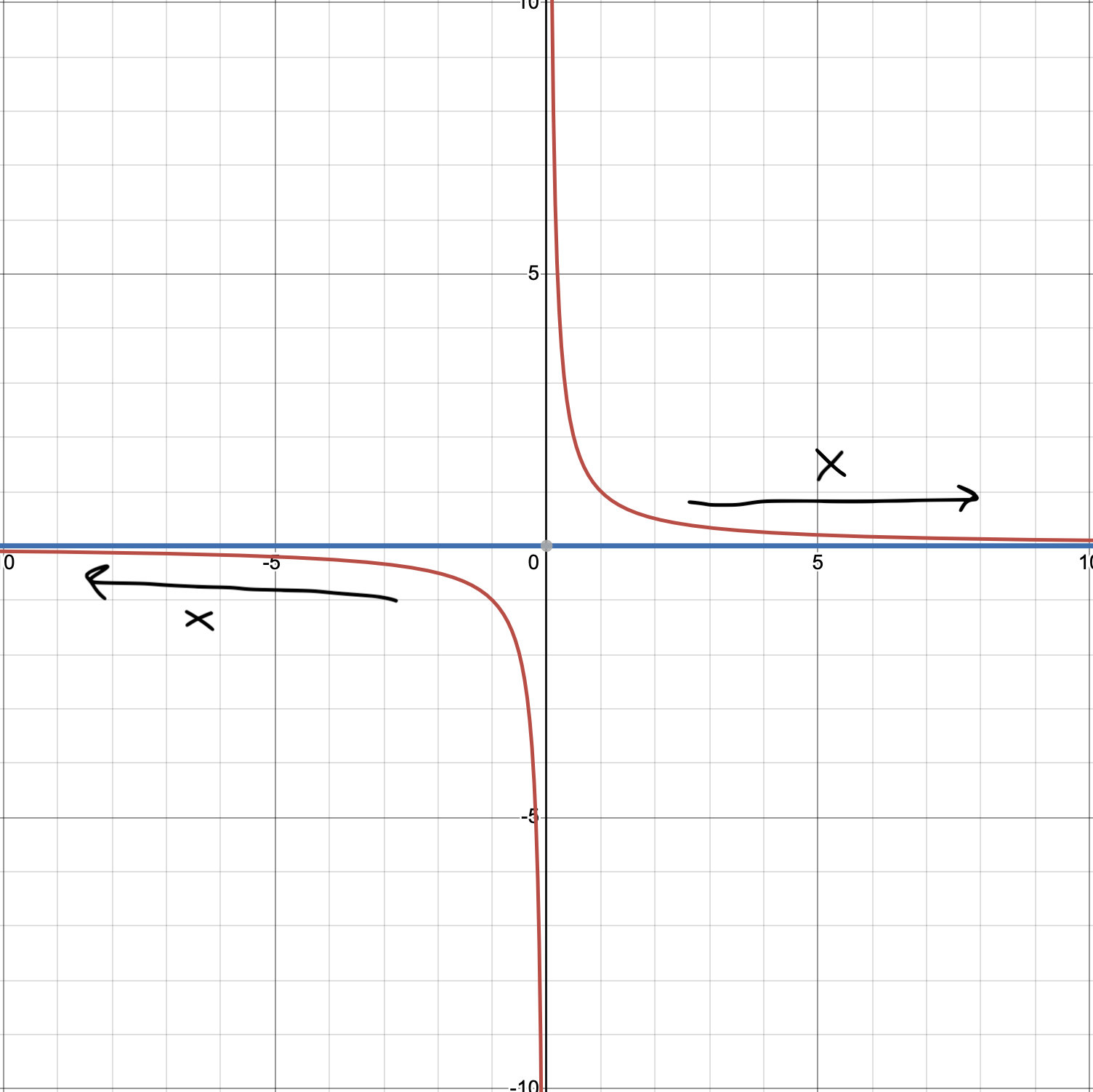

Given some function \(f\). A horizontal asymptote is a line \(y=a\) where as the input \(x\) to the function approaches negative or positive infinity, we will find that \(f(x)\) will approach \(b\). (So just the opposite of vertical asymptotes where as \(x\) approaches \(a\), we will approach positive or negative infinity. For example, for \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x}\), as we plug in very large values of \(x\) (whether positive or negative), we will notice that \(f(x)\) will get closer to zero! So the line \(y=0\) is a horizontal asymptote for the graph of the function \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x}\).

Finding a Horizontal Asymptote

The end behavior of a rational function is determined by the leading terms in the numerator and the denominator. Intuitively this makes total sense because as we plug in really large values of \(x\), the leading term will be the only thing matters. Because of this, we want to focus on only these leading terms. For example if we have,

Then we’ll want to study,

The degree of the numerator is \(m\) and the degree of the denominator is \(n\). Horizontal asymptotes occur only when \(m \leq n\).

Case 1: $$m < n$$

What happens to the rational when the degree of the numerator is less than the degree of denominator. Take the example of \(1/x\) again. We have degree 0 in the numerator and degree 1 in the denominator. You can see here as that as you plug in larger and larger values of \(x\), the function will approach zero. Similarly take the function,

The degree of the numerator is 2 while the degree of the denominator is 5. Let’s focus on each leading term

We can see here that it simplified again to a constant up in the numerator. Again, as \(x\) gets larger, we will approach zero. This is the reason why the rule simply states that if \(m < n\), then the horizontal asymptote will always be at \(y=0\).

Case 2: $$m = n$$

To study the behavior of a rational function when \(m = n\), we will again focus on the leading terms in the numerator and the denominator. For example, if we have

then we’ll focus on,

This simply states that as we plug in larger and larger values of \(x\), we will notice that our function is approaching the line \(y = 2\). Hence the rule states that the horizontal asymptote for when \(m = n\), is the leading coefficient of the numerator divided by the leading coefficient of the denominator.

Can you cross a horizontal asymptote?

Yes! unlike vertical asymptotes, we can cross horizontal asymptotes.

References: