Note

These are my rough notes based on attending CS148. They might contain errors so proceed with caution!

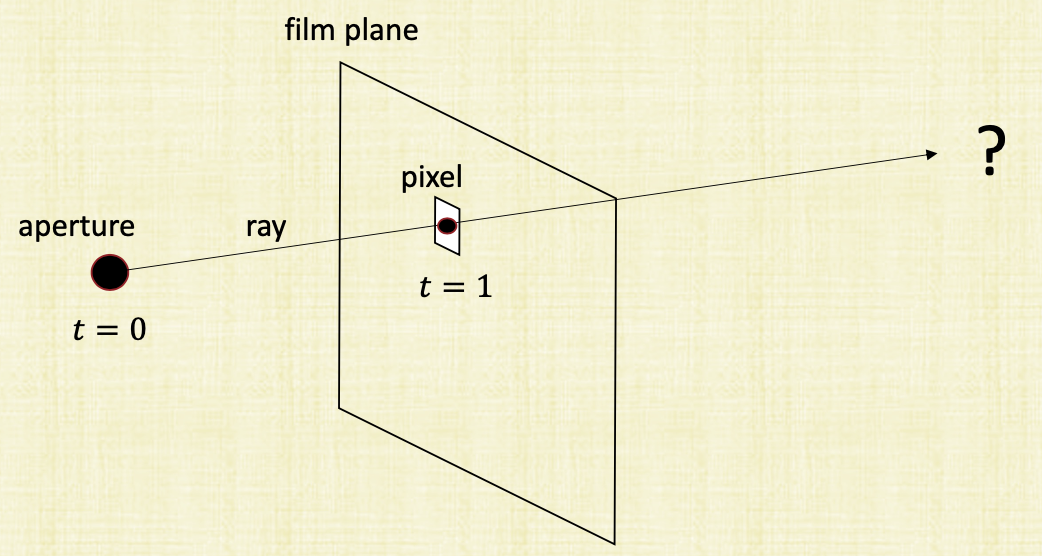

Constructing Rays

For each pixel, we create a ray. Its first intersection is used to determine the color of the pixel. The ray can be written as,

where $A$ is the aperture and $P$ is the pixel location. The ray is defined by $t \in [0, \infty]$. But for the figure above, what we care about is the first intersection where $t \geq 1$ since that’s what’s inside the viewing frustum.

Parallelization

- Scanline rendering is a per triangle operation but ray tracing here is a per pixel operation so it’s easy to parallelize it. For scanline rendering, the parallelization is done for each triangle.

- It’s easier to parallelize ray tracing on the CPU rathar than the GPU and it’s easier to parallelize scanline rendering on the GPU rather than the CPU.

- Memory coherency is important when distributing rays to threads/processors. We need to assign spatially neighboring rays to the same core. These rays will tend to intersect the same objects and therefore access the same memory.

Ray-Triangle Intersection

- The main operation in scanline rendering is to know if a pixel is inside a triangle in screen space fast. The main operation in ray tracing is figuring out if the ray intersect triangles in the virtual world fast (world space).

- In scanline rendering, we had to figure out how to calculate the barycentric coordinates fast (we saw many ways to do this and saw how they must all be between 0 and 1 and sum to 1, not to be outside the triangle for example) in order to determine if a pixel is inside a triangle. In ray tracing, now we have a triangle that we want to test in world space. Moreover, if we intersect a triangle, we still want to test and see if there are other triangles that we can intersect and are closer.

Three Options for Ray-Triangle Intersection

How do we speed up ray-triangle intersection? There are three options.

- One main idea to speed up the intersection here is that triangles are planar so we can do a ray-plane intersection to determine quickly if the pixel itersects the plane. If it does, then now we know the point is on the plane. Next we need to determine if this point is inside the triangle. Two ways to do this.

- Project this triangle to 2D since we don’t need the 3rd coordinate. We know the point is on the same plane as the triangle. How do we do this? By merely dropping a coordinate. Which coordinate? We want to drop the coordinate with the largest component in the triangle’s normal. This is because we want to the triangle with the maximal area in order to avoid errors. Once done, we can use the same “inside triangle” test from scanline rendering.

