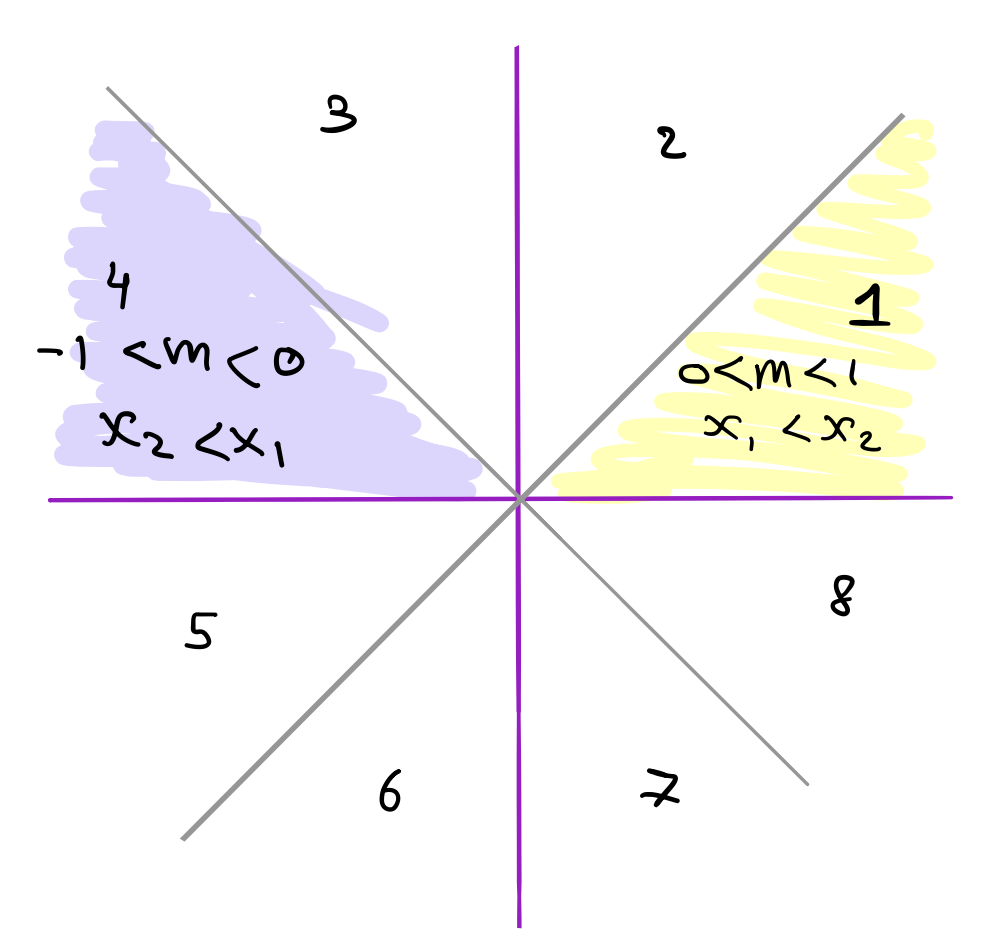

I’m going to write my notes here while learning the Bresenham’s line drawing algorithm from the two sources I’ve listed at the bottom of the page. We want to draw on screen the line given by the two points \((x_1,y_1)\) and \((x_2,y_2)\). To simplify things, we will restrict ourselves to positive slopes that are less than 1 and so \(m = \Delta y/\Delta x < 1\). Therefore \(\Delta x > \Delta y\). For this reason, we’re going to step in the right direction from \(x_1\) to \(x_2\) since we have more steps in \(x\) than in \(y\).

