Note

These are my rough notes based on attending CS148. They might contain errors so proceed with caution!

Overview

So now the focus will be on formalizing why the $\cos(\theta)$ matters. To do this, we’ll study two important things about light. How does light leave the light source and how does it hit an object?

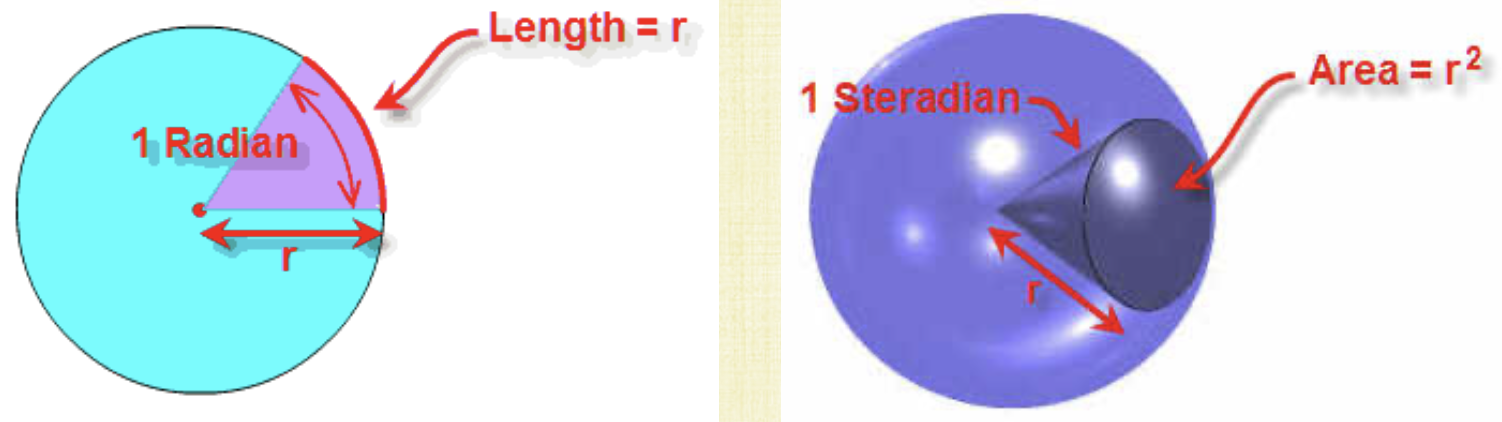

To start, we’ll want to know how to measure an angle in 3D. For a 2D circle, we have

where $l$ is the length of the arc. We know the circumference is $2\pi r$ and so we’ll have $2\pi r/r = 2\pi$ total radians. The same can be extended to a sphere, we have (TODO: Find a tutorial on solid angles!)

This time, $A$ is the area of the surface on the sphere. The surface area of a sphere is $4\pi r^2$ so a sphere has $4\pi$ steradians$$. We want to know how many photons in this cone are coming out. This will tell us how much light power is coming out. Note here that if the cone gets bigger, the amount of photons is not changing. The photons are just spreading farther. At any cross section of that cone, we’ll have the same amount of photons.

(1) Radiant Intensity from a Light Source

How does light leave a light source? The radiant intensity from a light source is

$\phi$ is the light source power (in watts = joules per second) or the amount of photons. $\omega$ is a solid angle from the previous section. So this is photons per solid angle. The intensity is stronger when a lot of photos are coming out of that cone. So again, we don’t measure or care about the amount photons coming out of the light. We instead measure the photons per solid angle ($\omega$). This is what matters.

For isotropic light sources, we have the same amount of photos going out in each direction, So we don’t depend on omega anymore. $I$ is just a constant. So we can just bring the $I$ out below and take the integral to find $\phi$. We know from the previous section that the sphere has $4\pi$ steradians and so we’ll end up with,

So if we know the power in watts of the light source ($\phi$), then we can divide it by $4 \pi$ to get $I$ (the radiant intensity). However for anistrophic light source, the intensity will vary. We have different amount of photons going in different directions so the intensity $I$ varies across the light as a function of $\omega$.

(2) Irradiance onto a Surface

So this is how the light leaves the light source. Now we’ll switch to surfaces! How does light hit an object? For lights, it’s like a point throwing out light. For surfaces, it’s some flat object with area catching this light. So instead of radiance intensity, we’ll define irradiance for surfaces,

So the irradiance is the amount of photos per surface area.

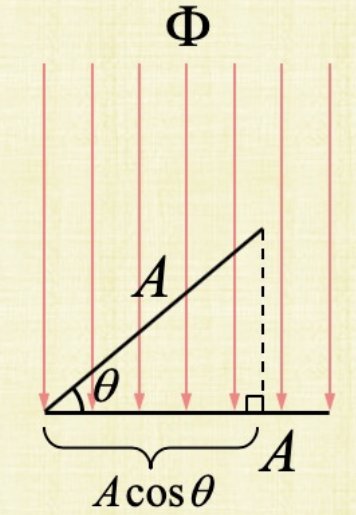

When the surface is flat, the irradiance is just the amount of photons divided by the surface area we’ll have:

Now take that bottom flat area and tilt it by an angle $\theta$. So now notice still in the above figure that when we tilt the area, that last bunch of photons (last two red rays) now miss that surface. How do we figure out how much we’re going to miss. We need to project that area to see that the new area is only $A\cos(\theta)$. So now if we divide this portion by $A$, this will be the fraction of photons that will hit the titled area. Take the formula above and multiply the number of photons by the fraction $A\cos(\theta/A$ to find the irradiance for the tilted area.