- Another option is directly do the point in triangle test in 3 dimensions. This isn’t hard to do. We just need to compute the normals differently and then do our check to see if the point is on the inside of all three rays.

- The third option to forget ray-plane intersection and directly compute the ray-triangle directly. This is similar to how ray tracing works for non-triangle geometry

Option 1: Ray-Plane Intersection

Given a ray and a plane. How can we determine if the ray intersects the plane?

- A plane is defined by a point $p_0$ and a normal direction $N$ (easily computed by the cross product of two edges).

- A point $p$ is on the plane if $(p - p_0) \cdot N = 0$. Therefore, if we want to find if a ray $R(t)$ intersects this plane then we need to find $t$ where $(R(t) - p_0) \cdot N = 0$ for some $t \geq 0$. So

Before plugging this $t$ back, we need to check that $t \in [1, t_{far}]$. If it’s not, then we just ignore this intersection. Now now take this $t$ value and plug it back into the ray equation to get the actual intersection point. This intersection is also ignored if we can find another intersection with a lower $t$ value.

Now we can drop the coordinate with the largest component in $N$ and then apply the scanline rendering test to test if a point is inside a triangle. We’ve discussed multiple ways to do this in the previous post.

Option 2: 3D Point Insdie a 3D Triangle

Instead of dropping a coordinate (projecting), we want to directly test if a 3D point is inside a 3D triangle. Given the $t$ value that we computed and after plugging it in $R(t_int) = R_0$, we get this intersection point $R_0$.

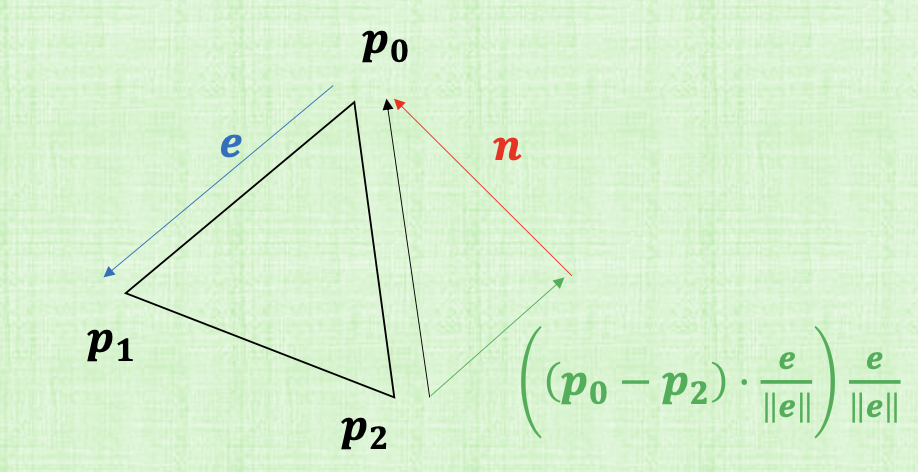

Take an edge from the triangle. Let $e =p_1 - p_0$. We compute its normal using,

$R_0$ is interior to $e$ when $(R_0 - p_0) \cdot n < 0$. We can compute the normal for the other two edges and then test if $R_0$ is interior to all three edges to determine if it’s inside the triangle. So pretty much the same as the 2D. Computing the normal is different.

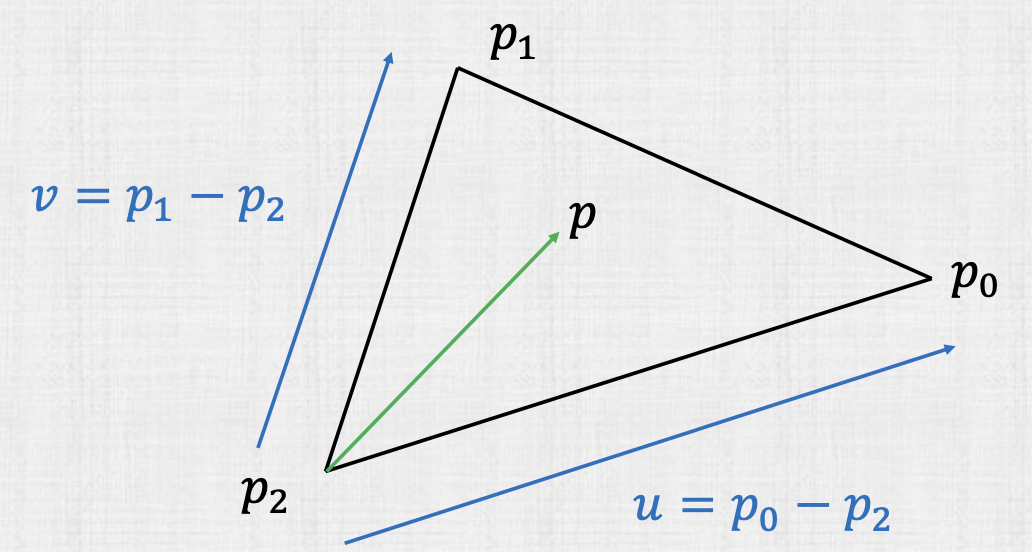

Option 3: Direct Ray-Triangle Intersection

Instead of doing the ray-plane intersection first, we can directly test if a ray intersects a triangle. We can compute the edge vectors

Any point $p$ interior to the triangle can be written as,

with $\beta_1, \beta_2 \in [0,1]$ and $\beta_1 + \beta_2 \leq 1$. Implying also that $\alpha_0 = \beta_1, \alpha_1 = \beta_2, \alpha_2 = (1 - \beta_1 - \beta_2)$

Recall that the ray is $R(t) = A + (P - A)t$ where $A$ is the aperture and $P$ is the pixel location. So now if we want to know for which $t$ we’re going to intersect this triangle, we’ll do

We’ll factor out the unknowns in its own column vector below,

$\begin{bmatrix}u & v & A - P\end{bmatrix}$ is a 3x3 matrix and $A-p_2$ is a 3x1 vector. Three equations and three unknowns. This system will have a unique solution unless:

- The triangle has zero area. (and so we ignore this point, no intersection).

- The ray direction $P - A$ is prependicular to the plane’s normal. This means it’s in the same direction as of the triangle edges so it doesn’t really hit it (even if it’s on it exactly, we’ll just skip it)

In these cases, we will ignore this intersection.

So as long as the ray has a tiny tilt, the matrix will be invertible and we can get a solution. This unique solution is inside the triangle if $\beta_1, \beta_2 \in [0,1]$ and $\beta_1 + \beta_2 \leq 1$. Morever, this intersection will be ingnored if we find another intersection with a lower $t$ value.

Cramer's Rule

We can solve the system of linear equations by using Cramer’s rule.

- Find the determinant of the matrix $\Delta = det(\begin{bmatrix}u & v & A - P\end{bmatrix})$. If it’s non-zero, then we have a solution.

- Compute $t = \Delta_t / \Delta$ where the numerator is $\triangle_t = \begin{bmatrix}u v A-p_0\end{bmatrix}$. If $t$ is outside $[1,t_{far}]$ we can just ignore this intersection (or if there is an earlier one).

- Compute $\beta_1 = \Delta_{\beta_1}/\Delta$ where $\Delta_{\beta_1} = det(\begin{bmatrix}A-p_0 v A-P\end{bmatrix})$. if $\beta_1 \notin [0,1]$, this isn’t a valid intersection for us.

- Compute $\beta_2 = \Delta_{\beta_2}/\Delta$ where $\Delta_{\beta_2} = \begin{bmatrix}u A-p_0 A-P\end{bmatrix}$ if $\beta_2 \notin [0,1]$, quit.

Ray-Object Intersections

We can apply the same technique to see if our ray hits any object. We don’t need this geometry to be turned into triangles like in the scanline rendering method. The general process is to try and write a function for the geometry. For example an implicit surface function. In this case, we know a point $p$ hits the surface if $f(p) = 0$. so now we just solve for $t$ in $f(R(t)) = 0$. We’ll study the ray-sphere intersection next.

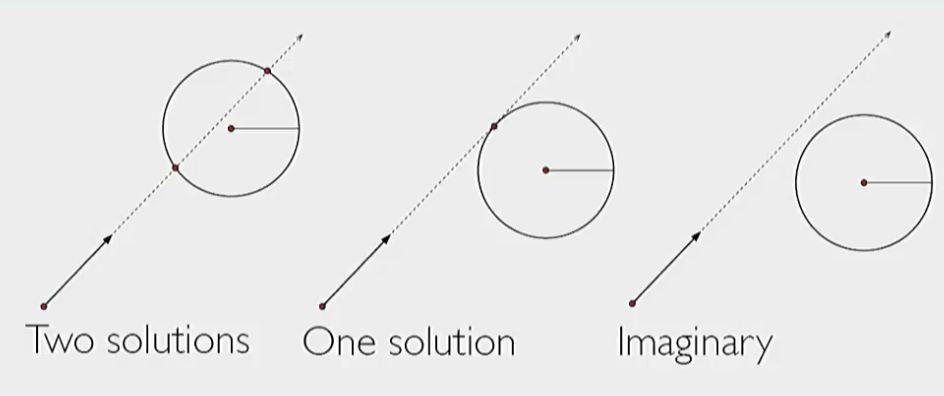

Ray-Sphere Intersection

A point is on a sphere with radius $r$ and center $C$ if $\left\lVert p-C \right\rVert_2 = r$. So now we substitute the ray equation $R(t) = A + (P - A)t$ in for $p$ and solve it.

- if the square root is positive then we have solutions, we’ll choose the first one that hits the ray.

- If zero, there is one solution at the tangent.

- If negative, no solutions.

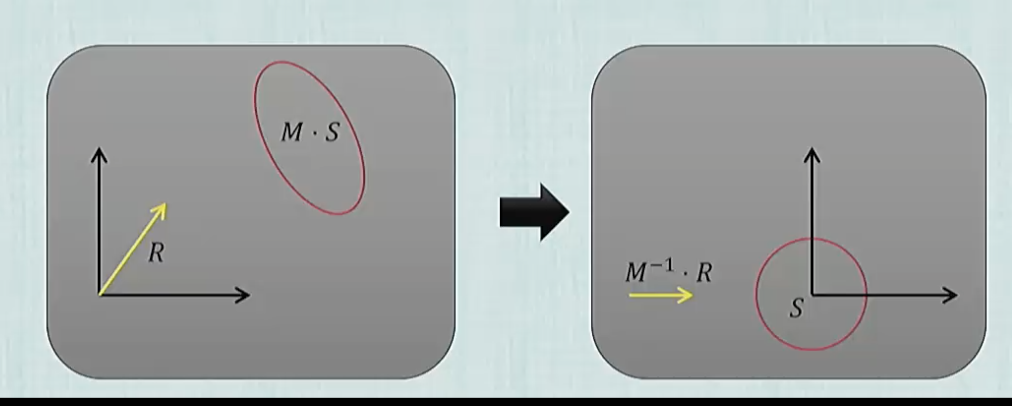

Transformed Objects

One optimization that is done to make testing faster to take the ray back to object space and perform the hit testing there. We know the geomtry is in object space (doesn’t leave the amazon box) and we know that we’re only applying this one matrix transform $M$ to place it in world space. The idea is to take the ray back to object space by applying the inverse of the transform on the ray so

and now the object say a chair that’re testing if we hit and the ray itself are both in object space. Once we find the intersection point $R(t_int)$ and before we use it, we need to apply $M$ again to bring it back to world space so

Code Acceleration: Bounding boxes

… TODO … kd-trees, octrees, etc

Normals

Objects titled towards the light are bombarded with more photos than those titled away from the light. In order to know which parts of the objects will be dimmer or brighter, we have to know how the surface of this object is aligned with the light source. How do we do this? Using Normals.

-

We already know the point of intersection that we computed $R(t_{\text{int}})$. The surface normal at this point can be used to approximate a plane tangent to the surface. So in a ray tracer whenever we compute the point of intersection, we always have to compute the normal along with it at this point.

-

Next, take the unit incoming light direction $\hat{L}$ (The light direction is from the light source to the point of intersection at the object). Now, take the dot product.

This tells us how well the normal to the object surface is aligned to the light source:

- If they align really well and they’re in the same direction, then the product is 1.

- If they’re prependicular so the light is just missing the object, then the product is 0.

- This should be scaled down to $max(0, cos(\theta))$ to prune surfaces facing away from the light.

Let $(k_r,k_g,k_b)$ be the reflection coefficients which should tell us the amount of the light that should bounce off the triangle and go into the camera. For example, if we store (1,0,0) at all the vertices of the triangle. This just means that blue light will bounce off to the camera). Then we’ll calculate the pixel of the color using

where:

- I is the total amount of light hitting the triangle which we’ll assume it is some white light intesity for now.

- $max(0,cos(\theta))$ tells you much to scale it down with since it’s based on the tilting of the normal of the triangle.

- $(k_r,k_g,k_b)$ are the reflection coefficients.

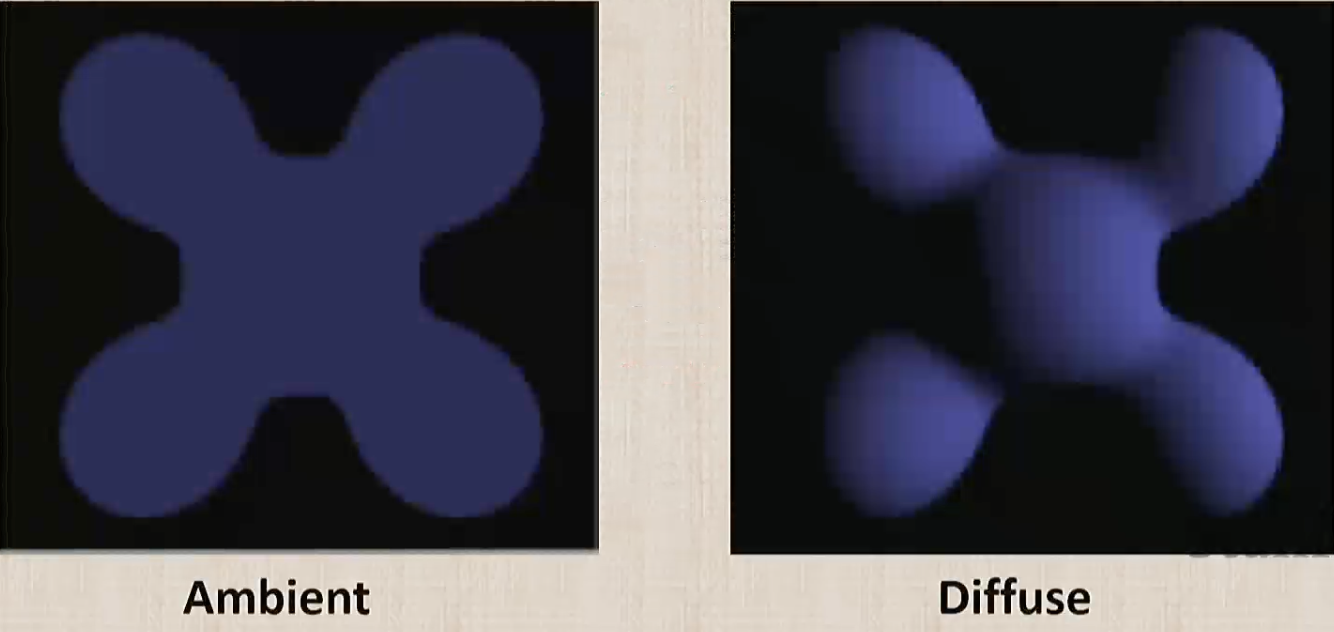

Ambient vs. Diffuse Shading

This figure summarizes what happens if we just use the $cos(\theta)$ above.

- Ambient: colors a pixel when its ray intersects the object.

- Diffuse Shading: takes into account how far the unit normal is titled away from the incoming light.

Computing Unit Normals

- The unit normal to a plane is used in the plane’s definition and is readily accessible.

- The unit normal to a triangle can be computed by normalizing the cross product of two edges. Be careful with the edges ordering to ensure that the normal points outwards from the object.

- For other objects, we need to provide a function that returns an outward unit normal for any point of intersection. For example, for a sphere that has intersection point $R_{\text{int}}$,

Normals in World Space vs. Object Space

If we decide to do the intersection test in object space rather than world space by transforming the ray to place it in the amazon box and find this intersection point along with the normal, then this normal needs to be transformed back into world space along with the point.

- Let $u$ and $v$ be edge vectors of a triangle in object space.

- let $Mu$ and Mv be the world space corresponding vectors.

- The object space normal $\hat{N}$ is transformed to world space with:

Note that $Mu \cdot \hat{N} = u^TM^TM^{-T}\hat{N} = u^T \hat{N} = 0$.

Also $M^{-T}\hat{N}$ needs to be normalized to make it unit length.

DO NOT use $M \hat{N}$ as the world space normal. It doesn’t work.

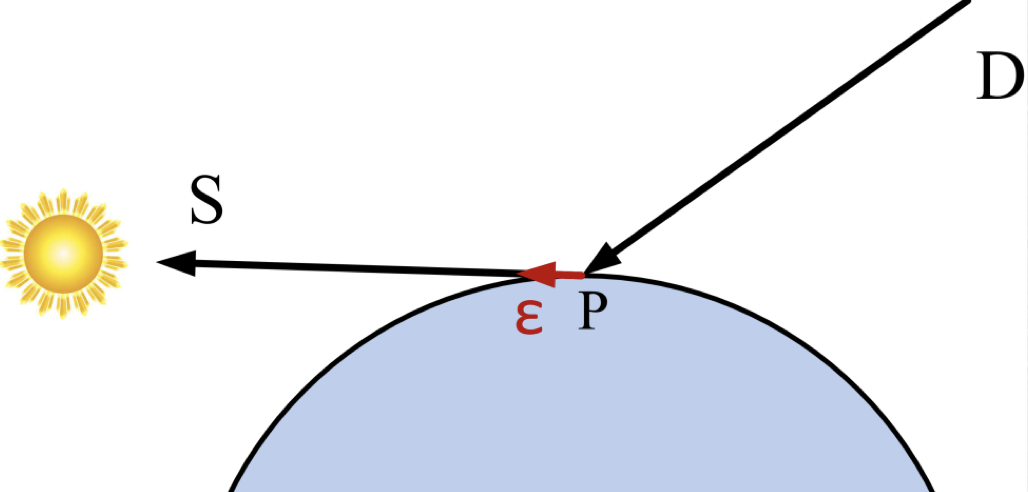

Shadows

We want to reduce the incoming light intesity $I$ when photons are blocked by other objects. Shadow rays determine whether photons from a light source are able to hit a point. A shadow ray then is cast from the intersection point $R_{\text{int}}$ in the direction of the light $-\hat{L}$ ($L$ from last time is the direction of light from the source of the light to the intersection point so $-L$ goes toward the light source). Therefore we will have:

with $t \in [0, t_{\text{light}}]$. Three things to note

- Not finding any intersections means that the light is not blocked by anything. Otherwise, the point is shadowed and the light source is not used to color the pixel.

- We will need a shadow ray for each light source in the scene.

- We will also use some low intensity ambient shading to color points that are completely shadows.

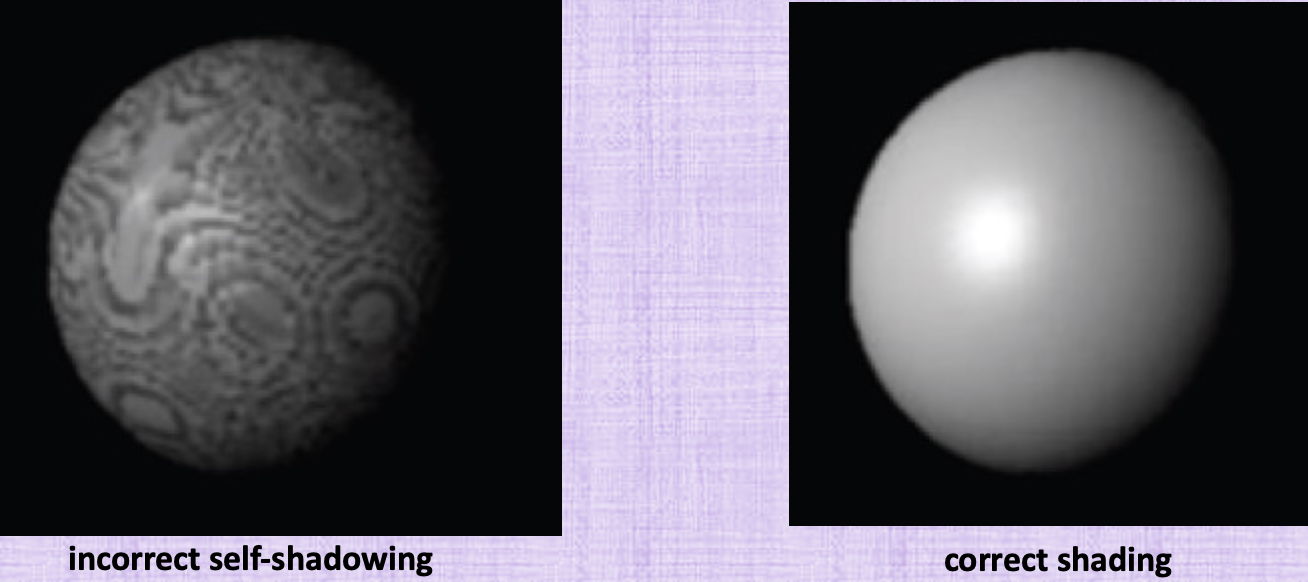

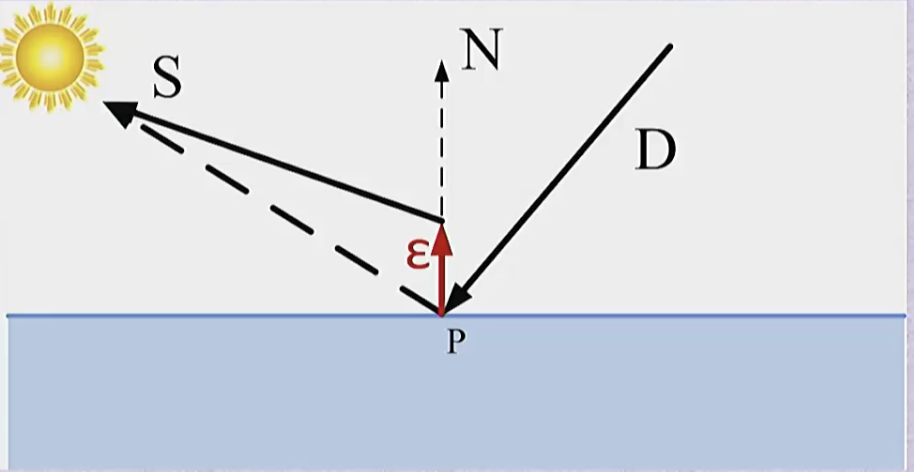

Spurious Self-Occlusion

So you cast shadow rays. Some will hit the light and get colored brighter. Some will actually hit the sphere itself (say a point toward the back in the picture) and in this case, they won’t be colored by this light source since they’re occluded and that’s fine. Sometimes though (left figure), you cast a shadow ray expecting to hit the light but instead, you find yourself hitting the object itself. Why? If you start $t=0$ and because of numerical precision errors and how close you are to the object, you might get a point that intersects the object so now you’re occluded. The solution is starting from some $\epsilon$ instead of 0 to guarantee that this is happen and this works most of the time except for when for example the shadow ray is flat so even with $\epsilon$, we’re still grazing the object seen below:

To fix this, we will perturb the starting point by moving a small amount in the normal direction to guarantee that we don’t intersect the object as seen below,

So the new shadow ray will be like

note here that the light direction is modified a little bit since we changed the start point.

References

Fundamentals of Computer Graphics, 4th Edition

CS148 Lectures