These are notes I took while watching the series The Essence of Linear Algebra by 3Blue1Brown.

The Determinant

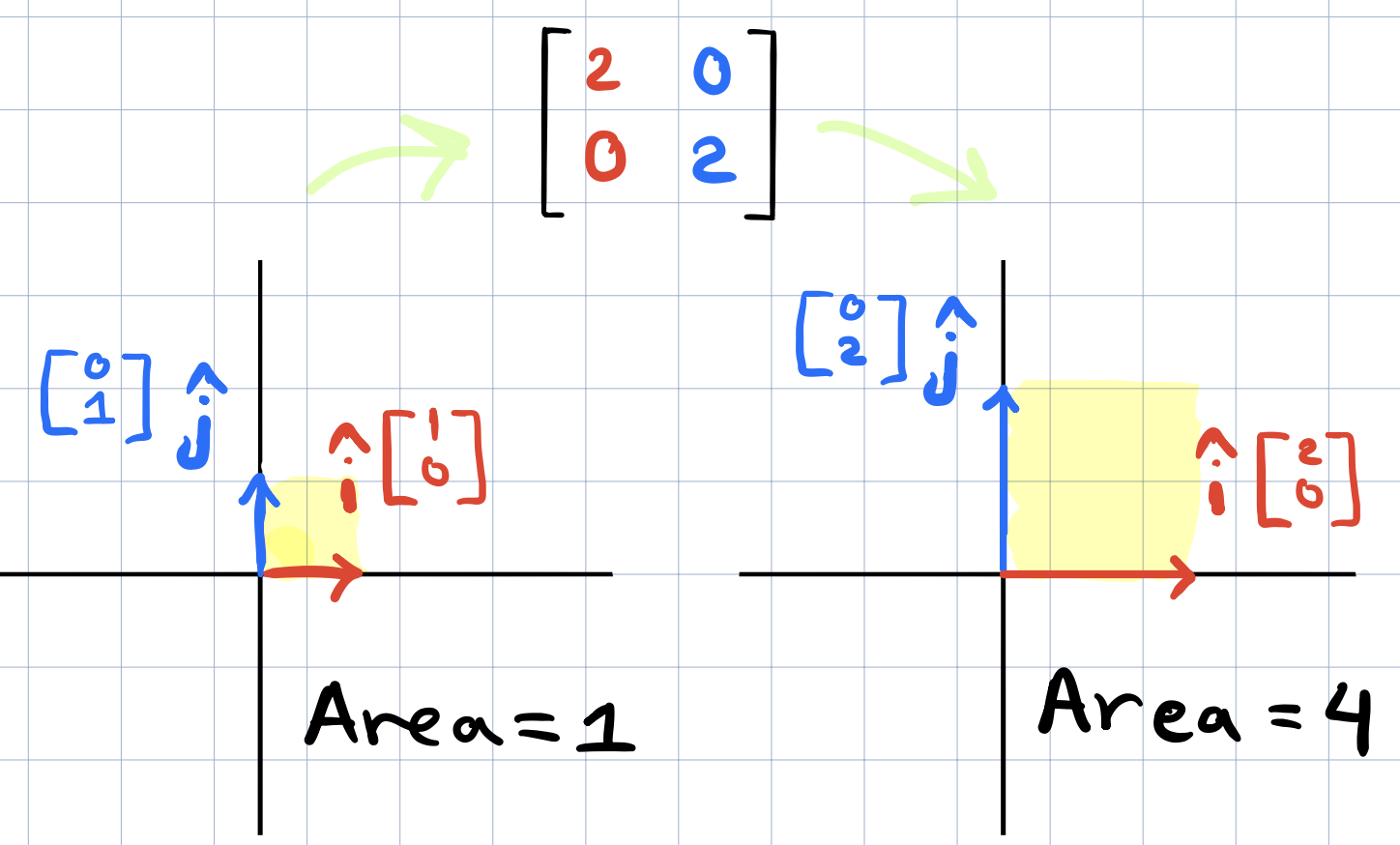

We’ve talked about linear transformations previously. Some squish the space and some stretch the space (while of course keeping the grid lines parallel and evenly spaced and the origin in the same place). How can we measure the amount of stretching? Given an area bounded by some region, how much will its area grow by after applying some transformation? For example in the below figure, we can see that the shaded area on the left has area \(A = 1\). After the transformation was applied, this area grew by a factor of 4 so the new area is now \(4*A\). So the transformation scaled the area by a factor of 4.

The important fact here is that knowing how much the area of that one single unit square changes is enough to know how much any area will change in the space! This follows from the fact that the parallel grid lines remain parallel and evenly spaced. This scaling factor by which a linear transformation changes any area is called the determinant

More Examples

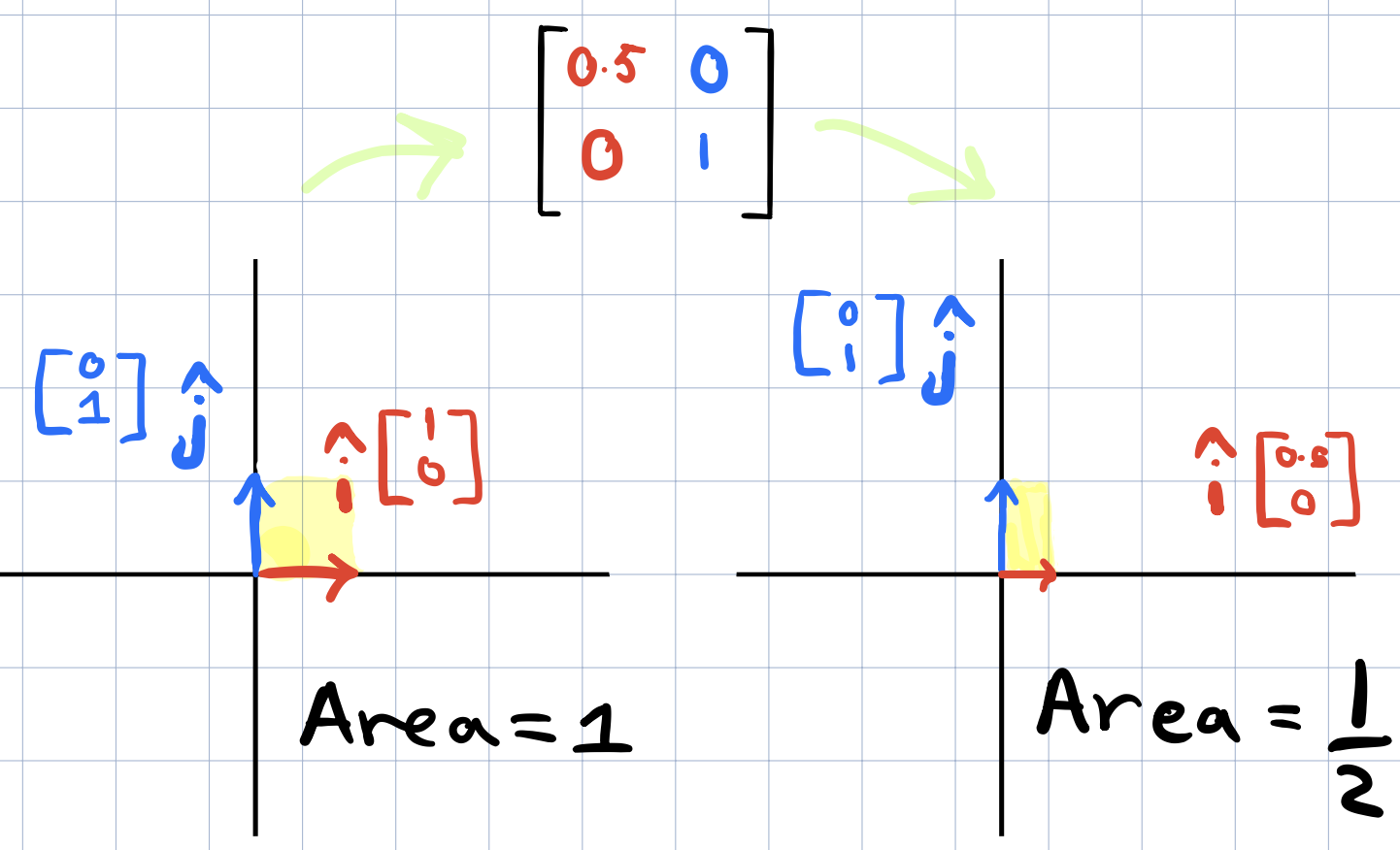

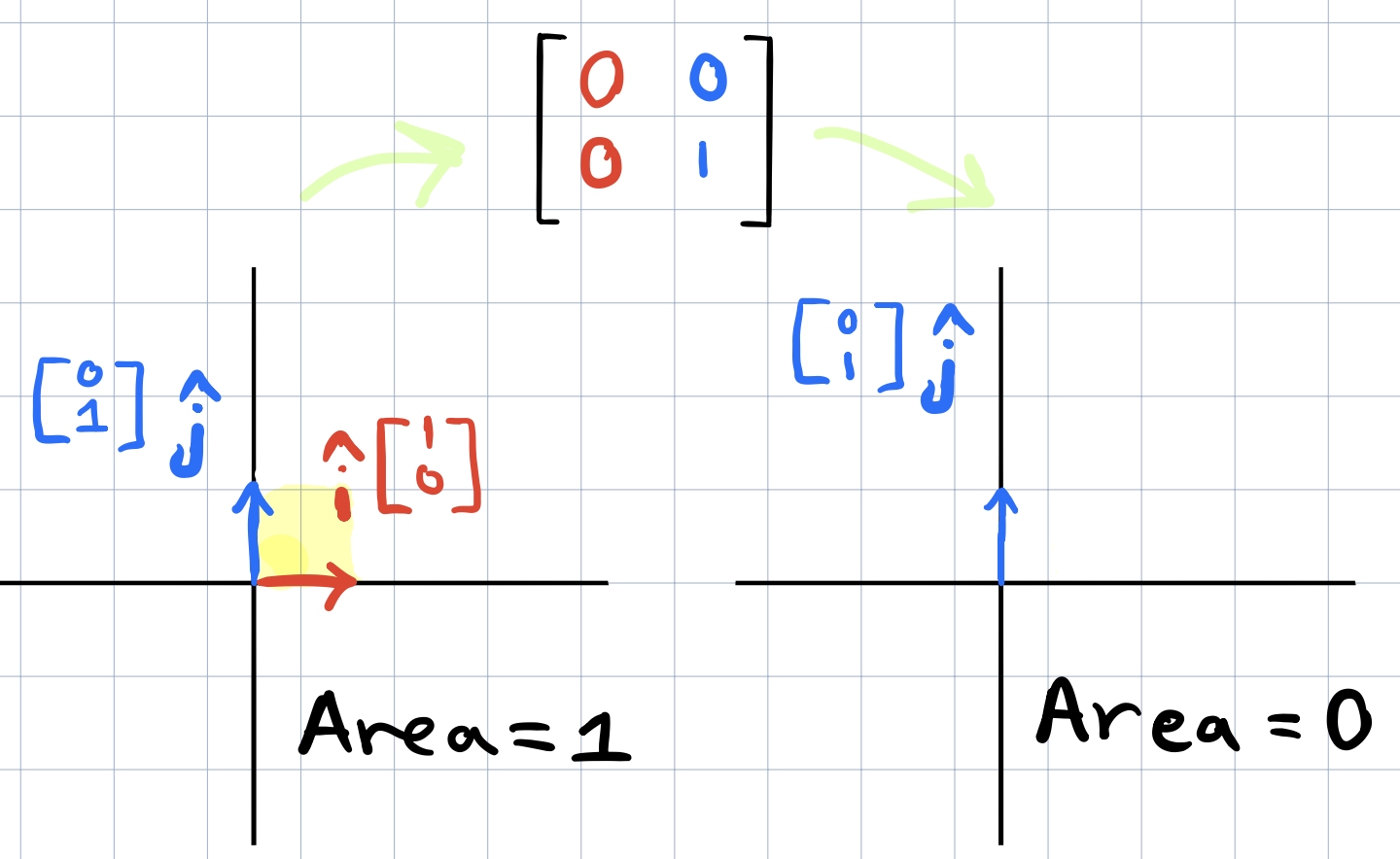

To re-iterate, the determinant is the scaling factor by which a linear transformation changes any area. And it applies to any area because a linear transformation keeps the parallel lines parallel and evenly spaced. Let’s look at some example:

Here, we know that the determinant of that transformation (aka, the factor by which any area would scale) is 0.5. Let the area be \(A\) before the transformation. The new area after the transformation will be \(0.5*A\) So the determinant is 0.5.

This is another example where the area is completely squished and it’s just zero. This means that the area of any region would become also 0 after applying this specific transformation. This is really important because it means that checking if the determinant of a given matrix is 0, will give away wether or not the transformation associated with that matrix squishes everything into a smaller dimension.

Negative Areas?

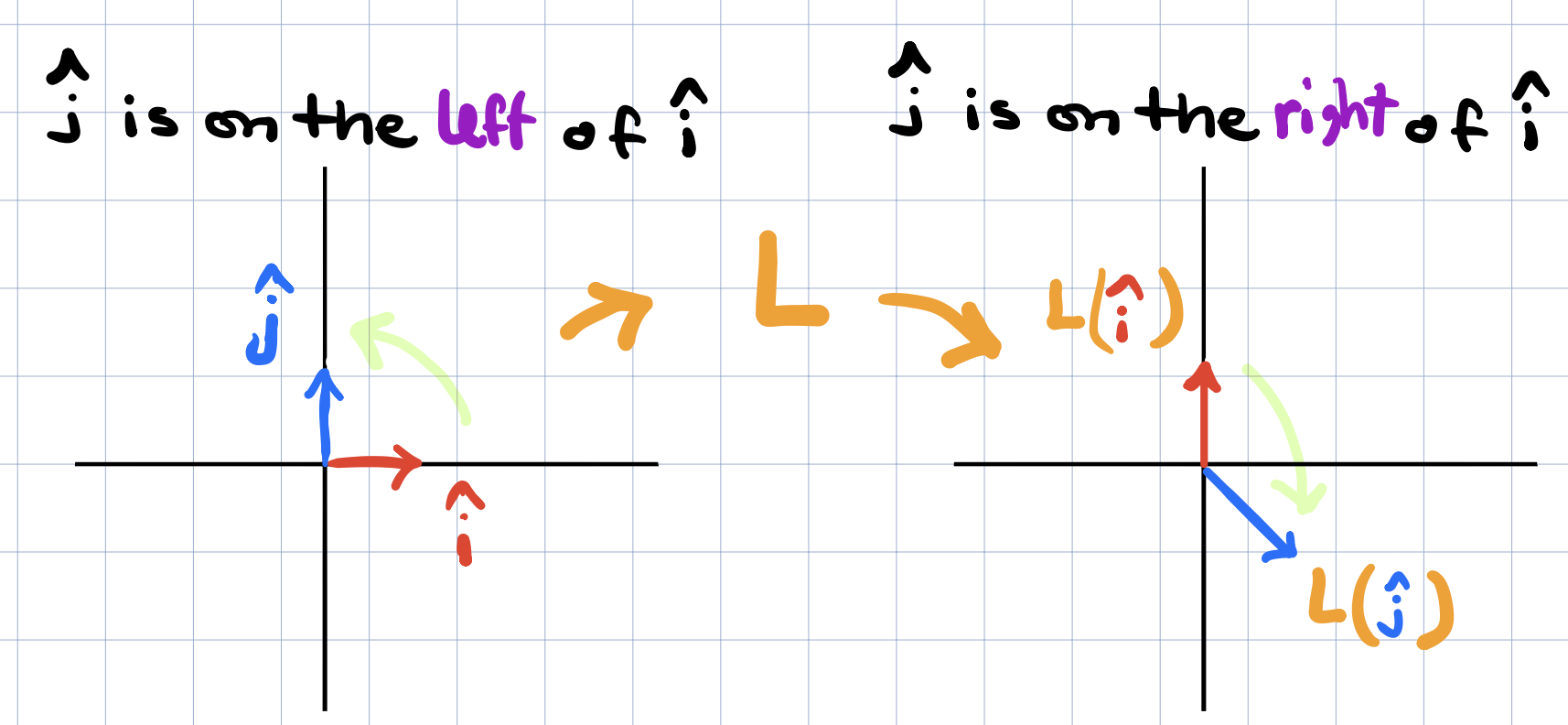

Unfortunately, the determinat can be negative! so what would scaling an area by a negative amount even mean? This has to do with the concept of orientation. One way to think about this is to notice that some transformations flip the space (like flipping a sheet of paper). Transformation that flip the space are said to “invert the orientation of space”. (video has beautiful animations for this!)

Another way to think about this is in terms of \(\widehat{i}\) and \(\widehat{j}\). Notice that in the above figure and before applying the tranformation, \(\widehat{j}\) is to the left of \(\widehat{i}\). After applying \(L\), \(\widehat{j}\) is now on the right of \(\widehat{i}\). Whenever the orientation of the space is inverted, the determinant will be negative. But regardless of the sign of the determinant, the absolute value will still determine the scaling factor by which the area of any region will change!

