Given some function \(f\). A vertical asymptote is a line \(x=a\) where as the input \(x\) to the function approaches \(a\), \(f(x)\) will approach either positive or negative infinity.

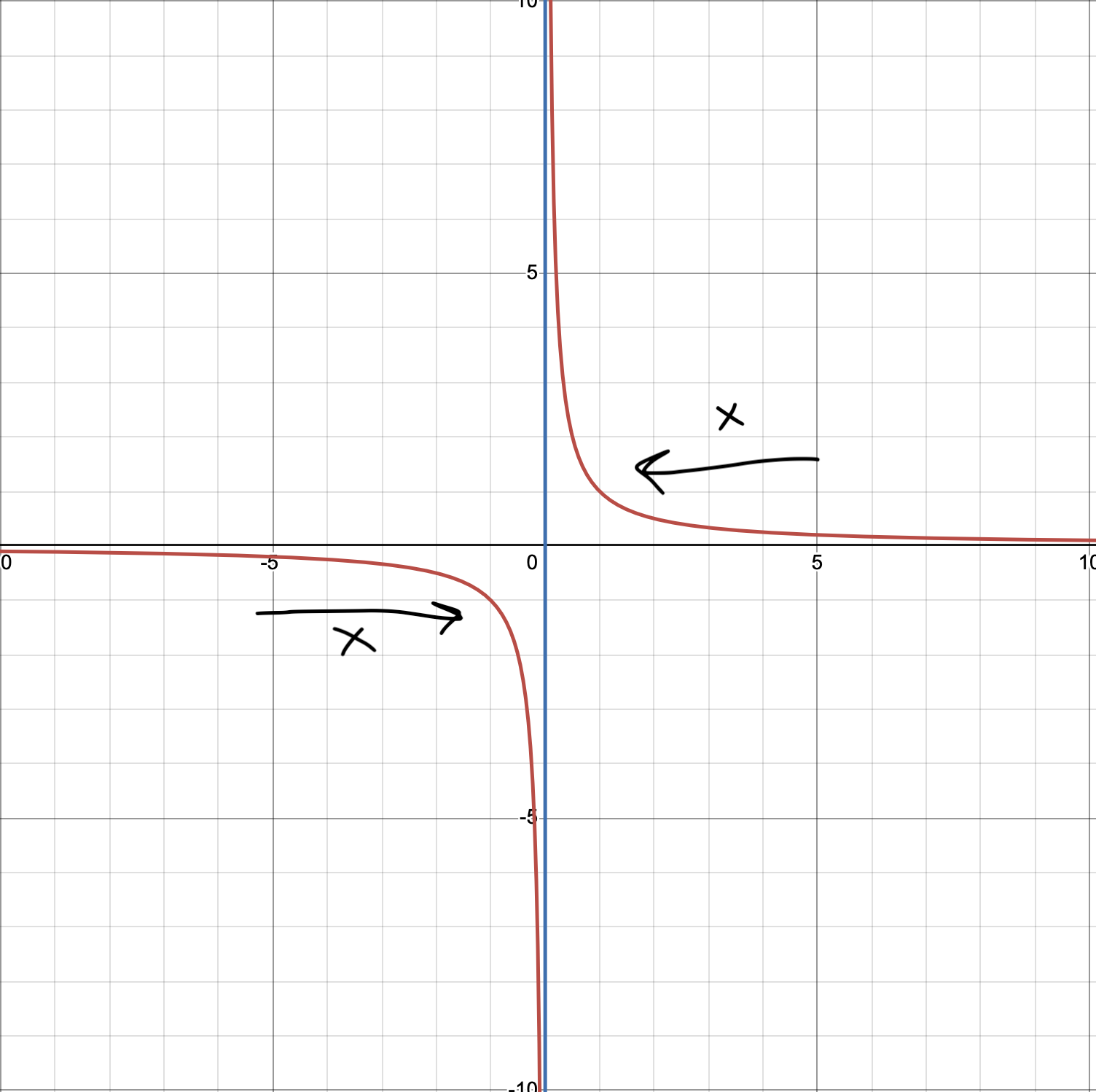

For example take the function \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x}\) graphed above. \(f(0.1) = 10\), \(f(0.01) = 100\) and \(f(0.000001) = 1000000\). We notice here that as \(x\) approaches 0, \(f(x)\) gets really large and approaches positive infinity. Similarly, as \(x\) approaches zero coming from the negative side of the number line, it approaches negative infinity. \(f(-0.000001) = -1,000,000\) and so on.

So the line \(x=0\) is a vertical asymptote for the graph of the function \(f(x)=\frac{1}{x}\).

Finding a Vertical Asymptote

A vertical asymptote occurs when the function \(f\) has “domain issues”, meaning that for some input \(b\), the denominator becomes zero and so we can’t really plug this value in \(f\) and we typically recognize that by excluding \(b\) from the domain of \(f\). When graphing \(f\) however, we’ll have two cases. This problematic \(b\) can either create a vertical asymptote at \(x=b\) or just a hole in the graph.

