Suppose we have an art gallery represented by a simple polygon \(P\) with \(n\) vertices. What is the minimum number of fixed guards needed to guard the gallery where each guard has a full visibility range of \(2\pi\). How do we know if a given point is in the range of visiblity of a given guard? We say that if we were given points \(x\) and \(y\), then \(x\) is visible from \(y\) if \(xy \in P\) where \(P\) is a given polygon and \(x, y \in P\). So if you connect the guard to a point with a line segment and all of that line segment is in \(P\), then the point is visible to the guard.

Simple Polygons

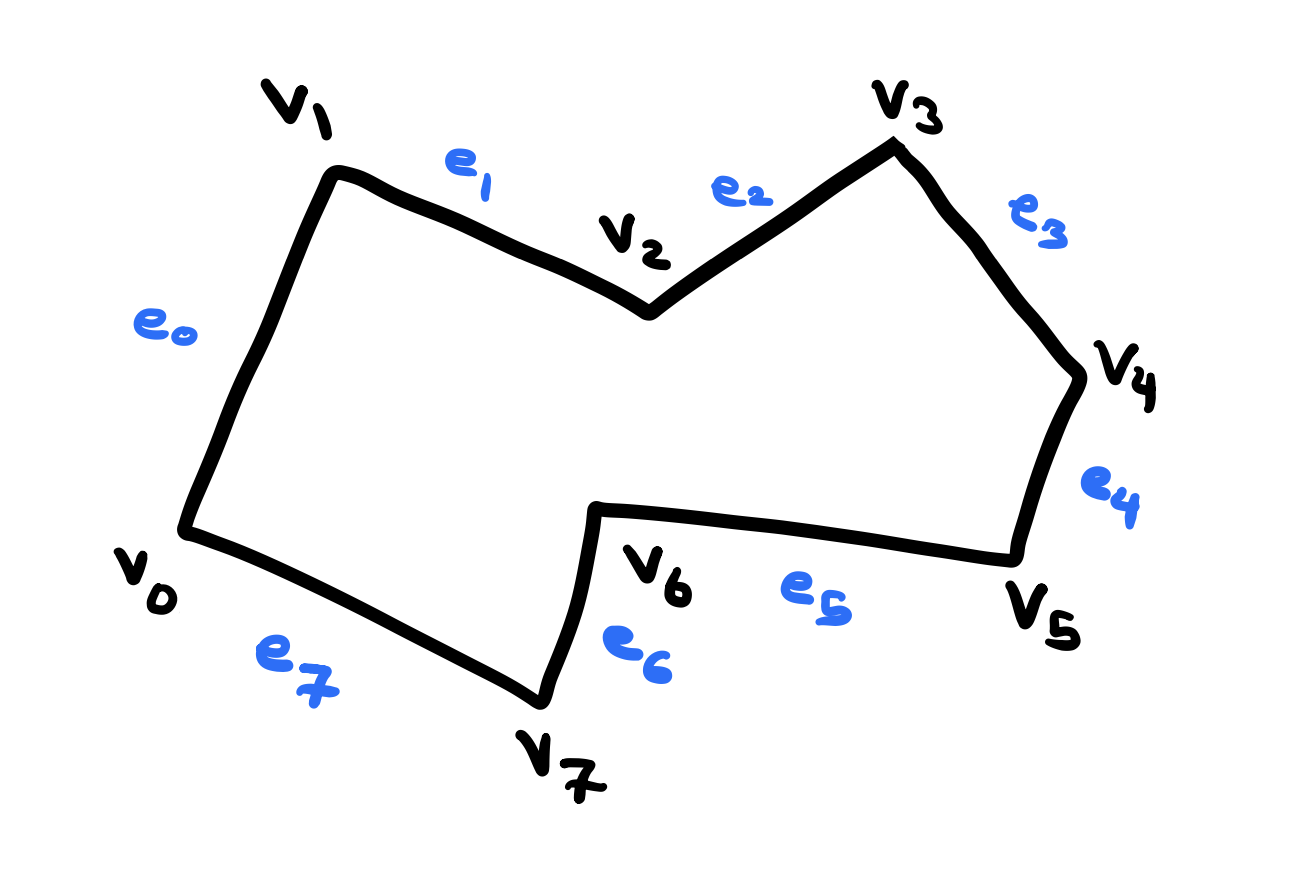

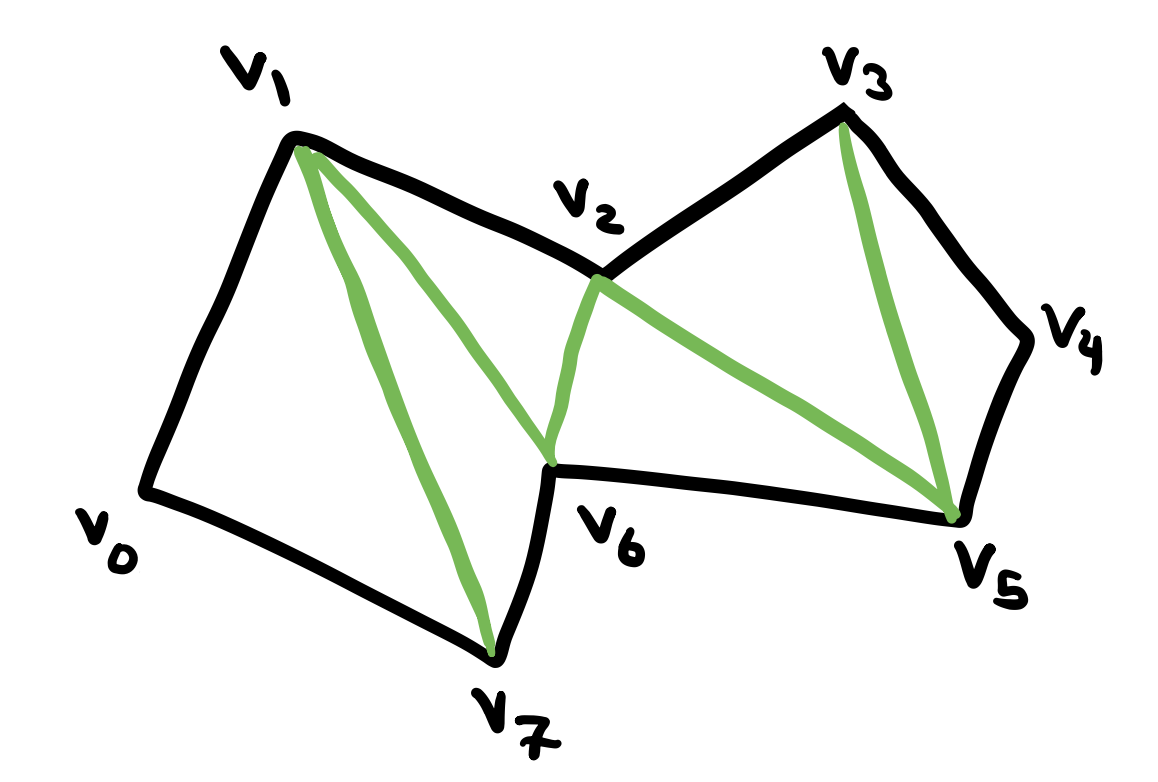

To start we first define a line segment as a closed subset of a line contained between points \(a\) and \(b\) called its end points. A simple polygon is a closed curve consisting of a finite collection of line segments that doesn’t intersect itself. This means that the intersection of each pair of adjacent segments is only the vertex shared between them and such that non-adjacent segments do not intersect. In the figure above, the intersection of \(e_i\) and \(e_{i+1}\) is only \(v_i\) and none of non-adjacent segments intersect.

Diagonals in Polygons

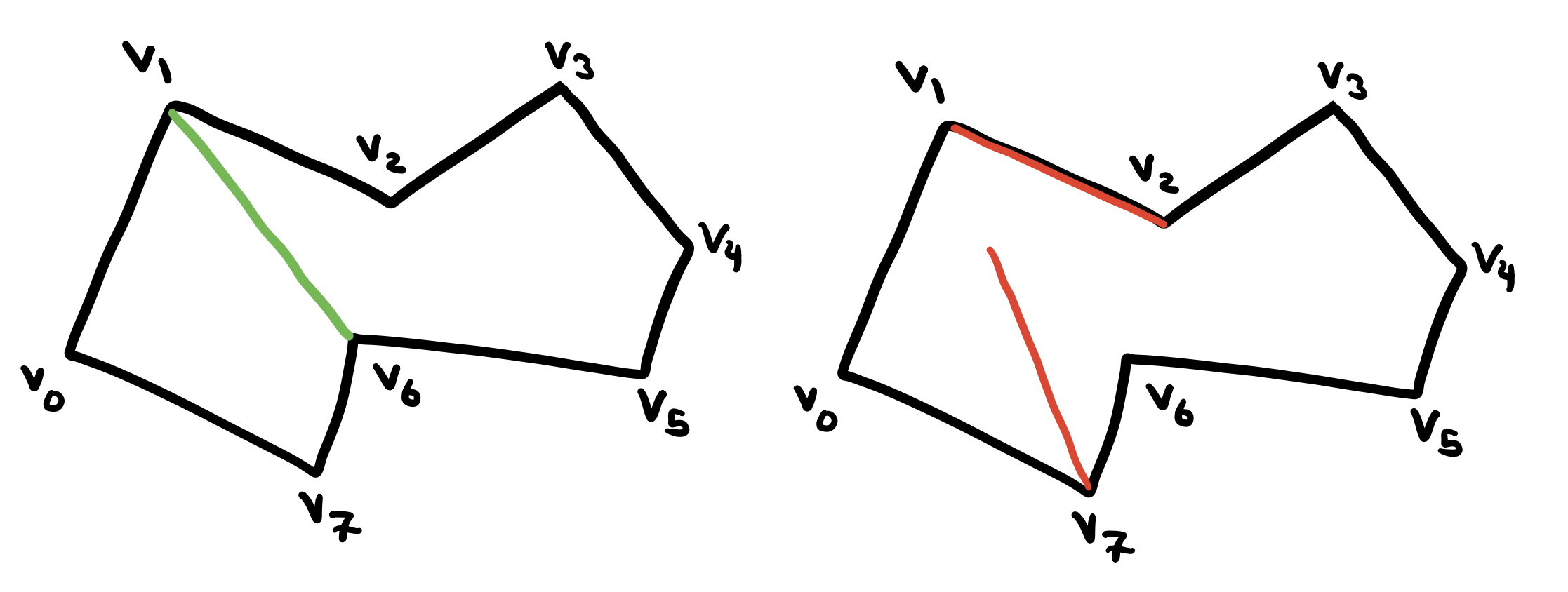

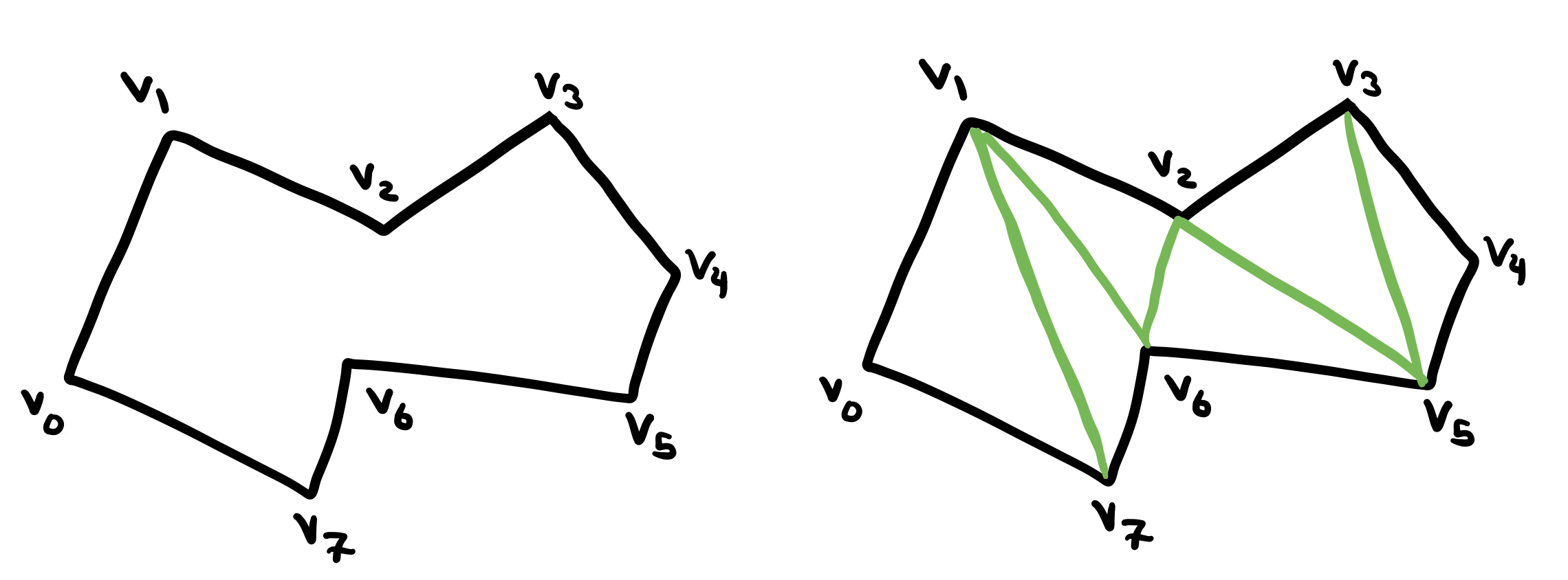

A Diagonal is a line segment between two of the polygon’s vertices \(a\) and \(b\) such that the intersection of the line segment \(ab\) with the boundary of \(P\) (\(\partial P\)) is exactly the set \(\{a,b\}\). In the first figure the segment connecting \(v_1\) and \(v_6\) is a diagonal since the intersection of the line segment with \(\partial P\) is only \(\{v_1,v_6\}\) while in the right figure none of the red line segments are diagonals. Note here that this definition applies to both internal and external diagonals!

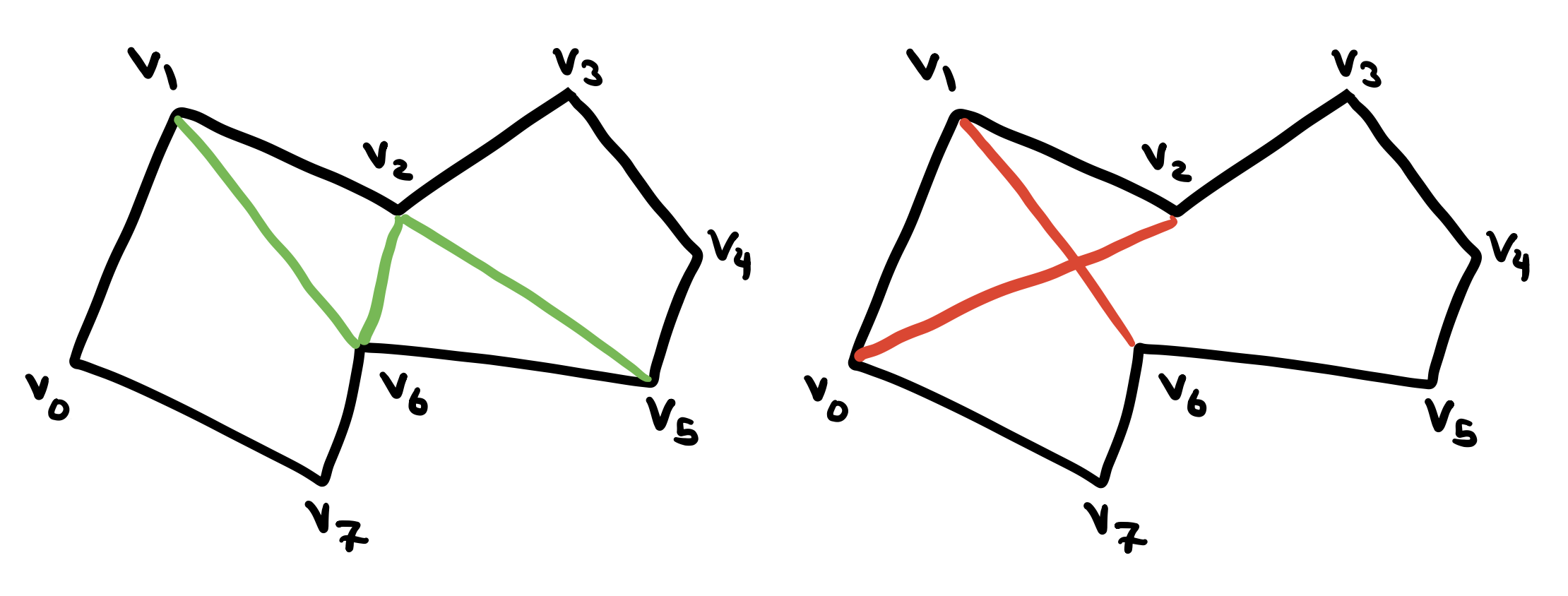

Two diagonals are non-crossing if their intersection is a subset of their endpoints. aka they share no interior points. In the left figure above, the green diagonals intersect only at their end points (if any) so they’re non-crossing while in the right figure, the red diagonals are not non-crossing since they intersect at an interior point that is not an end point of either diagonal.

Triangulation

There is one more definition that we will need for the proof later. If we add as many non-crossing diagonals as possible to a polygon, then the interior is partitioned into triangles. Such a partition is called a triangulation of a polygon. Why? This is a whole other topic an another post will be dedicated on this.

Formalizing the Art Gallery Problem

We will define \(g(P)\) to be the smallest number of guards needed to cover polygon \(P\).

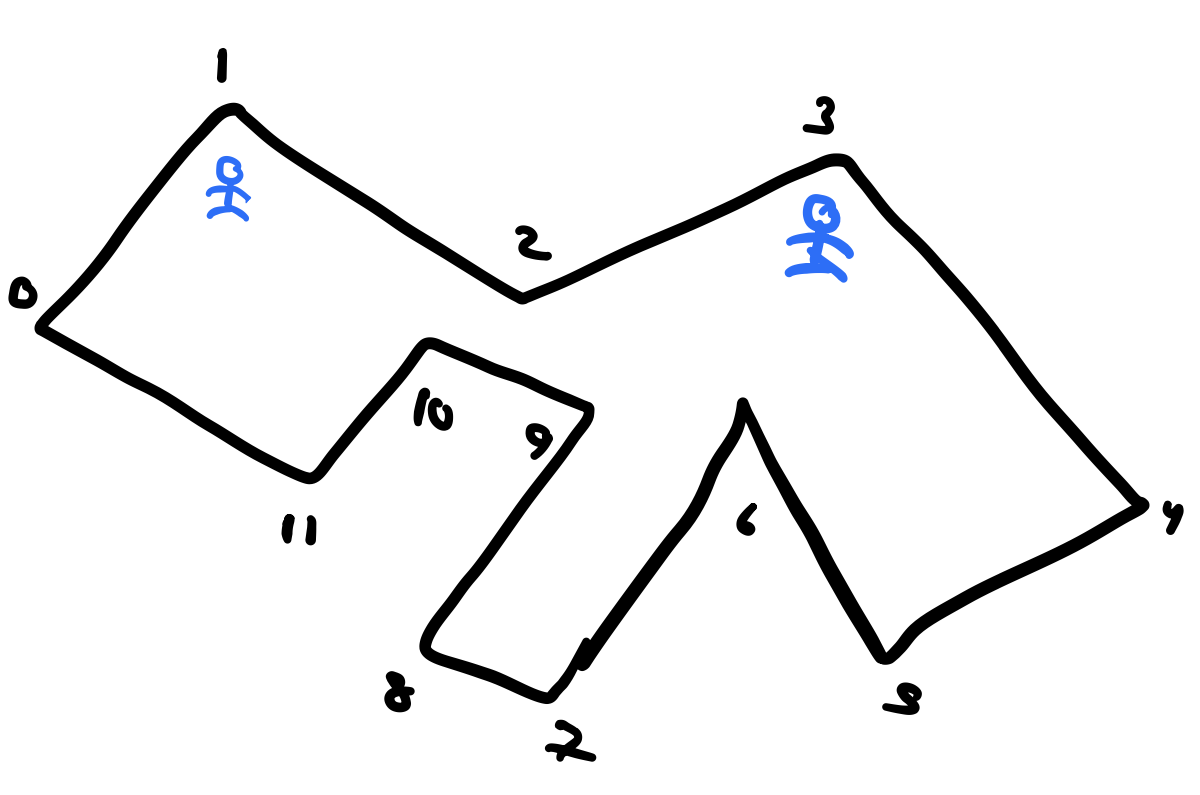

where \(S\) is a set of points and \(|S|\) is the cardinality of \(S\). \(S\) is the number of guards sufficient to cover the gallery and since many sets are possible (a triangle can be covered by a single guard or 10 guards), we’ll need to find the minimum of all these solutions. This definition works for a specific polygon given to us. For example, for the gallery below,

we’ll need 2 guards, but is this true for any polygon of \(n=12\) vertices? Absolutely not! You could instead have the following polygon with 12 vertices instead,

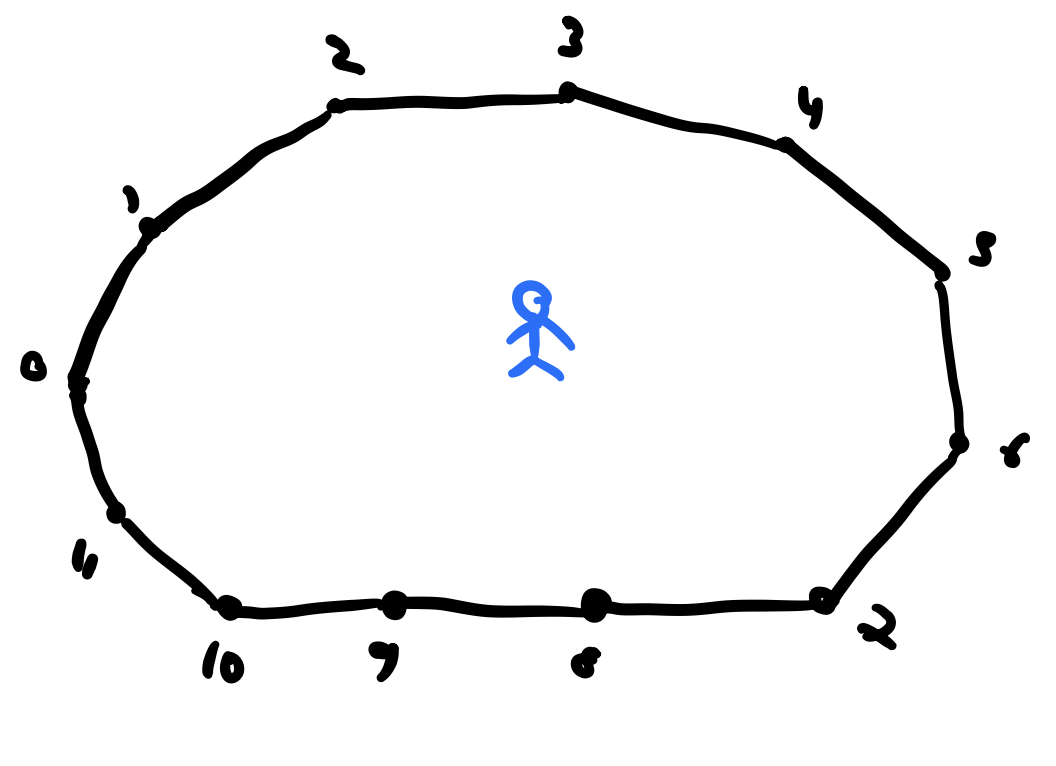

Here, it is clear that 1 guard is sufficient. What we’re interested in is number of guards sufficient for ANY type of polygon with \(n\) vertices. So let \(P_n\) be a polygon of \(n\) vertices and define

And so finally we have:

Is \(G(n)\) finite for all \(n\)? and can it be expressed with a simple formula?

Small Values of \(n\)

We can start by plugging in small values of \(n\) to see if we can find any pattern. For starters, for any polygon we will need at least 1 guard (\(G(n) \geq 1\)) and at most \(n\) guards (\(G(n)\leq n\)) (proof?).

For polygons of 3 vertices (triangles), it should be obvious that we will always need 1 guard and so \(G(3)=1\). Polygons with 4 vertices (Quadrilaterals) can be divided into two groups:

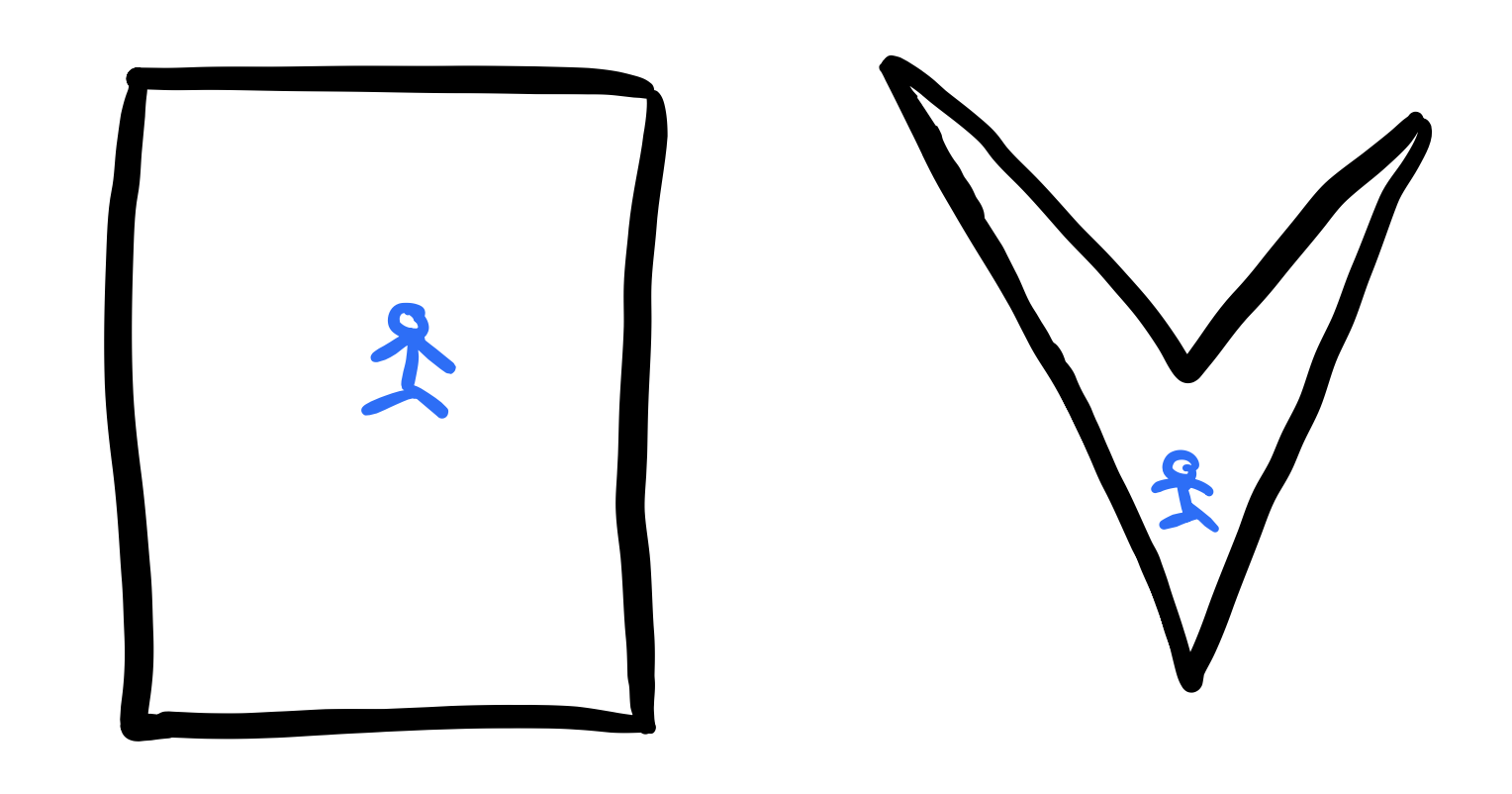

- convex quadrilaterals (left figure). Here it is clear that \(G(4)=1\).

- quadrilaterals with a reflex vertex (right figure). Recall that a reflex vertex is a vertex where its internal angle is greater that \(\pi\). A quadrilaterals can only have one reflex vertex and so one guard is still sufficient.

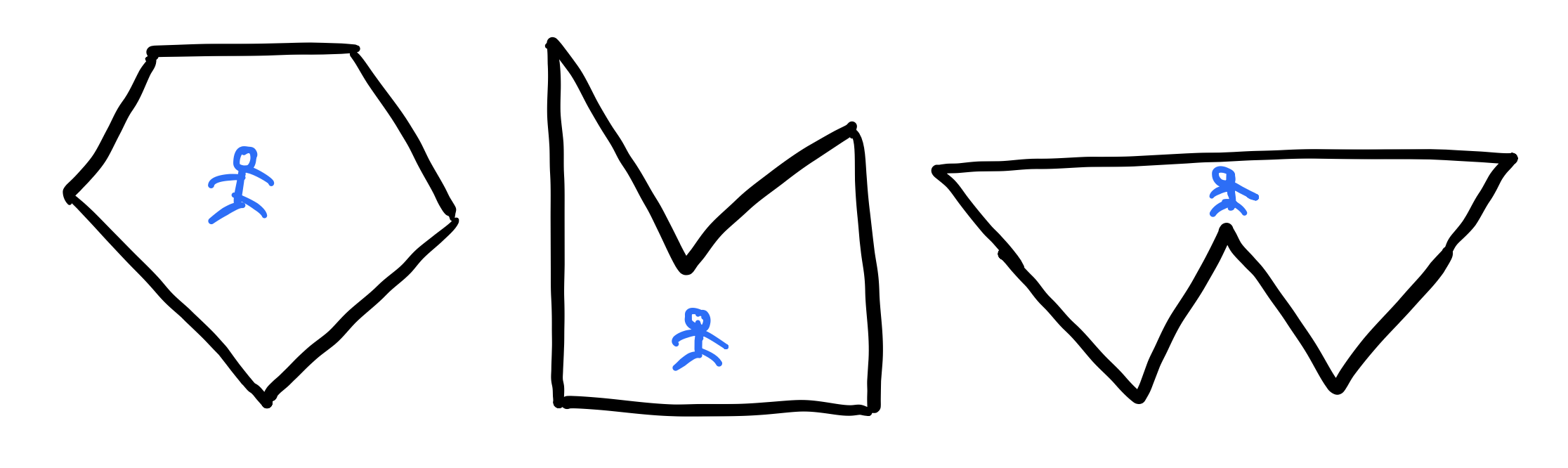

For polygons of 5 vertices (pentagons) can be divided into:

- convex Pentagons (left figure) and clearly we only need one guard.

- Pentagons with one reflex vertex (middle figure) need one guard.

- Pentagons with two reflex vertices (right figure) (pentagons can have at most two reflex vertices). These vertices can be adjacent or separated. In either case, we need one guard as well.

Fisk's Theorem

Fisk established that every Polygon with \(n\) vertices will need at least \(\lfloor n/3 \rfloor\) guards. In this section, we will outline the proof.

Proof Outline

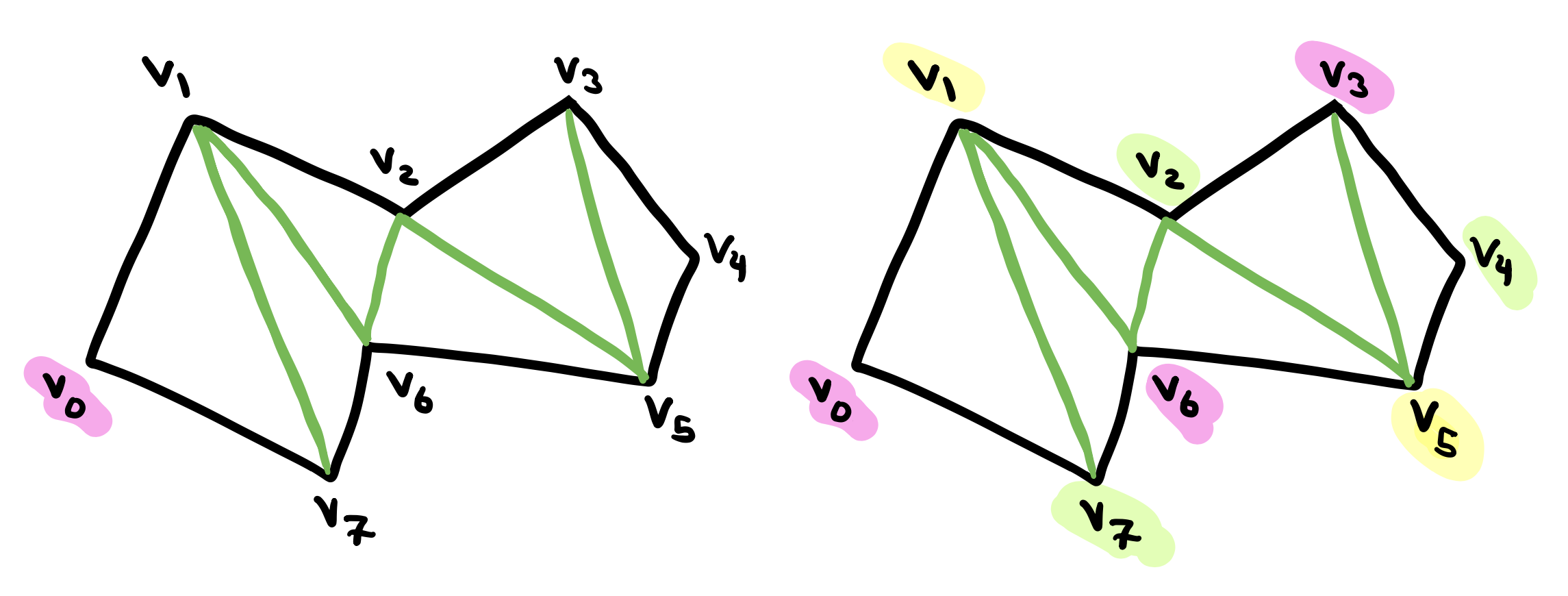

Given an arbitrary polygon \(P\) of \(n\) vertices. The first step of the proof is to triangulate the polygon by adding as many non-crossing diagonals as possible to it until the polygon is partitioned into triangles. Let the resulting graph be \(G\) such that the vertices of the polygon are the vertices of \(G\). The edges of \(G\) are the set of the original edges of the polygon plus the newly added non-crossing diagonals.

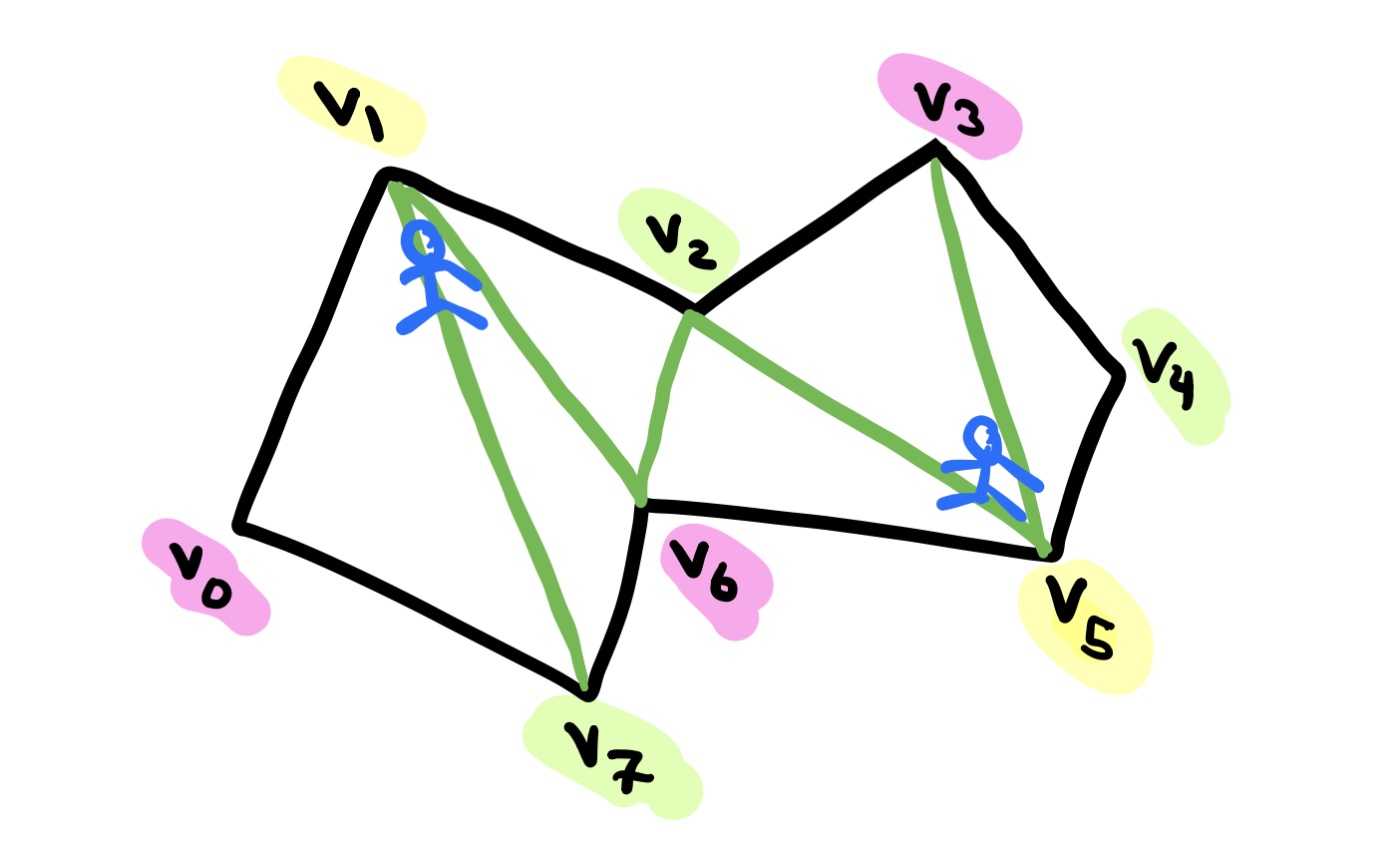

The second step is to prove that the resulting graph is 3-colored. Recall that A \(k\)-coloring of a graph is an assignment of \(k\) colors to the nodes of the graph, such that no two nodes connected by an edge are assigned the same color.. The general idea of the proof is to pick a vertex and assign it an arbitrary color. Once we do that, we will see the the coloring is completely forced. Notice that we have to choose the remaining two colors for the remaining two vertices in that triangle. Also notice that this triangle shares two vertices with the adjacent triangle and so there will not be free choices since we must choose the third remaining color for the new vertex. Hence the coloring is completely forced.

The third step of the proof is the observation that placing the guards at all the vertices assigned one color guarantees visibility coverage of the polygon. Let pink, green and yellow be the colors used in the 3-coloring of the graph. Each triangle must have each of the three colors at its three corners. This means that every triangle has a yellow (arbitrary chosen color) node and so every triangle has one guard and thus covered. We know that the collection of triangles completely cover the polygon and so this means that the whole polygon is covered.

The forth step is the application of the pigeonhole principle. Recall that the pigeonhole principle states that If \(n\) objects are placed into \(k\) polygons and \(n > k\), then at least one hole must contain no more than \(n/k\) objects. We established that we only needed 3 colors to color the triangulated graph \(G\). Now, let the \(n\) vertices of the triangulation graph be the holes and the colors of the graph (\(k=3\)) be the pigeons. Since \(n\) is an integer, then one of the color must be used no more than \(n/3\) times.