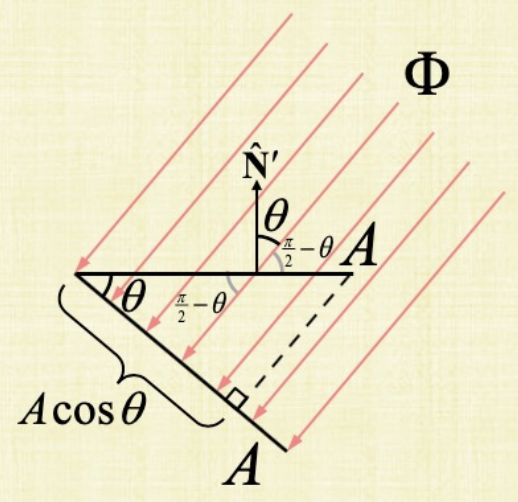

So basically, irradiance decreases as you tilt the surface since less photons hit per unit surface area. Now, we don’t really tilt objects. Instead the whole picture is rotated. This is what we typically see where the light is at an angle. That flat surface is still the same and the math still works out! why?

Why does the math still work out? It turns out that the angle in the above picure between the normal and the surface is the SAME angle that we computed above. So now what we can do is take the dot product of the light and the normal to get that SAME $\theta$ that measure how much “fewer” photons we’re going to get with the tilt! THIS IS SO FREAKING AMAZING!

Solid Angle vs. Cross Sectional Area

So now we’ll tie (1) radiance and (2) Irradiance together.

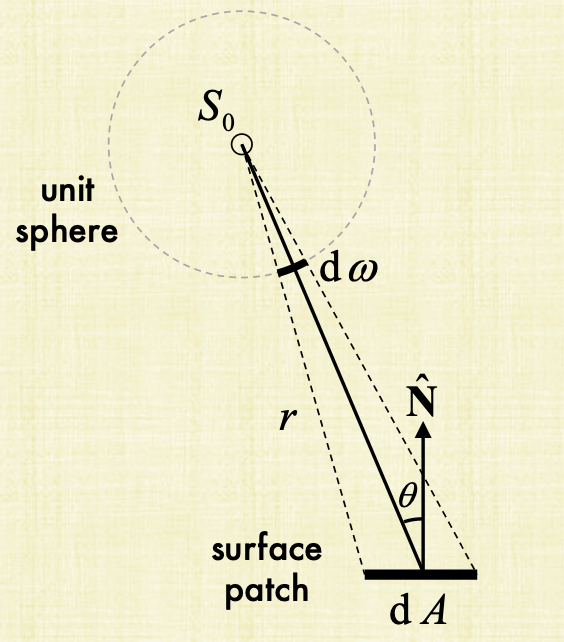

In this figure, the light source is at $S_0$. The surface is denoted by $dA$ above. The light comes out of this unit sphere. These photons start spreading out until they hit the surface patch in the figure above. We already know from the first section how to compute the solid angle using:

So now in the figure above, tilt that area so it’s orthogonal to the line coming out of $S_0$. This $dA$ area now is really the sphere surface area with radius $r$. (just draw a huge circle to incapsulate the whole region). This tilt if you remember is just $A\cos \theta$ from the previous section. So now substitute back to get

So what did we do here? We wrote an equation that compares the area of the object that the light is hitting to the steradians on the surface of the sphere where the light is leaving the light source from. This relationship is defined now by $r^2$ and $\cos(\theta)$. More tilt, means less light and more distance means also less light. This also implies the conservation of light energy. The amount leaving the cone, is captured by the area. To summarize, now we related the the amount of photons leaving the light to area of the surface we’re trying to shade.the solid angle varies with the distance and the tilt angle

Area Lights

But … light however doesn’t work as a single point. Light power is emitted per unit area. The emitted light goes in varius directions (area or sphere emitting in every direction). So how do we measure this? We break this light area into small area chunks (so radiant intensity per area chunk), So now we know the radiant intensity unit and we know the area chance unit and we can write the “Radiant Intensity per Area Chunk (aka Radiance)) as a fraction,

In graphics, we don’t care about the radiant intensity. We care about the radiance. So now we have both radiance and irradiance for surfaces capturing the light. Moreover, remember that the radiant intensity from a few slides ago is $d\phi/d\omega$ and that the irradiance is $E = d\phi /dA$. So substitute to see

This theta is the light theta. As you tilt the light source, you will get fewer photons just like when we titled the surface earlier. But this theta is the light source theta. So to summarize, we have two $\theta$s. One will affect how much light is coming out and one affects how much light is getting captured.

Remember this is not a point. It’s an area. So now this area can be tilted and the tilt angle is this new light theta that we’re seeing for the first time in this slide.

References

Fundamentals of Computer Graphics, 4th Edition

CS148 Lectures