 | .5 | 0 | -.5 | 0 |

That’s it! We didn’t have to plug in any \(x\) values in the function and compute it. We just copied the \(y\) values we had. This works because we took the new period and determined first where the x-intercept will happen (we know with \(\sin(x)\) that it happens at 3 places (beginning, middle, end)). And then we determined where the peak and minimum will happen. This happens at the first and third quarter of the period. The reason why we do it this way is because often we’ll get the critical \(x\) values at positions where we don’t know off hand what the sine value would be (none of the famous angles we know). And if we don’t have a calculator then we’d be stuck so this is an easy way to avoid needing a calculator.

Horizontal Shift

Let’s now focus on the horizontal shift that could happen by having a term inside (not to be confused with the period). Here 2 is the period and \(-\pi/2\) is the shift.

What does this \(-\pi/2\) do?

First of all, we know the period is \(2\pi/2 = \pi\) from the last section and we know the \(x\) values of the new period will be,

| New \(x\) | 0 | \(\frac{\pi}{4}\) | \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{4}\) | \(\pi\) |

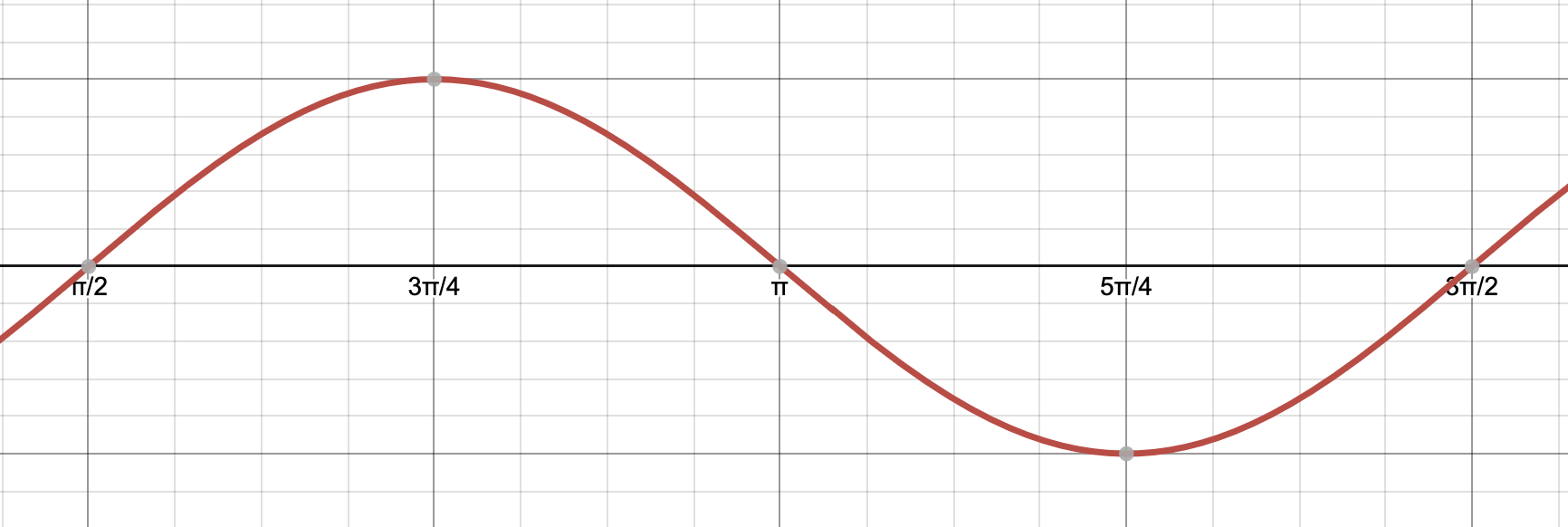

But now we also have a shifting factor of \(-\pi/2\). This factor shifts the graph to the right by \(\pi/2\) (Why to the right)? Now we’re going to start our period at \(\pi/2\) instead of 0 like we’re used to. So the whole row of \(x\) values we generated above weill need to get shifted by adding \(\pi/2\).

| New \(x\) | \(\pi/2\) | \(\frac{\pi}{4}+\frac{pi}{2} = \frac{3\pi}{4}\) | \(\frac{\pi}{2}+\frac{pi}{2} = \pi\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{4}+\frac{pi}{2} = \frac{7\pi}{4}\) | \(\pi + \frac{pi}{2} = \frac{3\pi}{2}\) |

Let’s copy over the original values from the graph of \(\sin(x)\).

| \(x\) | 0 | \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) | \(\pi\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\) | \(2\pi\) |

| \(y\) | 0 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 0 |

| New \(x\) | \(\pi/2\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{4}\) | \(\pi\) | \(\frac{7\pi}{4}\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\) |

Finally, let’s calculate the new \(y\) using the original values and multiplying then by the amplitude.

| \(x\) | 0 | \(\frac{\pi}{2}\) | \(\pi\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\) | \(2\pi\) |

| \(y\) | 0 | 1 | 0 | -1 | 0 |

| New \(x\) | \(\pi/2\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{4}\) | \(\pi\) | \(\frac{7\pi}{4}\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\) |

| New \(y\) | 0 | .5 | 0 | -.5 | 0 |

Vertical Shift

The last thing we want to know is how to apply the vertical shift. What we want to do is take our x-axis and pretend to lift it either up or down depending on the vertical shift we have. So if we’re graphing something like

Then this means that we are shifting up the graph by 1 point. So we’ll take that row of \(y\) values and add 1 everywhere. The \(x\) values will remain the same from the last section.

| \(x\) | \(\pi/2\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{4}\) | \(\pi\) | \(\frac{7\pi}{4}\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\) |

| \(y\) | 0 | .5 | 0 | -.5 | 0 |

| New \(x\) | \(\pi/2\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{4}\) | \(\pi\) | \(\frac{7\pi}{4}\) | \(\frac{3\pi}{2}\) |

| New \(y\) | 1 | 1.5 | 1 | 0.5 | 1 |

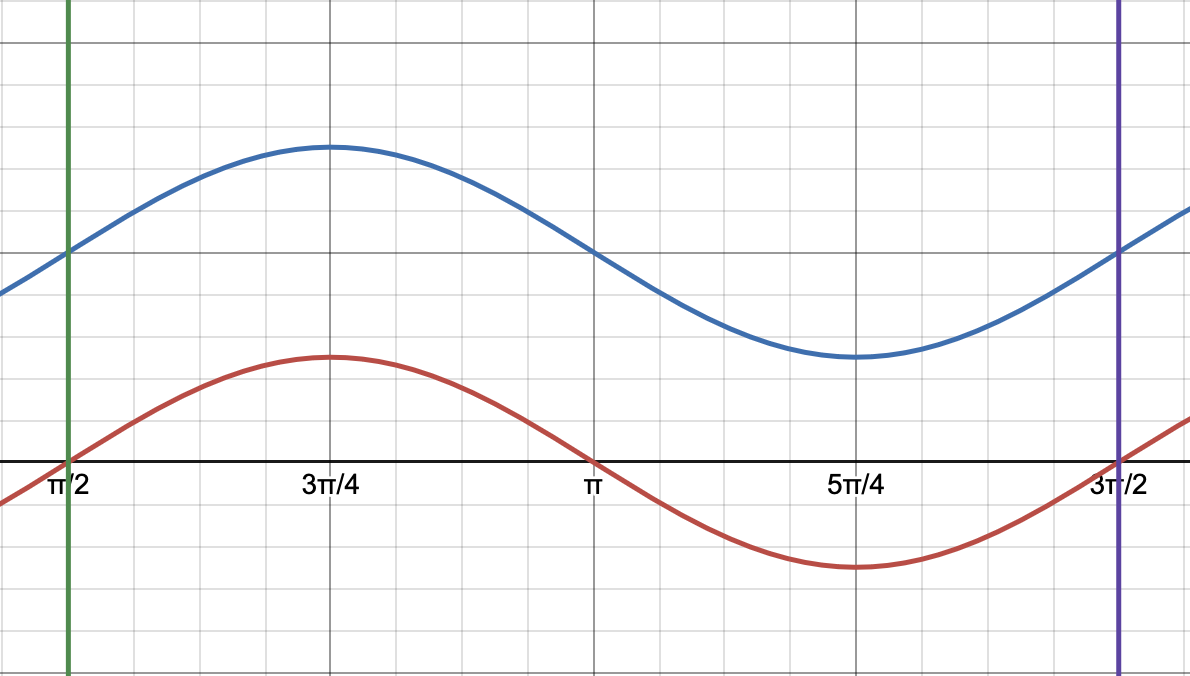

So you can see here the red graph from the last section and now it’s shifted up by 1 point!