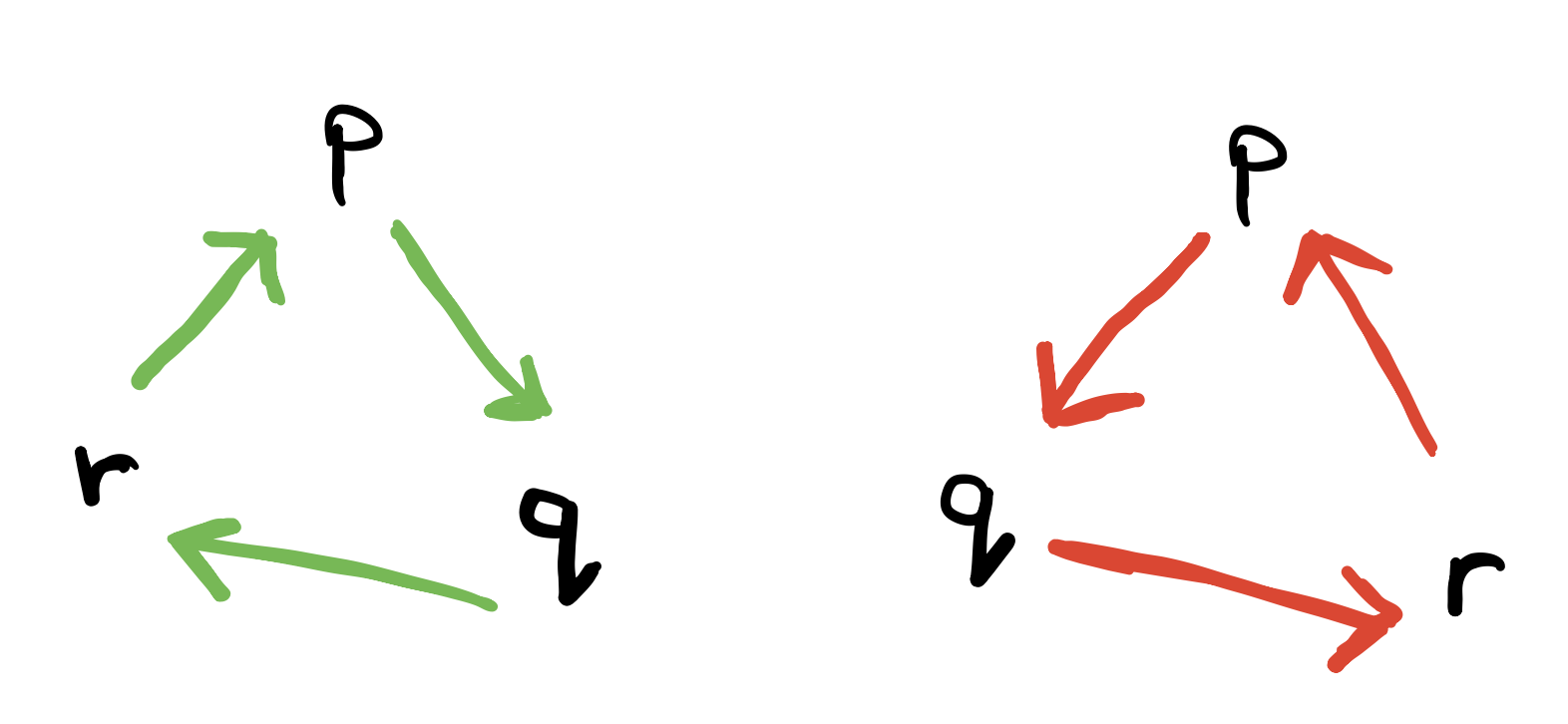

Given 3 ordered points \(p, q\) and \(r\). How do we find out the orientation of the points? What does this mean? It means that we’re visiting these points in a given specific order \(p\), \(q\) and then \(r\) and we want to know if this tranversal is clockwise, anti-clockwise or maybe these points are collinear.

Left or right of the line?

We can also ask the same question in a different way. Given three ordered points \(p\), \(q\) and \(r\). How can we tell if \(r\) is on the left or the right of the line that goes through \(pq\)? Notice in the right figure that \(r\) is on the right of the line and the ordered points \(p\), \(q\) and \(r\) have a clockwise orientation. In the right figure, \(r\) is on the left of the line and the ordered points \(p\), \(q\) and \(r\) have a anti-clockwise orientation.

Slopes to the rescue!

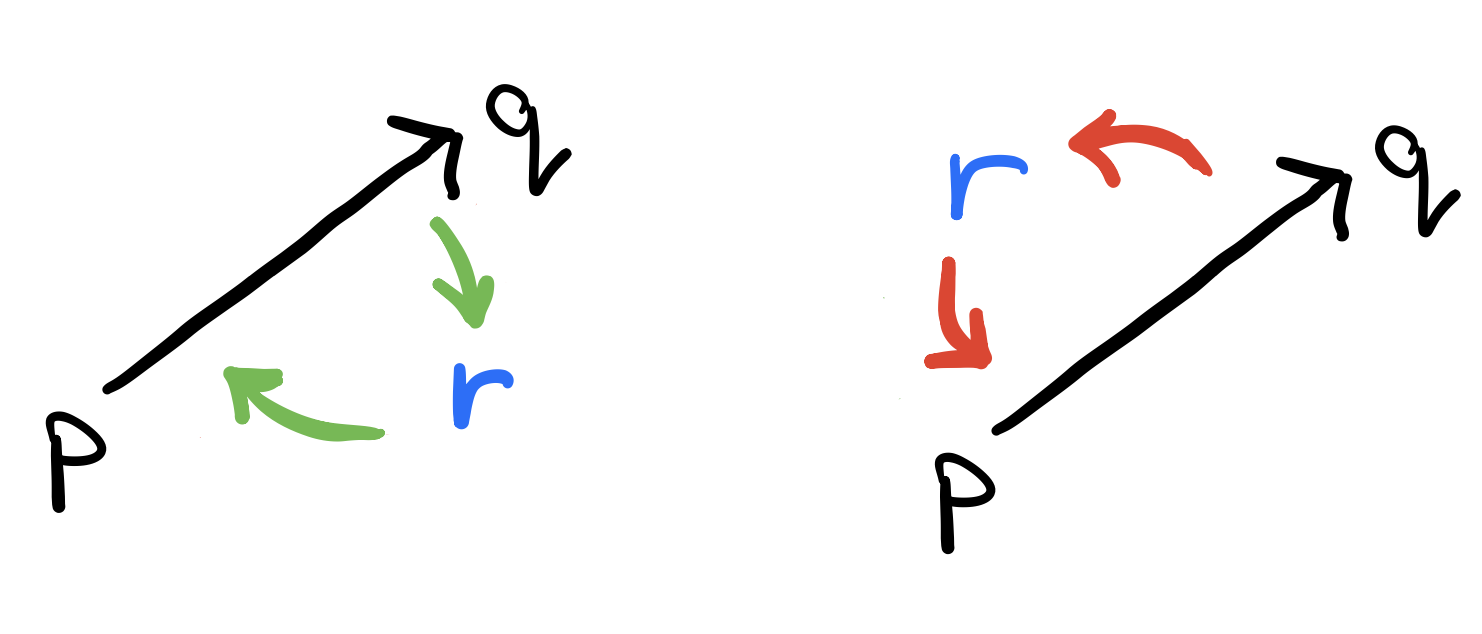

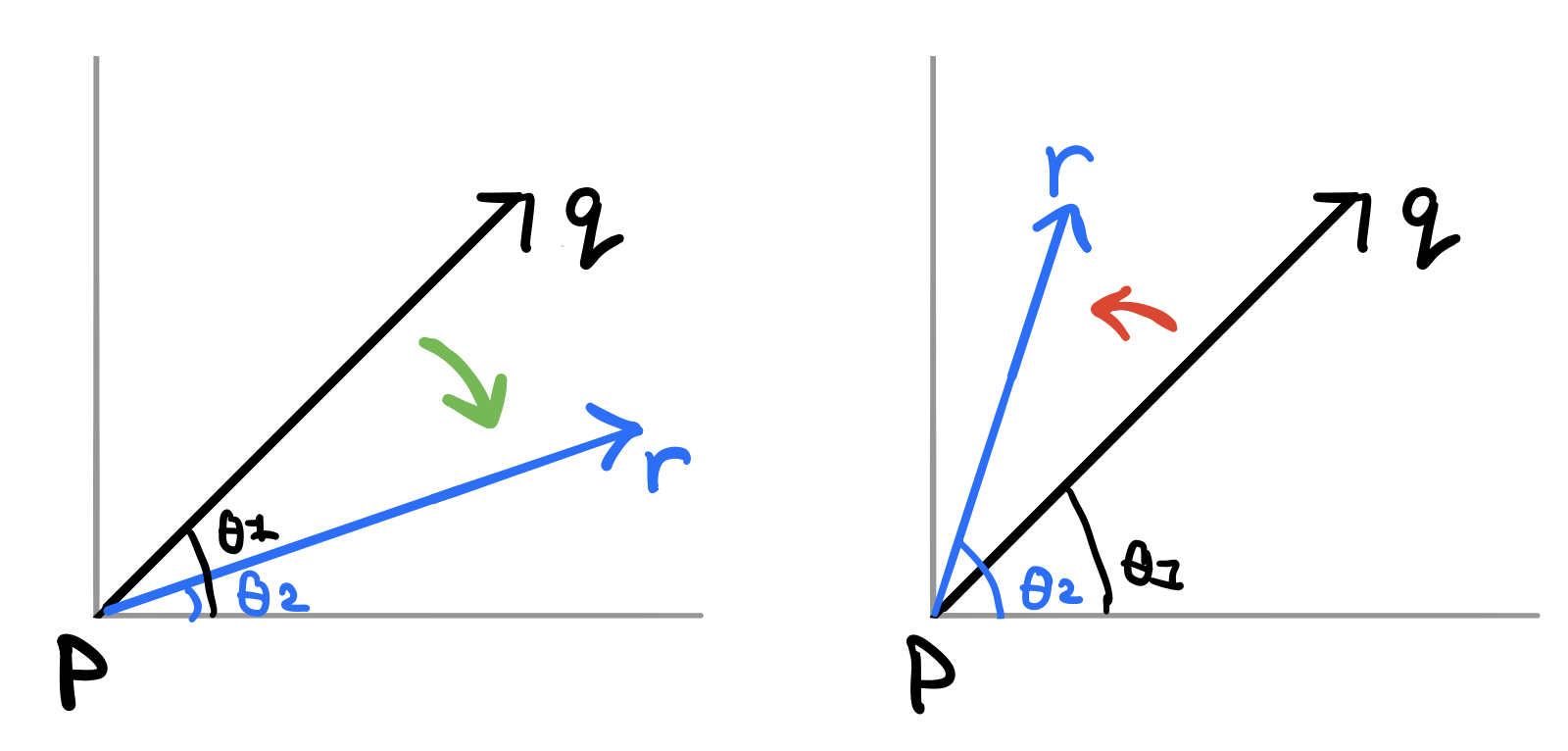

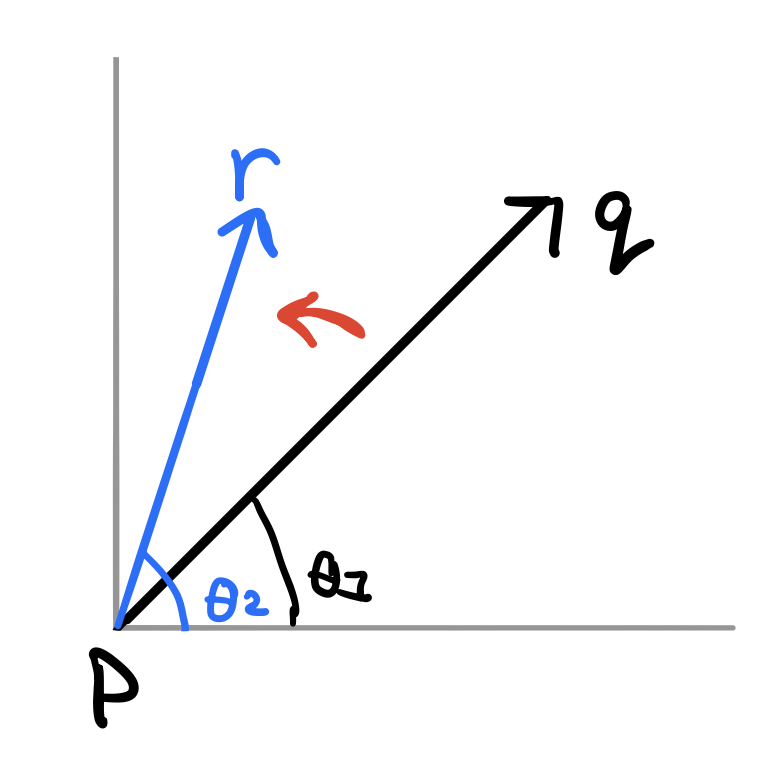

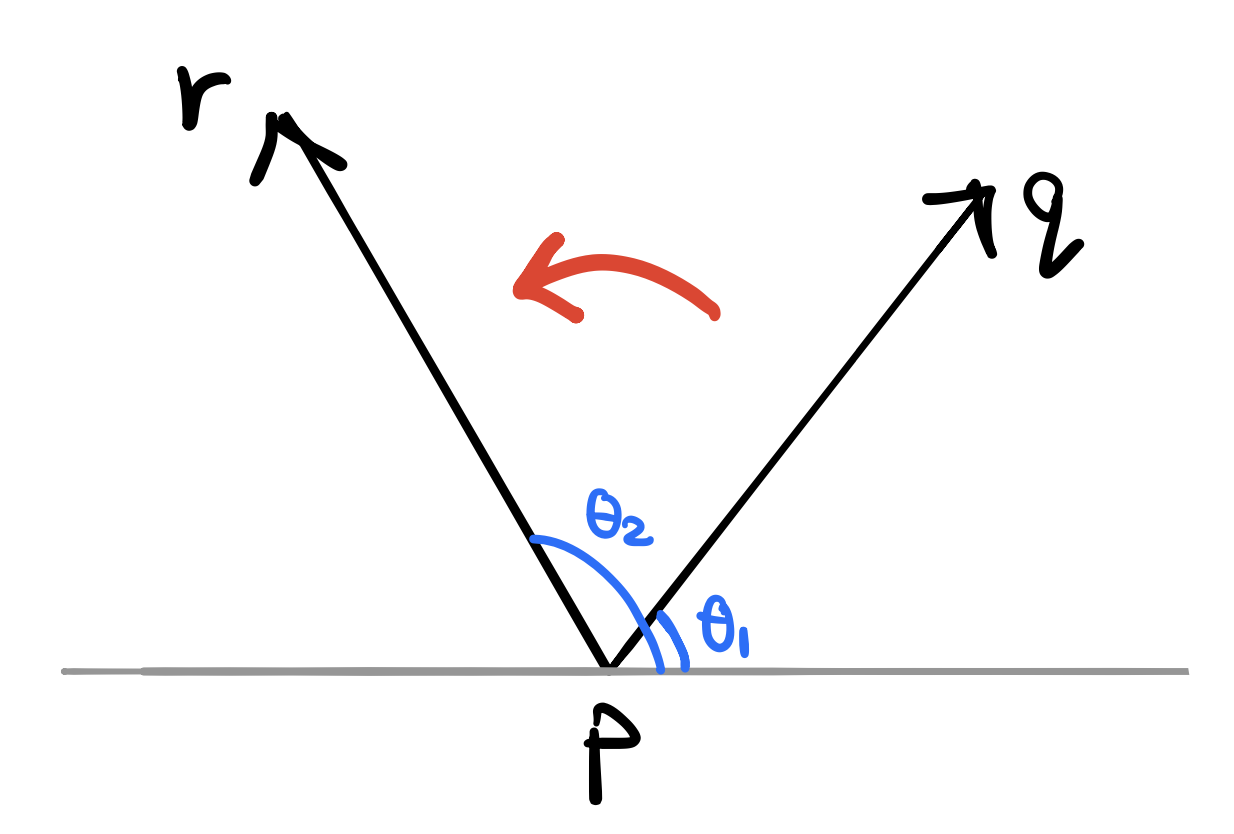

To figure this out, let \(p\) to be the left most point. Draw a line that goes through \(pq\) and then another line that goes through \(pr\). We will calculate the slope of each line to determine the line that has the biggest slope. Notice here that:

- In the left figure, the slope of the line \(pq\) is bigger than the slope of the line \(pr\) and so you can see that we're going in a clockwise order from \(p\) to \(q\) and then \(r\). You can also see that \(r\) is on the right of the line \(pq\).

- In the right figure, the slope of the line \(pq\) is smaller than the slope of the line \(pr\) and so you can see that we're going in a clockwise order from \(p\) to \(q\) and then \(r\). You can also see that \(r\) is on the left of the line \(pq\).

But do we want to calculate slopes?

Slopes are messy because of divison. Let’s focus on the right figure from the previous section and write down the slope formula. Suppose \(p=(p_x,p_y), q=(q_x,q_y)\) and \(r=(r_x, r_y)\), then

This expression is

- Greater than zero when the slope of \(pq\) is smaller than the slope of \(pr\) and so the ordered points \(p, q\) and \(r\) are in anti-clockwise orientation and \(r\) is on the left of the line \(pq\).

- Equal to zero if they're collinear.

- Less than zero when the slope of \(pq\) is greater than the slop of \(pr\) and so the ordered points \(p, q\) and \(r\) in a counter clockwise orientation and \(r\) is on the right of the line \(pq\).

Determinants!

The equation we derived in the previous section (\((q_x-p_x)(r_y-p_y) - (r_x-p_x)(q_y-p_y) > 0\)) can also be written in a nice determinat form

Cross Product

Another way to think about this is imagine that \(pq\) and \(pr\) are vectors in 3 dimensions. From linear algebra, we know that the cross product of two vectors is the signed area of the parallelogram they determine. Moreover, if \(\vec{pq} \times \vec{pr}\) is positive, then \(pr\) is anti-clockwise relative/from \(pq\) which means that \(r\) is to the left of \(pq\). The funny thing here is that to prove this statement, we just have to evaluate the cross product like we did the previous section and then work backward until we arrive at the slope form and see that \(pr\) has the bigger slope and hence \(r\) is on the left of \(pq\)!