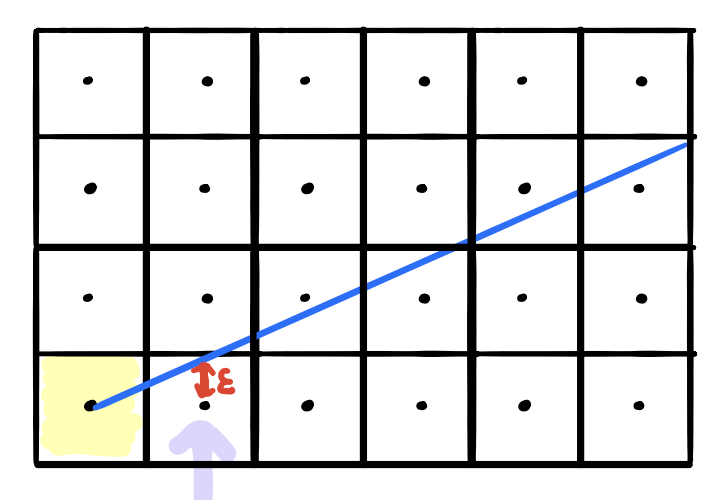

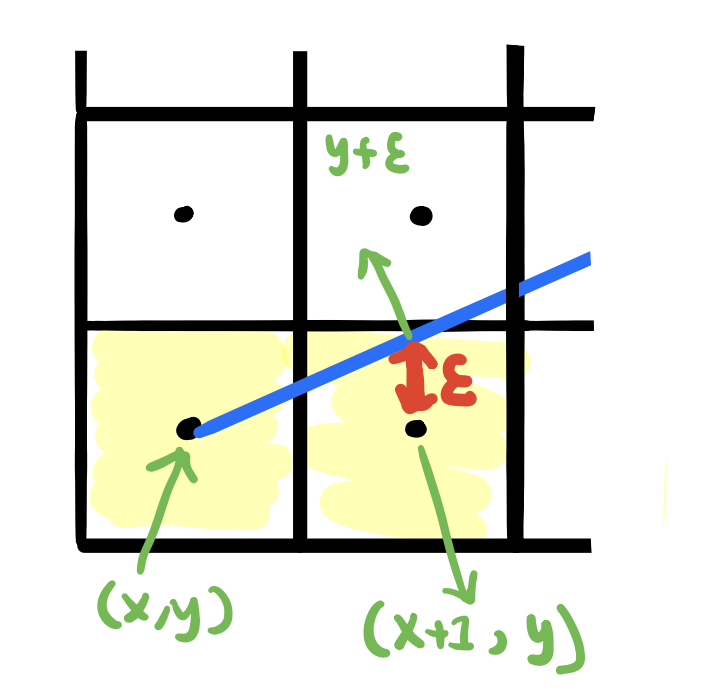

We’re going to start by the drawing the very first point at \((x,y)=(x_1,y_1)\). Next we’re going to move right to to \(x+1\) (We will always move in \(x\) in each iteration and so we’ll have two choices for which point to draw. It will either be the point \((x+1,y)\) or the point \((x+1,y+1)\)). As we keep moving in the x-direction, we’ll accumulate the error in the y direction in a new variable \(\epsilon\).

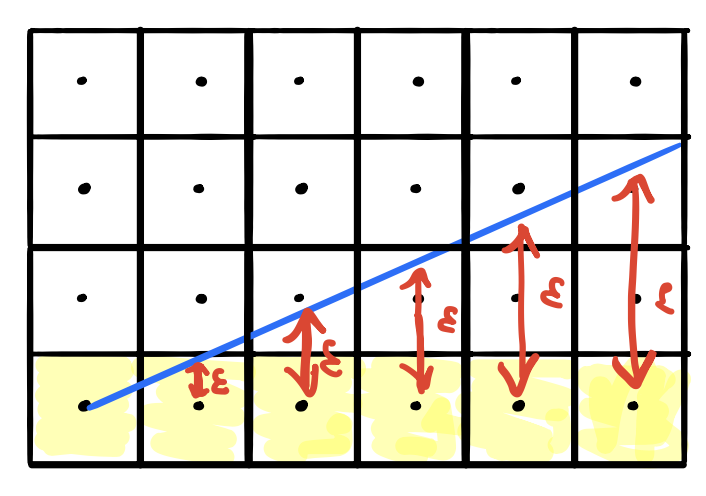

Notice above that if we always draw the point \((x+1,y)\) and never do anything with the y-coordinate, then we’ll draw the shaded yellow points above while our error term will just keep increasing forever. We don’t want that. What should the error term be then? Let’s zoom in at the first case when we draw the point \((x+1,y)\).

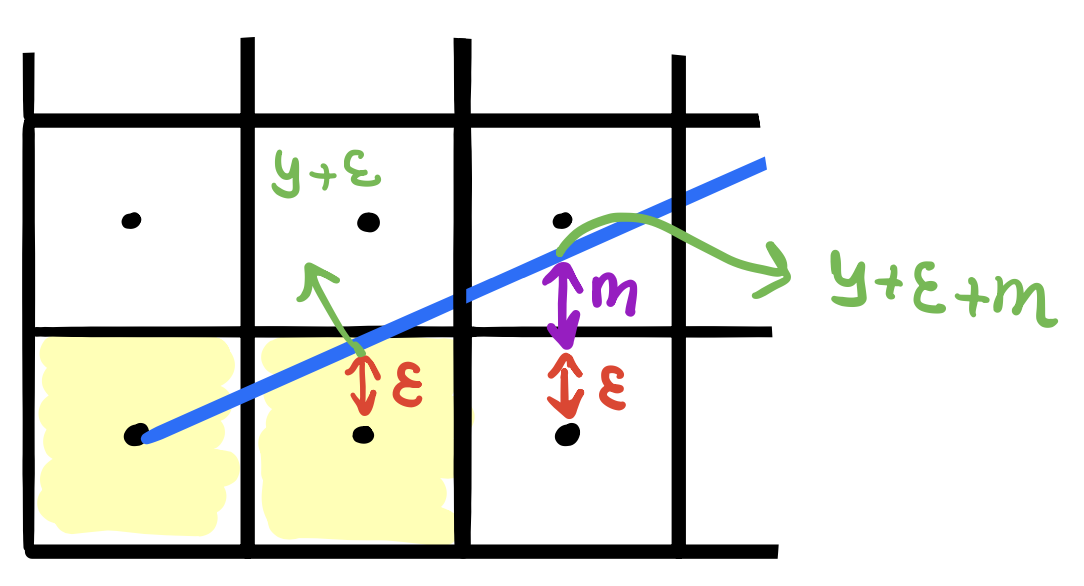

Notice here, that \(y\) on the line is really the \(y\) that we drew plus the error term that we want to keep track of. Moreover, recall that the slope is just \(\Delta y/\Delta x\). \(\Delta x\) is 1 here since we moved from x to \(x+1\). So \(m=(y+\epsilon-y)/1=\epsilon\). This means that we can just add \(m\) to the error term as move in the right direction! We will decide whether to move up to \(y+1\) versus stay on \(y\) if the error term is greater that 0.5. Suppose now, the error is actually greater than 0.5 and we moved \(y\) one step up, how should be adjust the error term?

As before, we first (always) move one step forward in the \(x\) direction. We add \(m\) to our error term like we explained in the previous paragraph. Now the error term is greater than \(0.5\). We move in the \(y\) direction one step. Notice here that the error term is now decreased by 1 since we moved one step up. So we just decrement \(\epsilon\) by 1. The overall procedure will be:

void draw_line(x1, y1, x2, y2) {

dx = x2 - x1, dy = y2 - y1

m = dy/dx

x = x1, y = y1

eps = 0

while (x < x2)

draw_point(x,y)

eps += m

if (eps > 0.5) {

// error is too big so move up in the y direction

y++

eps -= 1 // take 1 from the error term

}

x++ // we always move 1 step right in each iteration

}

}

Integers Only!

The above procedure works really well but we don’t want floats. We want integers only. What can we do to avoid calculating the slope \(m\). In every iteration, notice that we’re adding \(m\) to \(\epsilon\) and then directly comparing it again the threshold \(0.5\). Let’s expand the terms and see where we can go.

where \(\epsilon' = \Delta x\epsilon\) above. So when we first update the error to add \(m\) to it. Instead of adding \(m\), we will add \(\Delta y\). To see why let’s expand the term again.