Three Dimensions

What about the determinat of a linear transformation in 3 dimensions! This time it will tell us how much the volume of a region will get scaled by! Instead of focusing on the single 1x1 square in dimensions, now we can focus on the 1x1x1 cube and observe what happens to it after the transformation.

What about negative determinants? What does orientation mean here? We will follow the right hand rule to determine the orientation. Point the forefinger of your right hand in the direction of \(\widehat{i}\), your middle finger in the direction of \(\widehat{j}\) and your thumb in the direction of \(\widehat{k}\). If your thumb stays in the same direction after the transformation, then the orientation hasn’t changed and the determinant will be positive. If instead, you can only do that with your left hand, then the orientation is flipped and the determinant is negative.

Computing the Determinant

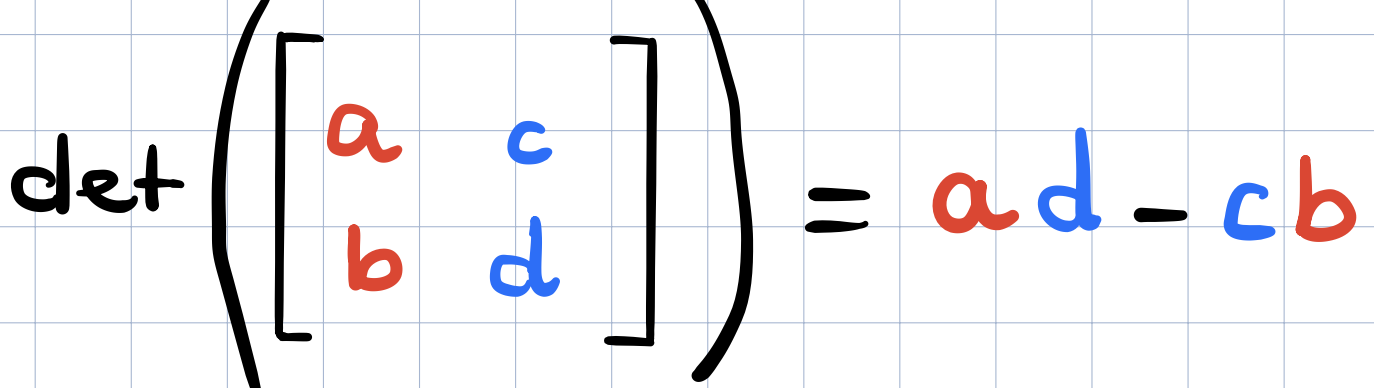

We compute the determinant numerically using the following

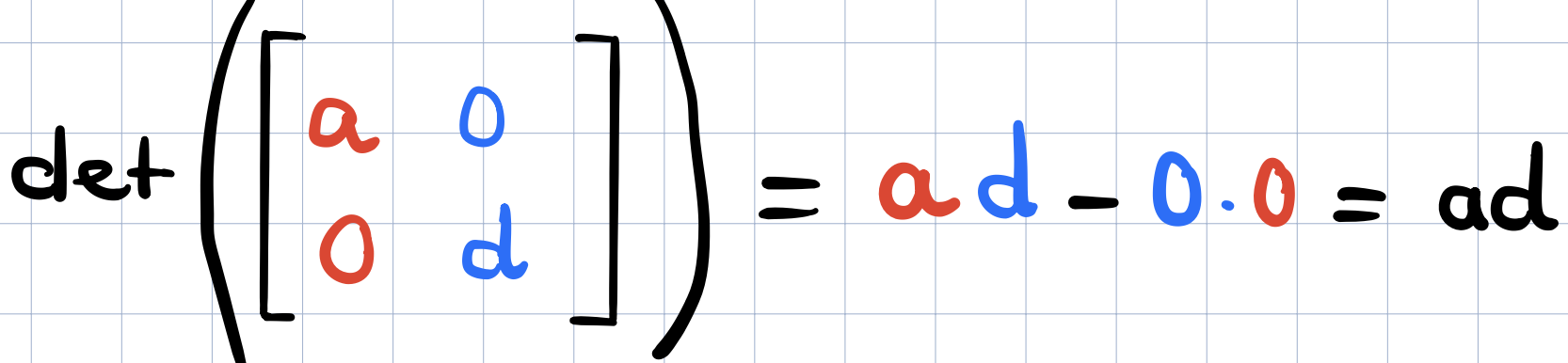

What’s the intuition behind this? Suppose that the terms \(c\) and \(d\) are zero and so in the above, the determinant will just the product \(ad\), shown below

