These are notes I took while watching the series The Essence of Linear Algebra by 3Blue1Brown.

Introduction

One of the main uses of linear algebra is that it lets us solve a linear system of equations. So if we’re given for example the following set of equations,

We can group all the coefficients in a matrix \(A\), all the variables in a vector \(\vec{x}\) and all the constants in a vector \(\vec{v}\). We can then write,

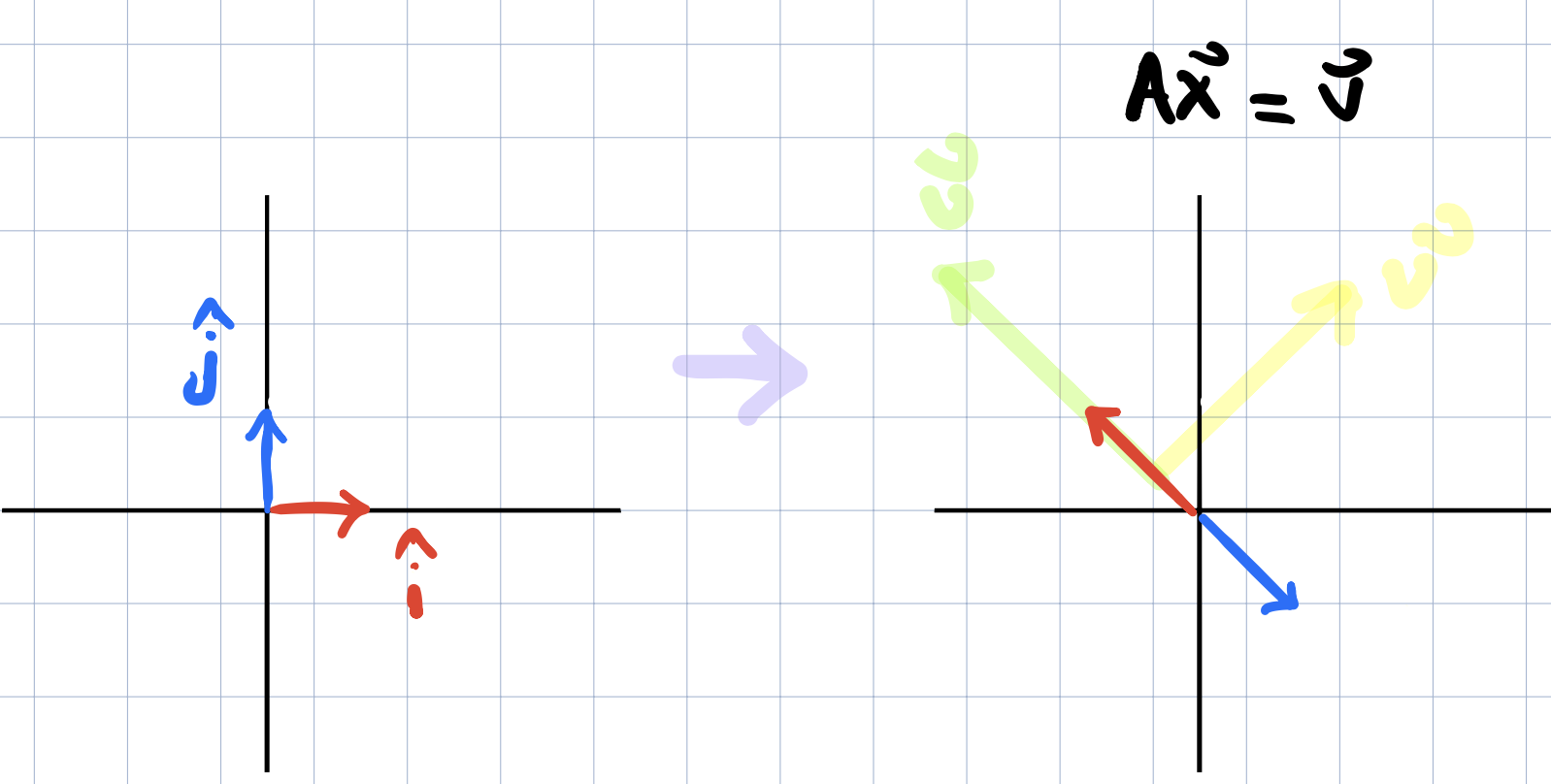

This should look very familiar! The matrix \(A\) corresponds to some linear transformation so solving \(Ax=v\) means we’re looking for a vector \(x\) which after applying the transformation \(A\), lands on the vector \(v\)!

A 2D Example

Let’s start with a simple example in two dimensions such that the matrix \(A\) is a 2x2 matrix. Suppose we have two equations and two unknowns. The equations are

and after re-arranging everything, we’ll have

The solution to this system depends on whether A squishes all of the space into a lower dimension or whether it leaves everything still in two dimensions where it started. One way to determine this to use what we learned in the last’s lecture and compute the determinant of this matrix.

- If it's zero, then we know, we're squished to a lower dimension.

- If it's non-zero, then we know we have a unique solution.

We’ll analyze each case separately next.

Case 1: The Determinant is not zero (The Inverse of a Transformation)

In case 1, the determinant is not zero. This means the area is not zero and we’re not squished to a lower dimension. Therefore there will be only one vector \(x\) such that \(Ax = v\). To find it, we really want to play the transformation in reverse going from \(v\) to \(x\) (imagine playing it slowly from \(\vec{v}\) back to \(\vec{x}\)). In other words, we want the inverse transformation applied to \(v\). The inverse of a transformation \(A\) is called the inverse of \(A\) and is denoted by \(A^{-1}\). \(A^{-1}\) is the unique transformation with the property that if you first apply \(A\) and then follow it with \(A^{-1}\), you end up back where you started. And we know that applying multiple transformations is captured algebraically with matrix multiplication. So \(AA^{-1}\) corresponds to the transformation that does nothing! The transformation that does nothing is called the identity transformation. It leaves both \(\widehat{i}\) and \(\widehat{j}\) unchanged so \(I = matrix (1,0,0,1)\).

So now to find the unique solution, we can just apply the inverse to both sides of the equation

Again it’s important to stress the geometric meaning of this equation. We’re playing the transformation \(A\) in reverse from \(v\) and following it back to \(x\).

Case 2: The Determinant is Zero

So we know when the determinant is zero, this means that the two dimensions are squished onto a lower dimension. So there is no inverse because we can’t unsquish a line to turn it into a plane. It is though still possible that a solution exist even when the determinant is zero. It’s just when the whole space is squished into a line, we have to lucky that the vector \(v\) lives somewhere on that line. (green means there is a solution and yellow indicates no solution exists)

Rank

If we take a 3x3 transformation in 3 dimensions where the determinant is zero, we will notice that some of these zero determinant cases feel a lot more restrictive than others. It seems that it will be harder to find a solution if we’re squished to a line versus for example getting squished to a plane. This leads us to develop new terminology to distinguish these cases. We’ll say the transformation that squishes us to a 1 dimensional line has rank 1. If we’re squished to 2 dimensions, then the tranformation has rank 2.

So really the rank is the number of dimensions in the output of a transformation. So in the 3x3 case, rank 3 is the best rank the matrix can reach and it means that the basis vectors continue to span the full three dimensions of space and the determinant is not zero!

Column Space

The set of all possible outputs of the 3x3 transformation is called the column space of \(A\) of the transformation whether it’s a line, a plane or 3D space.

Why did we call it the column space? We know that each column in the matrix \(A\) refers to where a vector from the basis vectors have landed. For example the first column is where \(\widehat{i}\) has landed, the second is where \(\widehat{j}\) has landed and so on. The span of those transformed basis vectors gives you all possible outputs. In other words, the column space is the span of the columns of your matrix.

Null Space

Another important thing is that the zero vector will always be included in the column space since linear transformations must keep the origin fixed in place. If the matrix is full rank, then the zero vector is the only vector that lands at the origin. But for other non full rank matrices, we can have a bunch of vectors land on zero. These vectors are called the null space or the kernel of your matrix. It’s the set of all vectors that become null (land on the zero vector).

If we’re trying to solve \(A\vec{x}=\vec{0}\), then the null space gives you all of the possible solutions to the equation.