For example in the example of \(1/x\) (graphed above), \(x = 0\) is not in the domain of \(f\). Here \(x = 0\) is a vertical asymptote rather than a hole in the graph.

Holes vs. Vertical Asymptotes

When does the problematic value \(x=b\) create a hole instead of a vertical asymptote? This happens when we have a mutual factor between the denominator and the numerator that can cancel each other. Usually this is denoted with a hole in the graph of the function at \(x = 0\). For example let \(g\) be,

We can see here that at \(x = -7\), we do have a vertical asymptote. But at \(x = 3\), we just have a hole in the graph of \(g\). It’s really important here to note that both \(\frac{(x-3)(x+3)}{(x-3)(x+7)}\) and \(\frac{(x+3)}{(x+7)}\) have the same graph except that the first one will have a hole at \(x=3\) since the domain says it’s undefined there.

Vertical Asymptotes vs. Horizontal Asymptotes

One other thing to note about vertical asymptotes (vs. horizontal asymptotes for example) is that the input \(x\) will only ever approach \(b\) but never ever cross the vertical asymptote at \(x=b\). Because we can’t evaluate \(x\) at \(b\). \(b\) is not in the domain of \(f\)! (unlike horizontal asymptotes for example where crossing is a possibility depending on some factors).

Multiplicity of Vertical Asymptotes

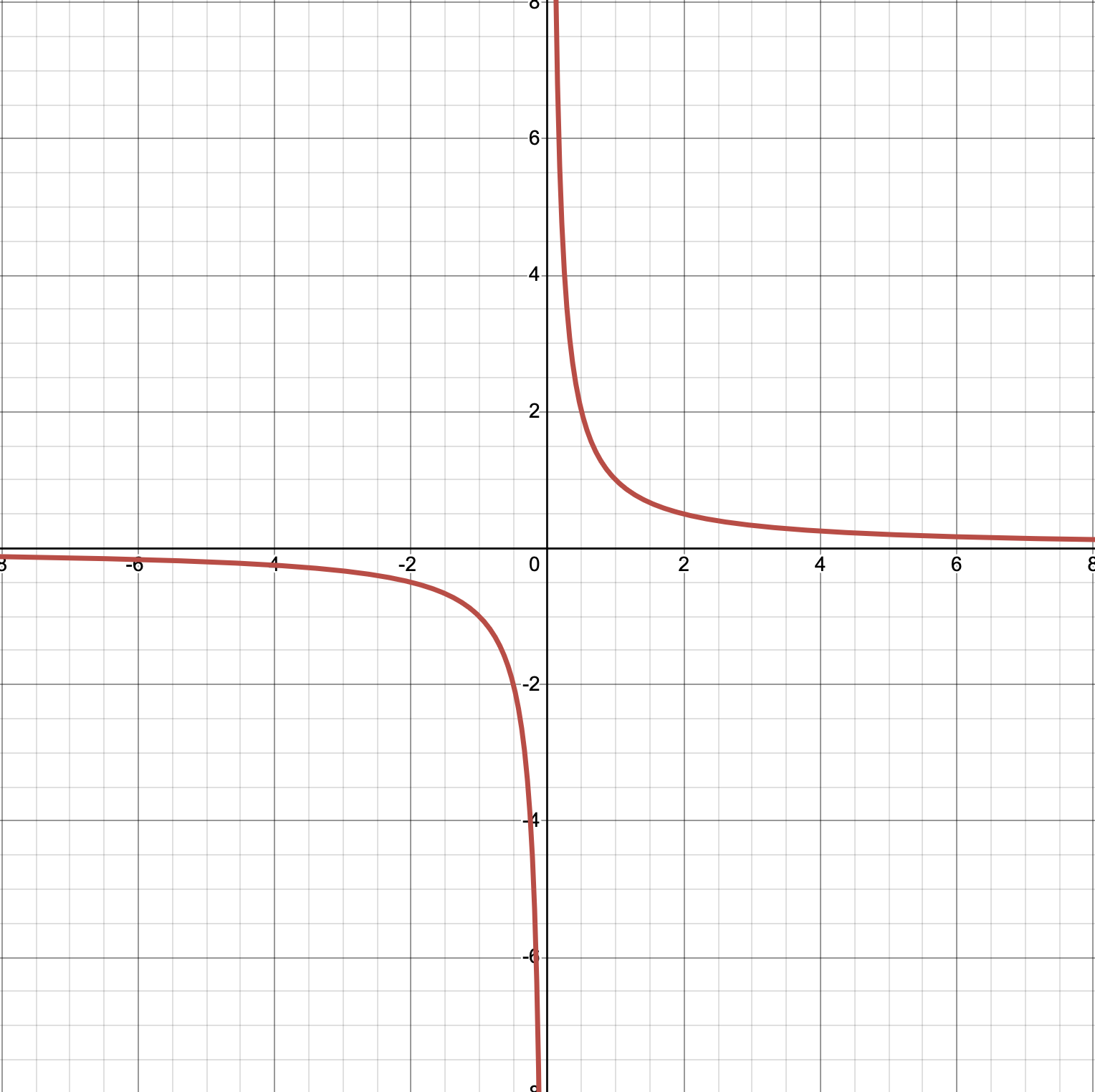

Another important property of vertical asymptotes is that the multiplicity of the factor in the denominator will affect how the graph is shaped. For example. if we’re graphing \(1/x\), then we have only one factor of \(x\) which means we have an odd multiplicity. This will result in the following graph where on one side of the vertical asymptote \(x=0\), \(x\) approaches positive infinity and on the other side of the vertical asymptote, \(x\) is approaching negative infinity.

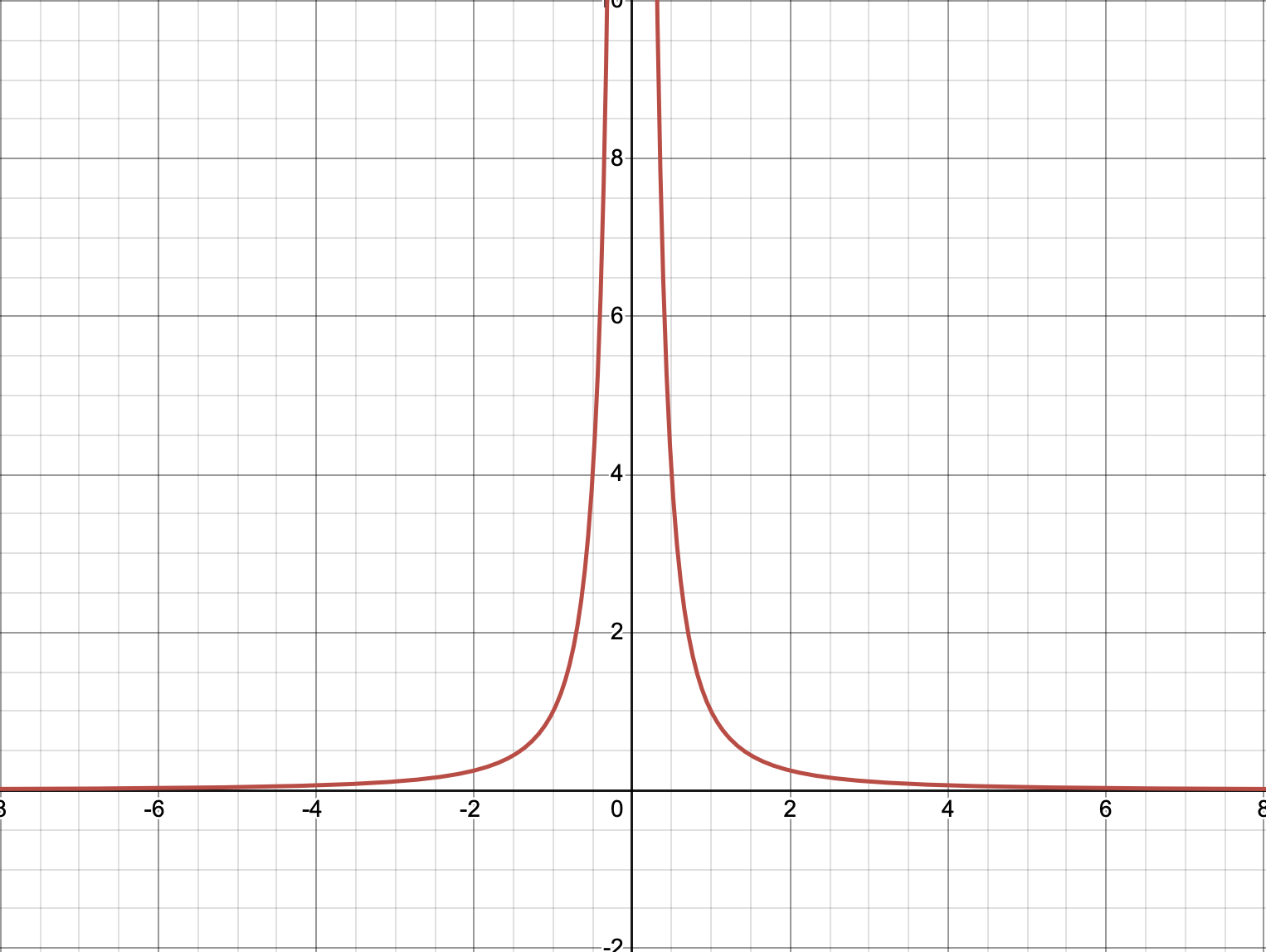

If instead we were graphing a function like \(f = 1/x^2\) where now the multiplicity of the factor is even, then we’ll see that on either side of the vertical asymptote, we’re approaching the same positive infinity.

References: