(1) My study notes from CS109 http://web.stanford.edu/class/archive/cs/cs109/cs109.1188/

(2) First Course in Probability by Sheldon Ross.

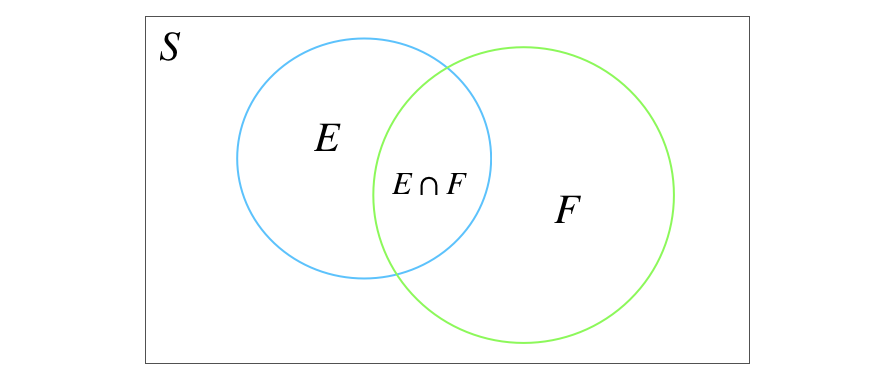

Conditional probability is the probability that event \(E\) occurs given that event \(F\) has already occured written as \(P(E|F)\). In this case:

- The sample space consists of all possible outcomes consistent with \(F\) (events in \(S \cap F\)).

- The event space consists of all possible outcomes in \(E\) that are consistent with \(F\) (events in \(E \cap F\)).

Therefore, we have in general

And for equally likely outcomes:

From the conditional probability law, we can derive the chain rule!

And in general if we have multiple events:

Example:

Suppose we have an urn with 8 red balls and 4 white balls. What is the probability of choosing two balls that are both red (without replacement). (Source: A First Course in Probability)

Let \(E_1\) to be the event that the first ball is red.

Let \(E_2\) to be the event that the second ball is red.

In general:

The law of total probability says that the probability of event \(E\) is now a weighted average of the conditional probability of \(E\) given event \(F_1\) plus the conditional probability of \(E\) given event \(F_2\) and so on. Note that these events \(F_i\) must be mutually exclusive. Moreover, \(\sum_iP(F_i) = 1\).

Example:

Suppose 25% of students are juniors. Suppose now that if a student is a junior then the probability of being a CS major is 30%, while if a student is not a junior then the probability of being a CS major is 20%. What is the probability of being a CS major? (Class Example)

Let \(CS\) to be the event that a student is a CS major.

Let \(J\) to be the event that a student is a junior.

Common Form:

Expanded Form:

Example:

A test is 98% effective at detecting HIV. The test has a false positive rate of 1%. 0.5% of the US population has HIV. What is the probability that you have HIV given that you tested positive? (class example)

Let \(E\) be that you test positive for HIV with the test

Let \(F\) be that you actually have HIV.

We want to find \(P(F|E)\)?

First, the probability that the test is positive given that you actually have HIV is 0.98 (true positive). In terms of \(E\) and \(F\), this is \(P(E|F)=0.98\). Similarly, the probability that we get a false positive is 0.01. In terms of \(E\) and \(F\), this probability is \(P(E|F^c)\),

We can now use Bayes’

Suppose we have 3 doors. Behind one of the three doors a prize. We choose a door. The host then opens one of the remaining doors that reveals nothing. We are now given the chance to switch our door with the remaining door. Do we switch?

We want to compare \(P(win)\) vs \(P(win|switch)\). We know that if stick with our door, \(P(win)=1/3\).

Suppose without the loss of generality that we picked door \(A\). What is the probability that we win given that we switched? Let’s consider what happens if we switch in each case.

Let \(A, B\) and \(C\) be the events that the prize is behind each door respectively. All three doors are equally likely and so each door has a probability of \(1/3\). Moreover, these events are mutually exlusive since the prize can be behind exactly one door. Also the probability of these events sum up to 1.

Prize behind door \(A\):

In this case the host will open either door \(B\) or \(C\). We will switch and lose. So, \(P(win | \text {switch to B/C}) = 0\).

Prize behind door \(B\):

In this case the host will open door \(C\). We switch and we win! \(P(win| \text {switch to C})=1\).

Prize behind door \(C\):

In this case the host will open door \(B\). We switch and we win! \(P(win| \text {switch to B})=1\).

Using the law of total probability: