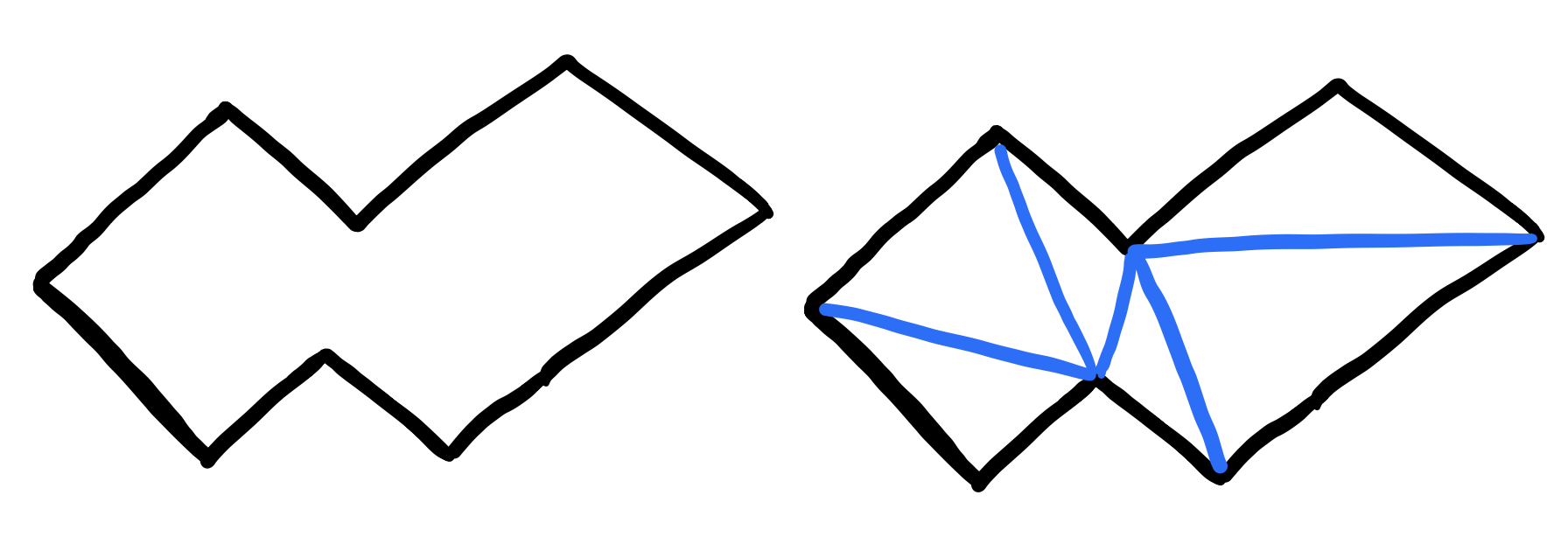

Given a simple polygon of \(n\) vertices, we define triangulation of \(p\) as the process of partitioning \(p\) into triangles whose vertices are the verties of \(p\). The claim is that every polygon can be triangulated and the key to proving that triangulation exists is proving the existence of a diagonal.

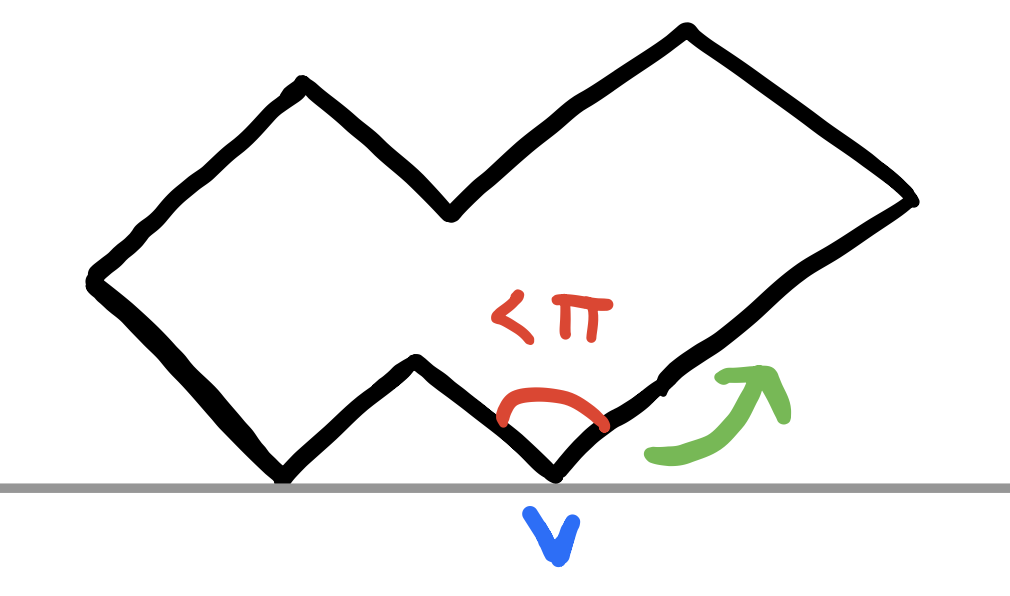

Every polygon must have at least one strictly convex vertex

A strictly convex vertex has an internal angle that is less than \(\pi\). The claim is that every polygon must have at least one strictly convex vertex.

Proof:

Let \(p\) be a simple polygon and let \(v\) be the the vertex with the lowest y-coordinate. if there are multiple, let \(v\) be the right most one. Let \(L\) be the line that goes through \(v\) (parallel to the x-axis?). We also know that the interior of \(P\) is above \(v\). If we were to traverse the boundary of \(p\) then when the walker is at \(v\), the previous stated conditions imply that the walker must take a left turn at \(v\) and so \(v\) must be a strictly convex vertex.

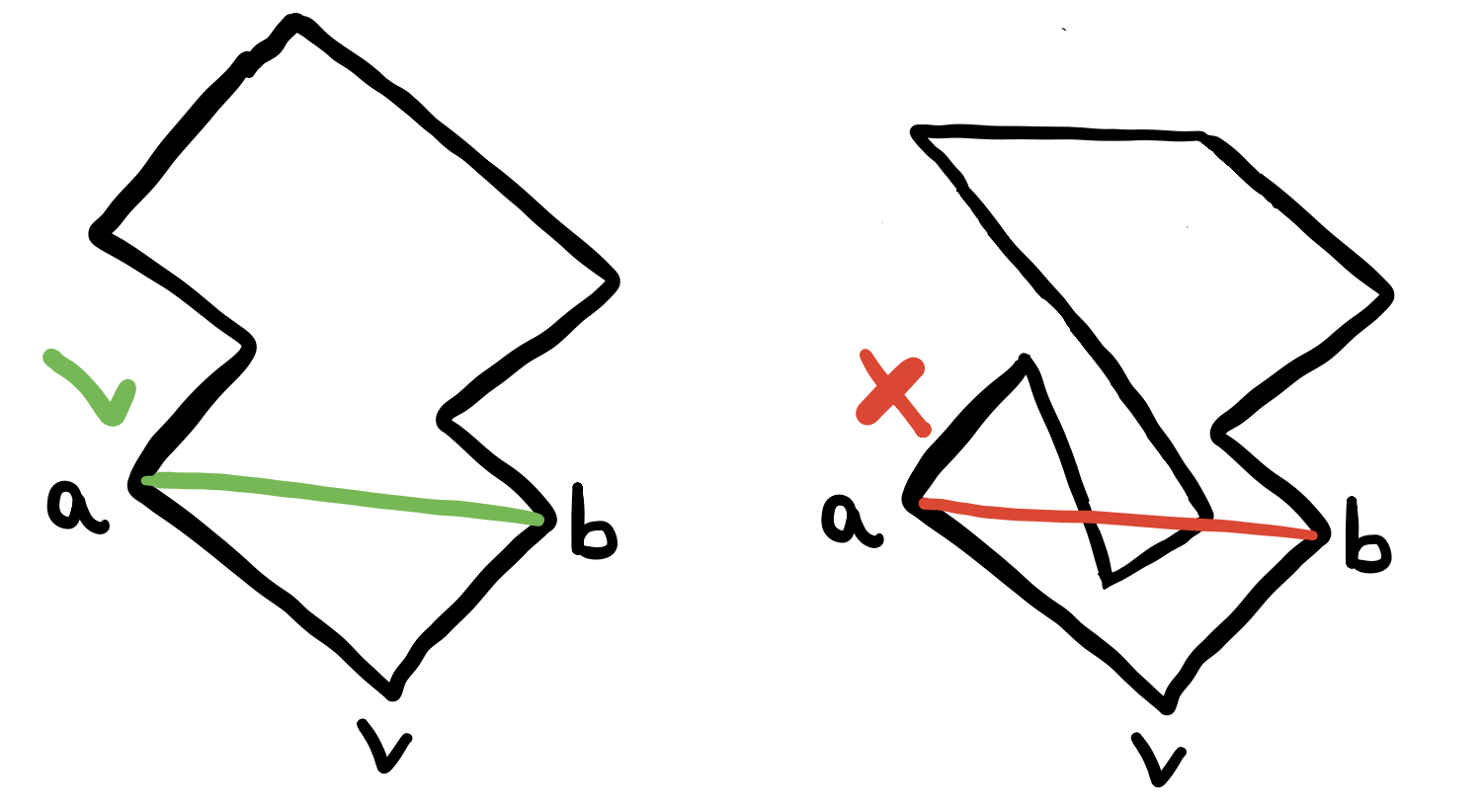

Lemma (Existence of a Diagonal): Every polygon of \(n \geq 4\) vertices has an internal diagonal

First recall from the Art Gallery post that a Diagonal is a line segment between two of the polygon’s vertices \(a\) and \(b\) such that the intersection of the line segment \(ab\) with the boundary of the polygon (\(\partial P\)) is exactly the set \(\{a,b\}\). We will prove that every polygon with more than 4 vertices must have an internal diagonal.

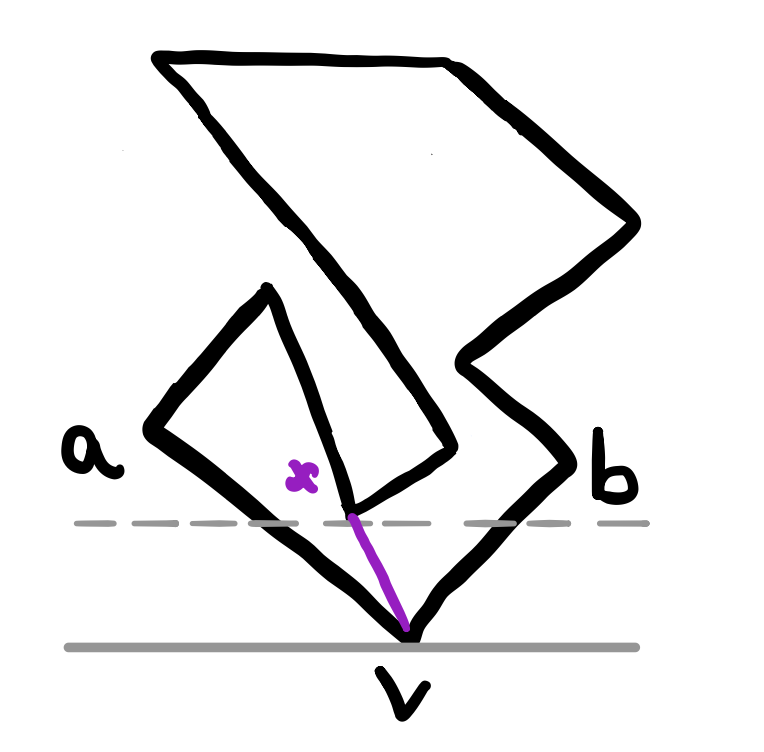

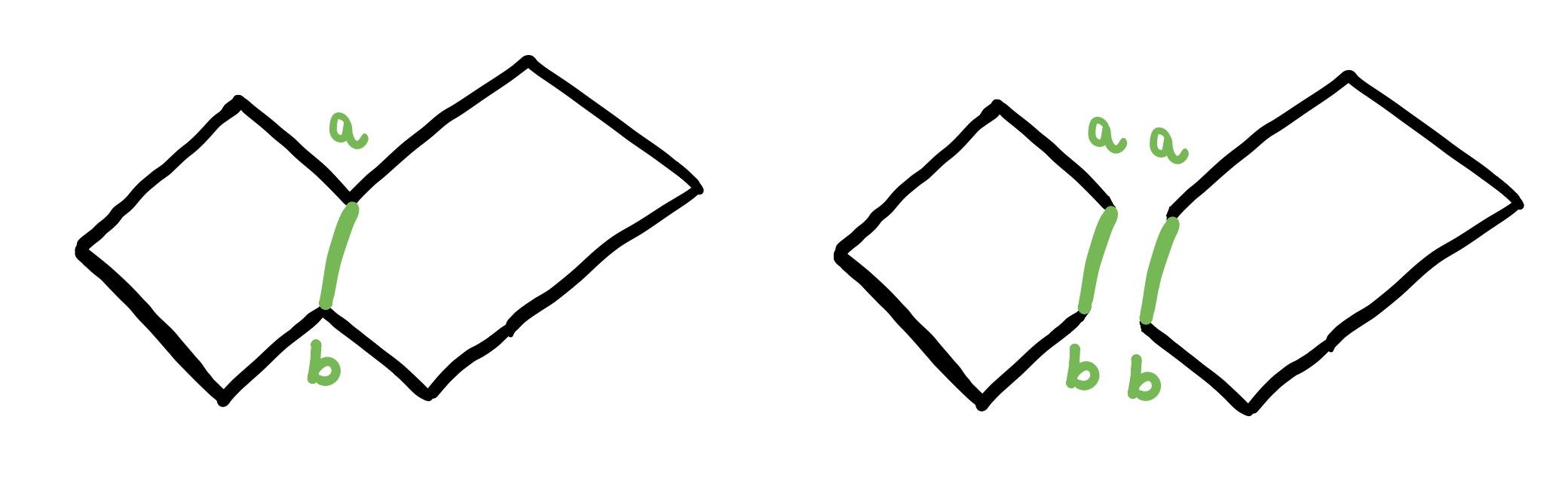

Proof: Suppose \(p\) is a simple polygon. We showed previously that \(p\) must have a strictly convex vertex. Let that vertex \(v\). Let \(a\) and \(b\) be the vertices adjacent to \(v\). There are two cases. If \(ab\) is a diagonal, then we’re done (left figure). If \(ab\) was not a diagonal, then either \(ab\) is exterior to \(p\) or \(ab\) intersects the boundary of \(p\) (right figure).

In either case, since \(n > 3\), then the closed triangle \(avb\) contains at least one vertex of \(p\) other than \(a\), \(b\) or \(v\). Draw a line parallel to \(ab\) that goes through the vertex \(v\) (It must be parallel, todo: add a picture for why it has to be). Then sweep upward from the line through \(v\) until you meet the first vertex that is not \(a\) or \(b\). Let this vertex be \(x\). Then \(xv\) must be a diagonal of \(p\). (TODO: MORE?)

Theorem (Triangulation): Every polygon \(P\) of \(n\) vertices maybe partitioned into triangles by the addition of (zero or more) diagonals

Proof:

Let \(p\) be a simple polygon with \(n\) vertices. We will prove that \(p\) can be partitioned into triangles by the addition of zero or more diagonals by induction on the number of vertices of \(p\).

Base case: \(n=3\), the polygon is a triangle and the theorem holds trivially (\(p\) is a triangle!).

Inductive Step: Let \(n>4\) and suppose the theorem is true for any polygon with fewer than \(n\) vertices. By the previous lemma, we know that \(p\) must have a diagonal. Let that diagonal be \(d\) and let its end points be \(a\) and \(b\). We know \(d\) only intersects the boundary of \(p\) and so \(a\) and \(b\) are vertices of \(p\). This implies that \(d\) partitions \(p\) into two polygons \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) with \(d\) as edge and \(a\) and \(b\) vertices in both. We know that both \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) must have fewer vertices than \(p\) since we’re not adding any new vertices in this process. It is also clear that there is at least one vertex in each part in addition to \(a\) and \(b\) (by the defintion of diagonal). We can now apply the induction hypothesis to \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) to complete the proof.

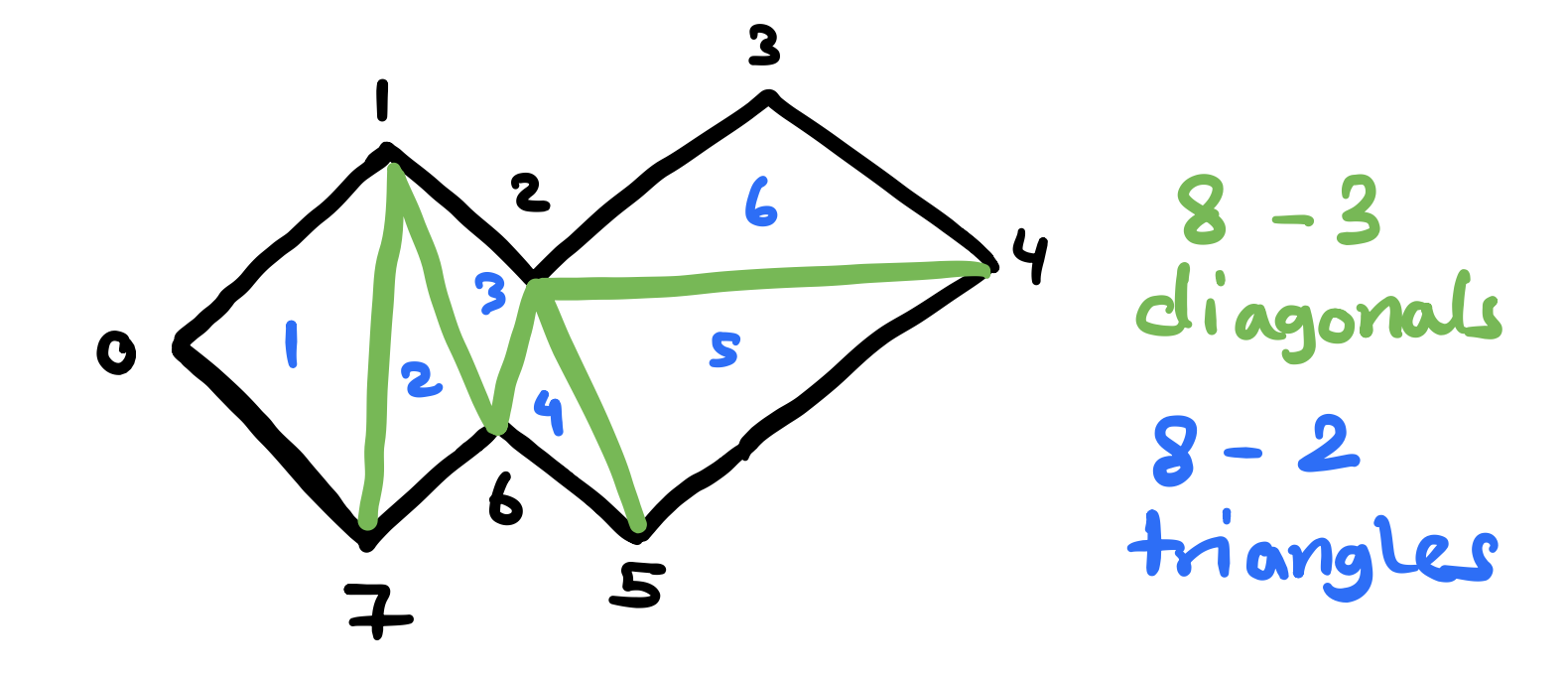

Lemma (Number of Diagonals): Every triangulation of a polygon \(p\) of \(n\) vertices uses \(n-3\) diagonals and consists of \(n-2\) triangles

Proof: Let \(p\) be a simple polygon with \(n\) vertices. We will prove that the triangulation of \(p\) uses \(n-3\) diagonals and consists of \(n-2\) triangles by induction.

Base case: \(n=3\), the polygon is a triangle and the theorem holds trivially. We have \(3-3=0\) diagonals and \(1\) triangle.

Inductive Step: Let \(n>4\) and suppose the theorem is true for any polygon with fewer than \(n\) vertices. Pick a diagonal arbitrary and let that diagonal be \(d\) where its end vertices are \(a\) and \(b\). This diagonal partitions \(p\) into two polygons. Let \(p_1\) and \(p_2\) be the two new polygons. Let \(p_1\) have \(n_1\) vertices and \(p_2\) have \(n_2\) vertices. We know that \(n_1 + n_2 = n + 2\). This is because \(a\) and \(b\) are counted twice in each polygon. By induction, \(p_1\)’s triangulation uses \(n_1-3\) diagonals and consists of \(n_1-2\) triangles and similarly \(p_2\)’s triangulation uses \(n_2-3\) diagonals and consists \(n_2-2\) triangles. Therefore, \(p\) will have \(n_1 - 3 + n_2 - 3 + 1 = n + 2 - 6 + 1 = n - 3\) diagonals and \(n_1 - 2 + n_2 - 2 = n + 2 - 4 = n - 2\) triangles.

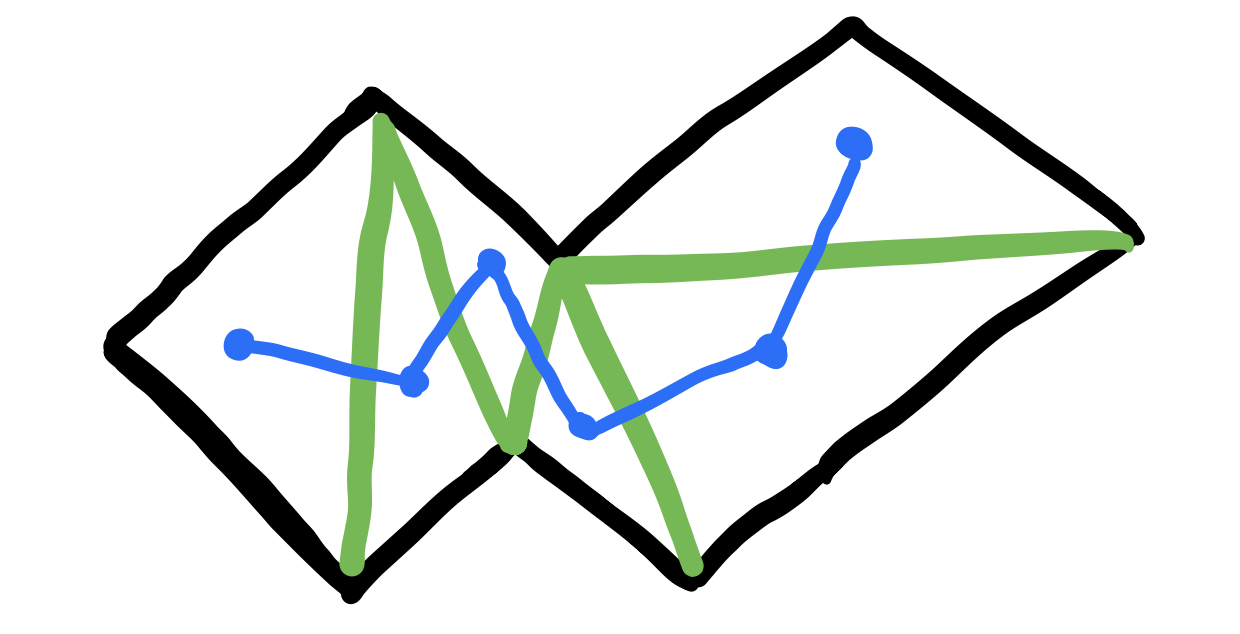

Triangulation's Dual

The dual of a triangulation of a polygon is a tree such that each node is associated with each triangle and an edge exists between a pair of nodes if and only if they share a diagonal. The book then states the following lemma: “The dual \(T\) of a triangulation is a tree with each node of degree at most three” (TODO: Proof).

Meisters's Two Ears Theorem: Every polygon of $$n \geq 4$$ vertices has at least two non-overlapping ears

A leaf node in the triangulation dual corresponds to a an ear. A tree of two or more nodes has \(n - 2\) nodes (each node corresponds to a triangle). We also know that a tree with two or more nodes must have two leaves.