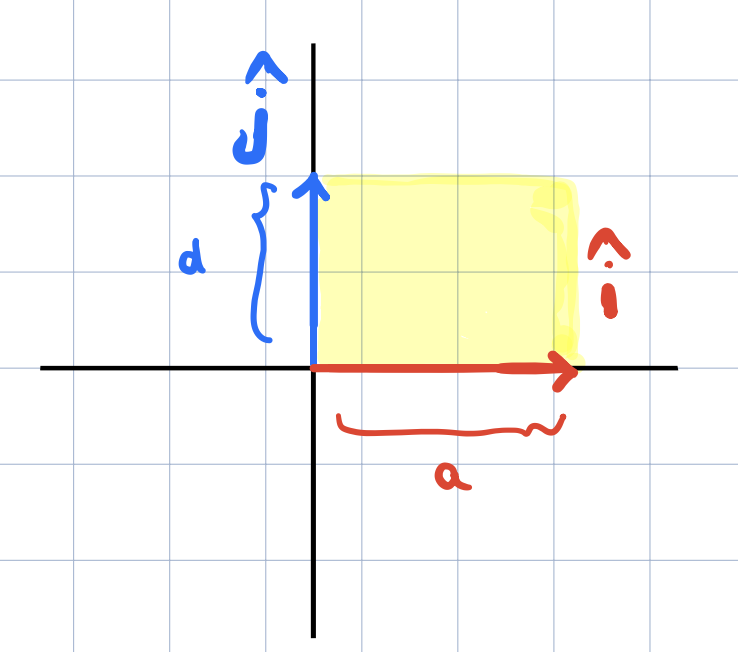

In this case \(a\) will tell us how much \(\widehat{i}\) is stretched in the \(x\) direction and the term \(d\) will tell us how much \(\widehat{j}\) is stretched in the \(y\) direction show below,

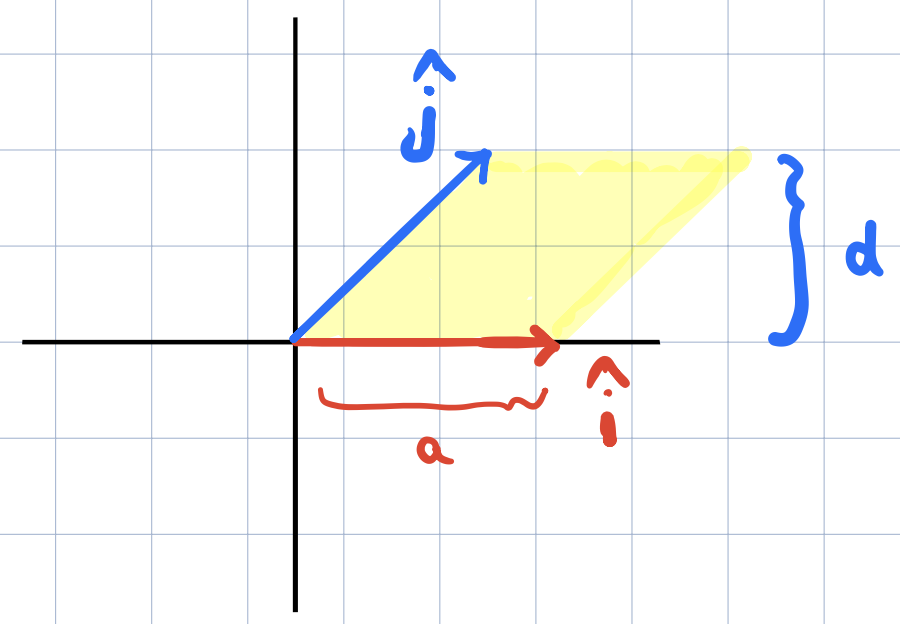

This should make sense since now \(a*d\) is also the area of the rectangle of what the unit square has turned into. What if only \(b\) or \(c\) are zero and not both! Numerically, the determinant is still \(ad\) and so it doesn’t change but visually it’s the area of the parallelogram with base \(a\) and height \(d\) as show below,

What if none of the terms are zero? there is a crazy diagram in the video that shows where the term is derived from exactly. Each piece of the area will be mapped to one of the terms in the crazy equation.