And when we decrement 1, we can do the same and expand to see.

Here is the procedure again with the lines changed marked with “CHANGED”.

void draw_line(x1, y1, x2, y2) {

dx = x2 - x1, dy = y2 - y1

m = dy/dx

x = x1, y = y1

eps = 0

while (x < x2)

draw_point(x,y)

eps += dy // CHANGED

if (2*eps > dx) { // CHANGED

// error is too big so move up in the y direction

y++

eps -= dx // CHANGED

}

x++ // we always move 1 step right in each iteration

}

}

Generalizing The Algorithm

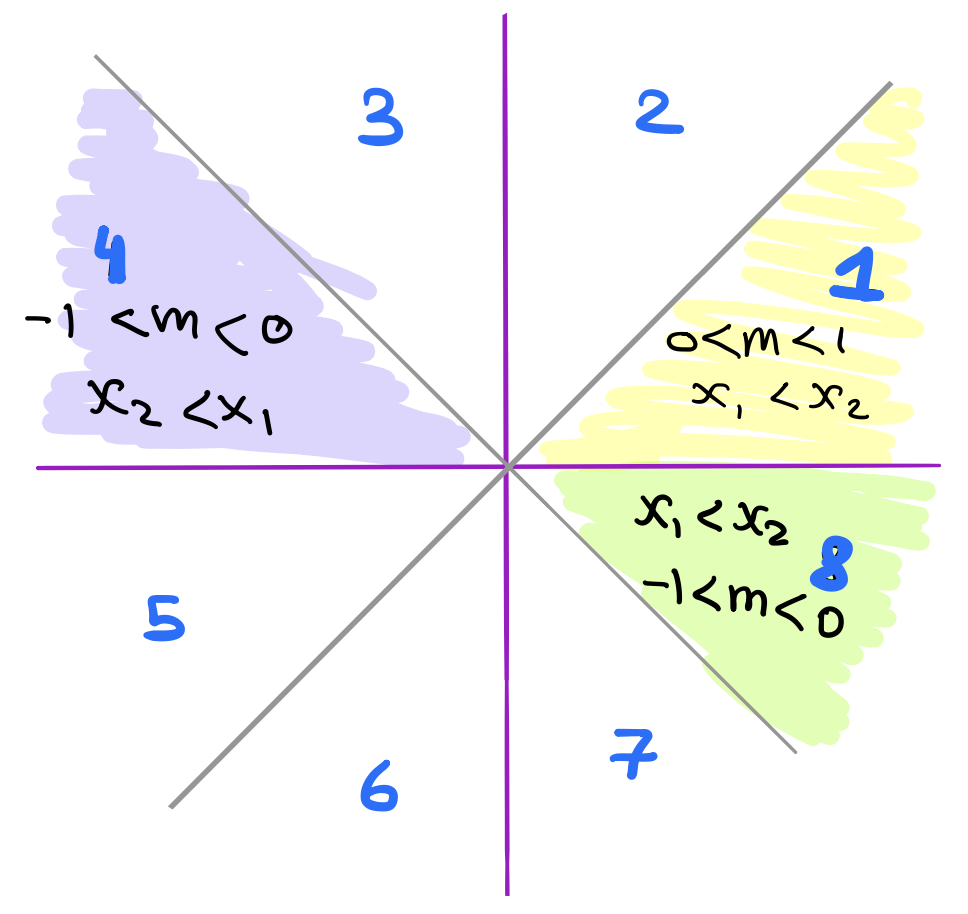

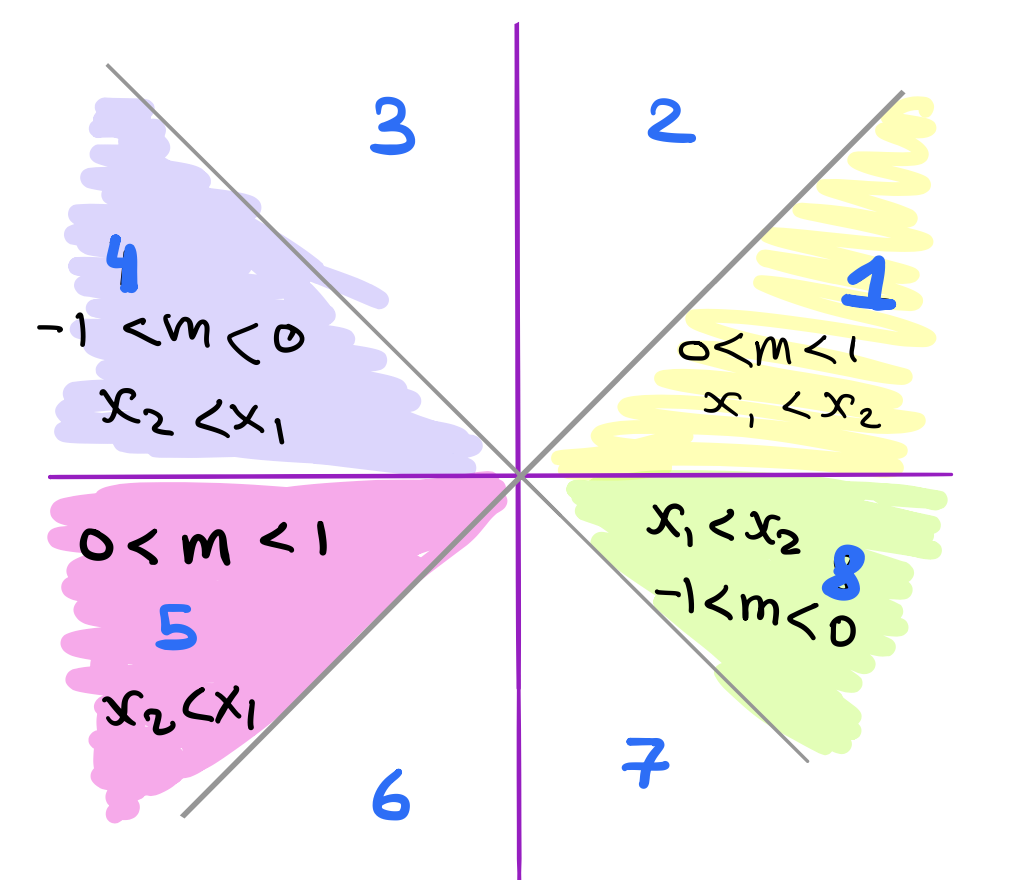

So far we have code that works for the first octant ONLY! where the slope is positive and is less than 1. How do we handle the other cases? We’re going to handle the case when the \(\Delta x\) is still larger in magnitude than \(\Delta y\).

Let’s start with the fourth octant. Here \(|m| < 1\) but \(x_1\) is greater than \(x_2\). This shouldn’t be too bad right? While we draw we’re going to decrement \(x\) in each iteration (instead of incrementing). This can be easily done if we introduce a variable xstep and make it equal to -1 whenever \(x_1 > x_2\). Additionally, we will need to flip the sign of \(\Delta x\) to be positive again. This way the slope is positive and we can use the same exact code for the first octant.

For the fifth octant. This time \(\Delta y\) is negative so we want to flip that and also move \(y\) down instead of up. So we’ll introduce a variable \(ystep\) and set it to -1 whenever \(y_1 > y_2\). Notice here that \(\Delta x\) is still larger than \(\Delta x\). So the same exact code still works!

What about the eigth octant? The magnitude of the slope is still between 0 and 1. But now we have both \(\Delta x\) and \(\Delta y\) negative. We just need to flip these! along with making \(xstep\) and \(ystep\) both be -1.

Next, we’ll handle all the remaining octants where the magnitude of the slope is greater than 1. Here we have more steps in \(y\) than in \(x\). So we need instead to move in the \(y\) direction while keeping the error term to track the error in \(x\) instead of \(y\). So the same exact code still but we just need to swap \(x\) and \(y\)! of course we will still need to adjust value of xstep and ystep similar to the above cases that we discussed.