Let \(G=(V,E)\) be an undirected graph with \(V\) vertices and \(E\) edges. A cut in \(G\) is a partition of \(V\) into two non-empty sets of vertices \(A\) and \(B\). The size of the cut is the number of edges with one end point in \(A\) and another in \(B\). A global minimum cut is a cut of minimum size.

Let \(G=(V,E)\) be an undirected graph with \(V\) vertices and \(E\) edges. A cut in \(G\) is a partition of \(V\) into two non-empty sets of vertices \(A\) and \(B\). The size of the cut is the number of edges with one end point in \(A\) and another in \(B\). A global minimum cut is a cut of minimum size.

Karger's Algorithm

Karger’s algorithm starts with picking an edge \((u,v)\) in \(G\) uniformly at random. It then contracts this edge by creating a new node \(w\) that combines both \(u\) and \(v\). All the edges in \(G\) with an end point equal to either \(u\) and \(v\) now point to \(w\) instead. Also, any edge between \(u\) and \(v\) is deleted. It repeatedly contracts randomly picked edges until we have two vertices in the graph. We then return the number of edges between the two vertices as the global minimum cut in \(G\).

Karger's Algorithm Pseudocode

void karger(graph& g) {

Initially create a set for each node v, S(v) = {v}

while (G has more than two nodes) {

choose an edge e=(u,v) uniformly at random.

create a new node w with S(w) = S(u) union S(v)

}

return the sets of the last two nodes.

}

Example

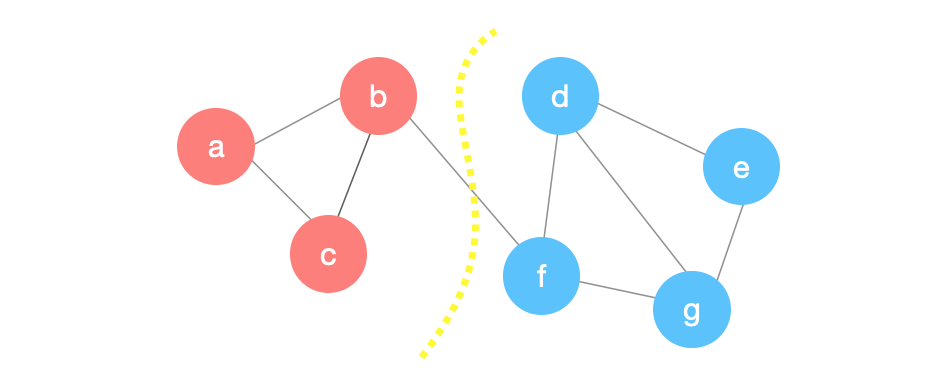

In this example, we will apply the contraction algorithm above on the following graph. We start by picking an edge uniformly at random. Suppose we picked the edge \((d,e)\) below:

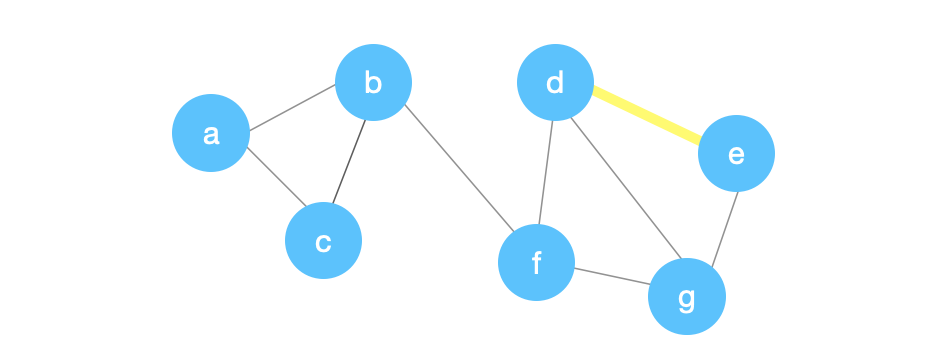

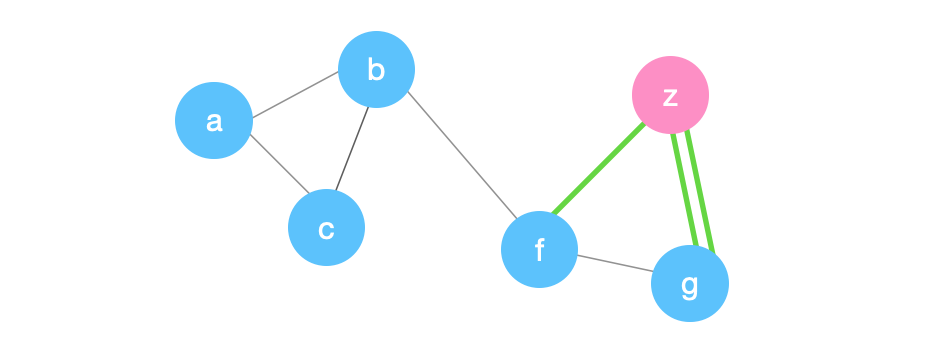

We then delete \((d,e)\). We create a new node \(z\). We then point any edge that previously had an end point equal to \(d\) or \(e\) to point at \(z\) instead.

We then delete \((d,e)\). We create a new node \(z\). We then point any edge that previously had an end point equal to \(d\) or \(e\) to point at \(z\) instead.

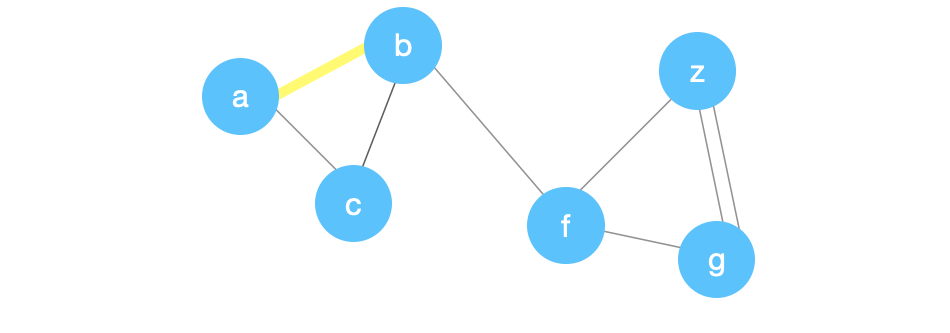

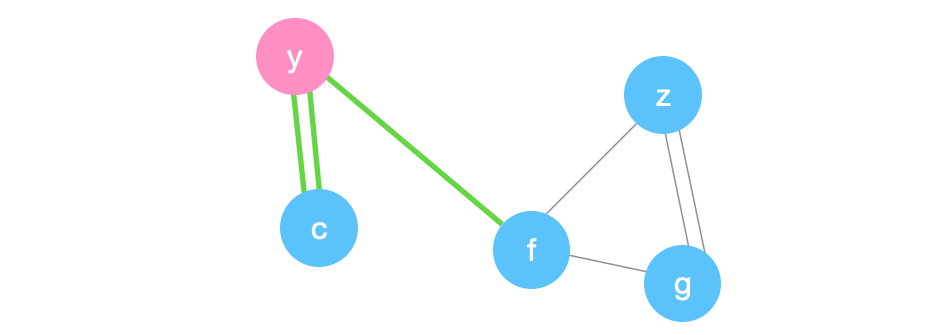

Suppose we pick \((a,b)\) next.

Suppose we pick \((a,b)\) next.

We delete \((a,b)\) and create node, \(y\), and fix all the old edges pointing at \(a\) or \(b\) to point at \(y\).

We delete \((a,b)\) and create node, \(y\), and fix all the old edges pointing at \(a\) or \(b\) to point at \(y\).

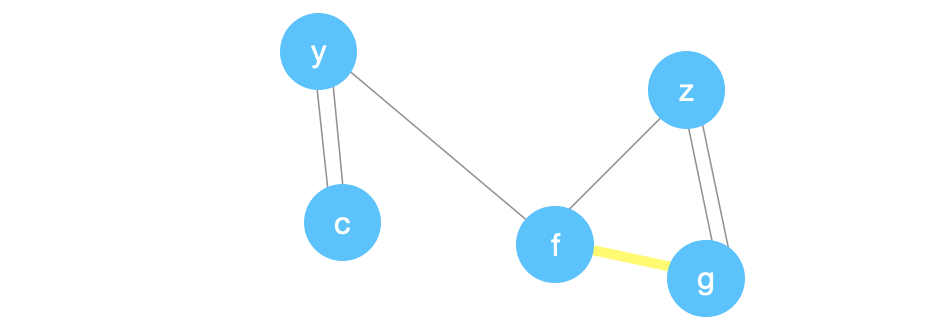

Suppose we pick \((f,g)\) next.

Suppose we pick \((f,g)\) next.

We’ll repeat the same process by creating node, \(x\), and fixing the edges below.

We’ll repeat the same process by creating node, \(x\), and fixing the edges below.

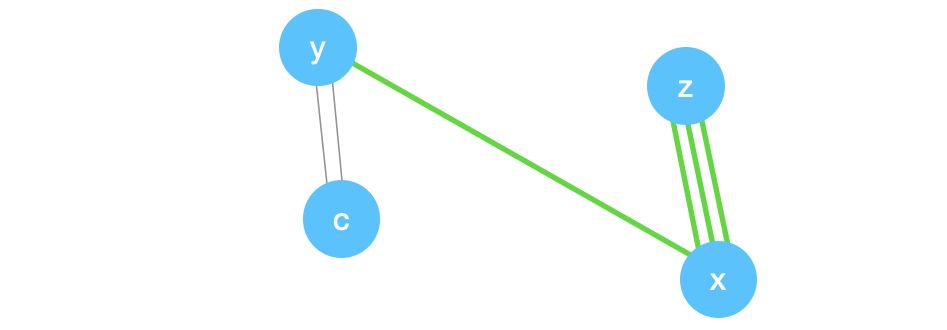

Suppose we pick \((z,x)\) next.

Suppose we pick \((z,x)\) next.

We’ll delete \((z,x)\), create a new node, \(w\), and fix all the edges below.

We’ll delete \((z,x)\), create a new node, \(w\), and fix all the edges below.

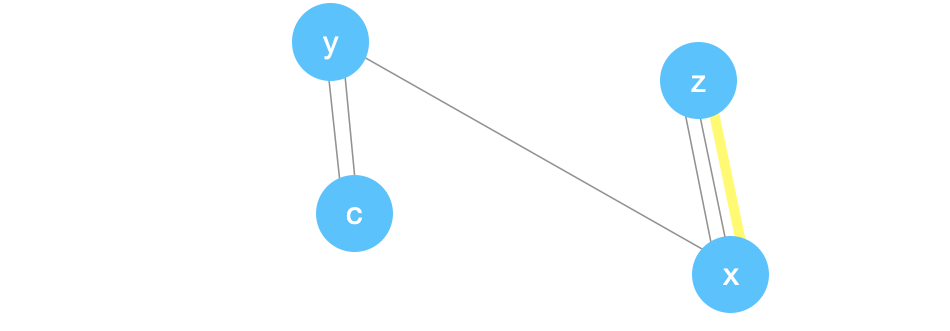

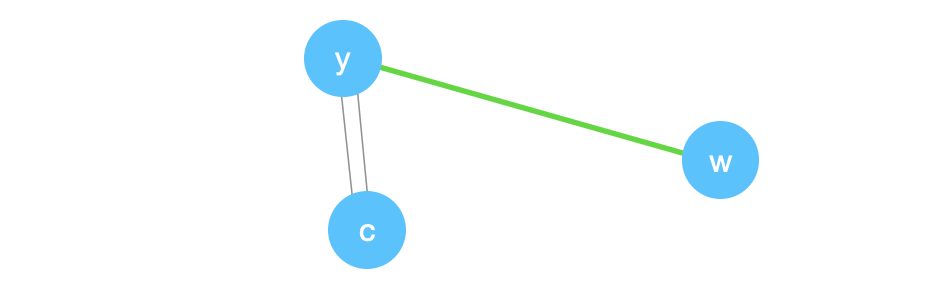

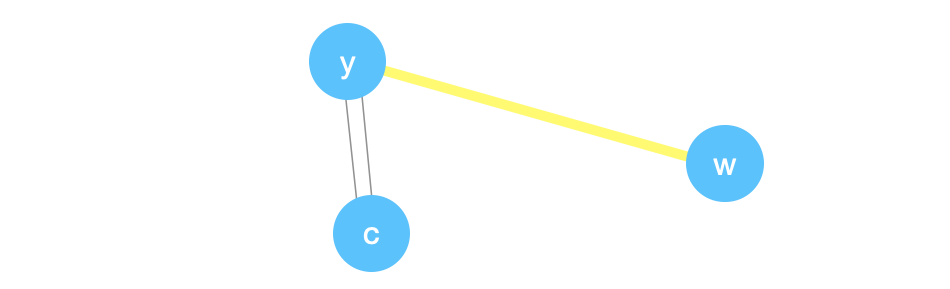

Finally, we have two edges left. Each edge has a 0.5 probability of being picked up. Suppose we pick \((y,c)\).

Finally, we have two edges left. Each edge has a 0.5 probability of being picked up. Suppose we pick \((y,c)\).

Since we only have 2 vertices then we’re done. We will return the number of edges between the two vertices which is 1 in this case. So the global minimum cut is of size 1 which is correct for this graph.

Since we only have 2 vertices then we’re done. We will return the number of edges between the two vertices which is 1 in this case. So the global minimum cut is of size 1 which is correct for this graph.

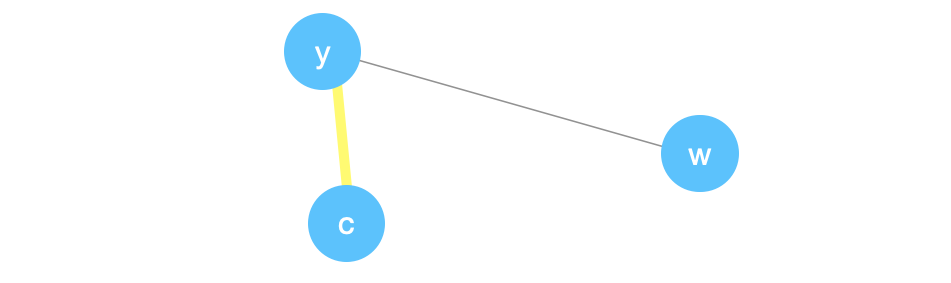

Suppose however that instead of picking \((y,c)\) to contract, we picked \((y,w)\).

Suppose however that instead of picking \((y,c)\) to contract, we picked \((y,w)\).

We will end up with a global minimum cut of size 2 instead which is not correct for this graph! This is why Krager’s algorithm is a Monte Carlo algorithm.

We will end up with a global minimum cut of size 2 instead which is not correct for this graph! This is why Krager’s algorithm is a Monte Carlo algorithm.

Probability of Success

Suppose we have a graph \(G=(E,V)\) with \(n\) nodes and \(m\) edges. Suppose the cut \((A,B)\) is a global minimum cut is of size \(k\). Also, let \(F\) to be the set of \(k\) edges in the cut \((A,B)\). So \(F\) has the edges that have one end point in \(A\) and the other end point in \(B\).

The probability that the contraction algorithm succeeds is the probability that we don’t make any mistake in the \(n-2\) iterations of the algorithm. Suppose we let \(S_i\) to be the event that we don’t make a mistake in step \(i\) or generally succeed in step \(i\). We want to calculate the following probability:

These events are not independent! We can further expand this using the chain rule and instead calculate:

Success in the iteration 1:

Let’s look at how we can calculate each of these. What does it mean to not make a mistake in step 1? It means that we don’t pick an edge that connects a vertex from the set \(A\) to a vertex from the set \(B\). Because if we did, then \(A\) and \(B\) will be merged together and we will not be able to return the global minimum cut \((A,B)\). So we basically want to avoid picking edges from \(F\). Therefore, the probability that we don’t make a mistake in step 1 is

What is \(|E|\)?

We will use \(k\) to find an upper bound on \(|E|\). We know that the global minimum cut is of size \(k\), therefore, we must have:

| For any node \(v\) in \(V\), \(degree(v) \geq k\) |

Proof: Suppose not, then there exists some node \(u\) such that \(degree(u) < k\). Pick the minimum cut such that \(A = \{u\}\) and \(B = V - \{u\}\). The cut \((A,B)\) is a global minimum cut of size less than \(k\) which is a contradiction. \(\blacksquare\)

Based on this, we can conclude that \(|E| \geq \frac{1}{2}kn\). (\(\frac{1}{2}\) because \(G\) is undirected).

So now we have:

Success in iteration \(i+1\):

What about the other iterations? What is the probability that we don’t make a mistake in iteration \(i+1\) given that we haven’t made any mistake in all the previous interations? At iteration \(i+1\), we have \(n-i\) nodes in the graph. Since we haven’t made any mistake yet, we still have \(k\) edges in \(F\) and each node is of degree at least \(k\) (same proof as before). Therefore,

Now we can combine everything together:

Can we do better?

The probability of success, \(p\), we found so far is

Suppose we run \(T\) trials of Krager’s algorithm. We then take the minimum cut of all cuts found. These trials are independent. What is the probability of NOT getting the global minimum cut? It is the probability of failing in every trial. Let \(F_i\) be the event that we failed to find the global minimum cut in iteration \(i\). Therefore,

We also know that for any \(x \geq 1\), we have

Suppose we let \(x = \frac{1}{p}\), we see that

This is exactly our expression above with \(T = \binom{n}{2}\). Furthermore, we can let \(T = \ln(n)\binom{n}{2}\) to get

In general, if we want the probability of failure to be at most \(\delta\) then we need to set \(T\) to \(\ln(1/\delta)\frac{1}{p}\) in

This is because

Running Time

Suppose we have \(n\) nodes and \(m\) edges. In the naive implementation, we contract \(n-2\) edges until we reach a graph with 2 vertices. Every time we contract an edge, we need to create a new node and also correct all the edges connected to either end of the contracted edge. This could take \(O(n)\) time. Therefore, the total running time is \(O(n^2)\). There are other faster implementations with union-find data structure that reduce the running time to \(O(m * \alpha(n))\). (TODO: More on this?)

Given that we can get a high success probability if we run Krager’s algorithm for \(O(\log(n)n^2)\). The total running time is therefore \(O(n^4\log(n))\)!

Karger - Stein

Can we do better than \(O(n^4\log(n))\) and still maintain a high success probability? Krager and Stein published an improved result that’s much faster!

Observe when running Krager’s algorithm is that the probability of picking the wrong edge (an edge from the edges crossing the cut, the set \(F\)) gets higher with every iteration. Therefore, we should really just run karger once in the first few iterations and then repeat Karger for the remaining nodes.

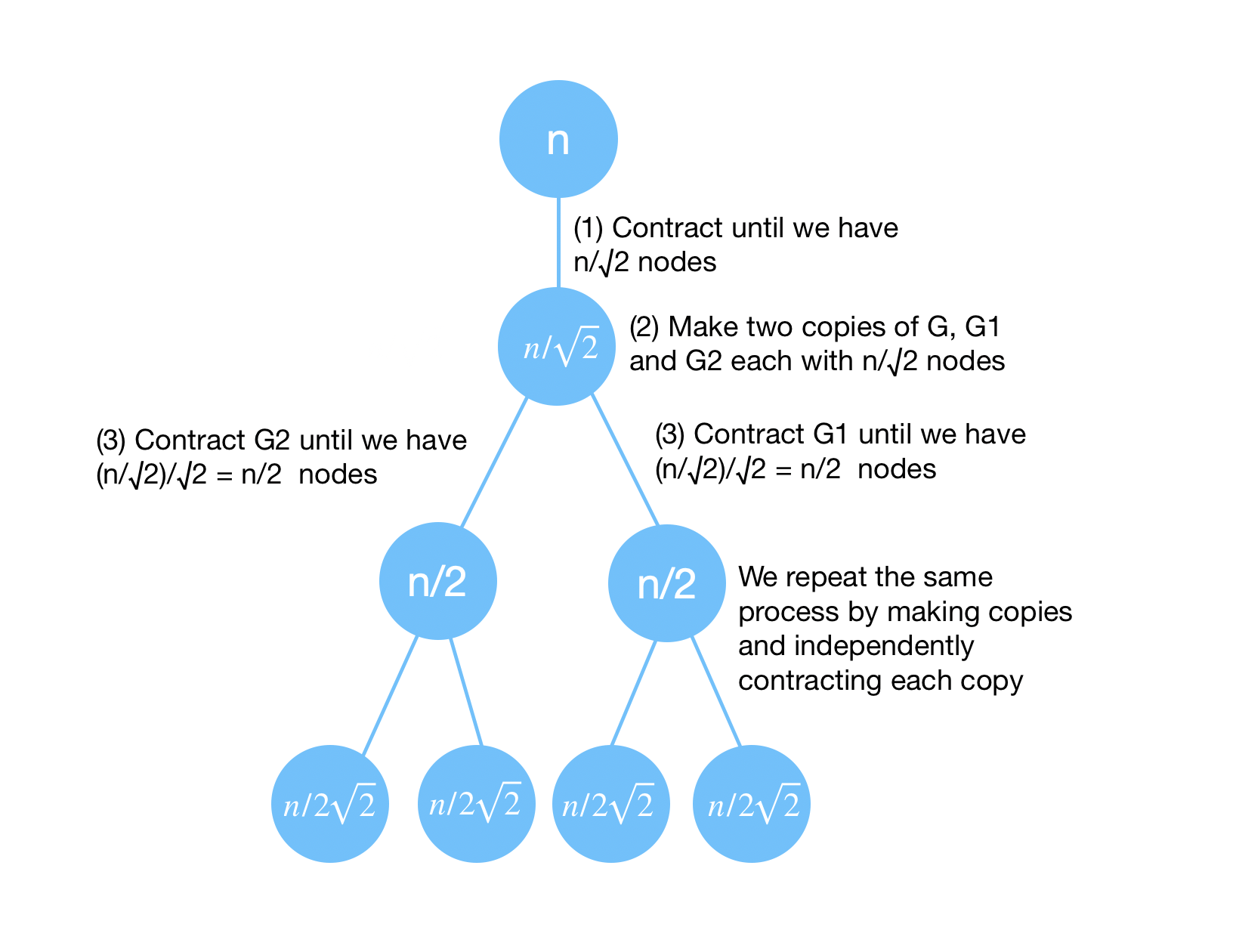

This is what Karger-Stein’s algorithm is doing. We contract edges until we get \(n/\sqrt{2}\) vertices. We then make copies of the graph and independently contract the edges again for each graph until we get to \(n/\sqrt{2}/\sqrt{2}\). We then return the minimum of both cuts. We repeat this process again until we reach 4 vertices and simply find the minimum cut by brute force. This is illustrated in the below graph:

We also summarize it in the following pseudo-code:

We also summarize it in the following pseudo-code:

void karger_stein(graph& g) {

if (n < 4) {

find a minimum cut by brute force

}

Karger(g); Contract edges until there are only n/sqrt(2) nodes left

Let g1 = g and g2 = g (two copies)

cut1 = karger_stein(g1)

cut2 = karger_stein(g2)

Return the minmum cut of cut1 and cut2

}

Karger - Stein Running Time

Karger-Stein is a recursive algorithm. At each level of the recursion, we perform Karger on \(G\) until we reach \(n/\sqrt{2}\) vertices. Karger runs in \(O(n^2)\). Therefore, we have the following recurrence for the running time:

And therefore, the running time is \(O(n^2\log(n))\) by the master theorem.

Karger - Stein Probability of Success

Karger-Stein first contracts the graph from \(n\) vertices down to \(n/\sqrt{2}\) vertices. Similar to the analysis we did earlier. The probability of success is the probability of not picking the wrong edges in any of the first \(n-n/\sqrt{2}\) iterations. Therefore, combining all probabilities:

If represent these probabilities with a binary tree then we know at each step we have a probability of \(1/2\) of picking the right path down to a leaf. Since we’re dividing by \(\sqrt{2}\), then we know that the depth of the tree is

And the number of leaves is

To find the overall probability of success, we need to find the probability of picking the right path from the root down to a leaf. Picking the right path means that at every step we pick the right edge. Suppose \(x\) is a vertex in this tree and let \(d\) be the height of \(x\). Let \(p_d\) be the probability that there exists a path of surviving edges from \(x\) down to a leaf. Let \(L\) be the event that there exists a path of surviving edges in the left subtree of \(x\). Let \(R\) be the event that there exists a path of surviving edges in the right subtree of \(x\). We see that

The claim is that \(p_d \geq \frac{1}{d+1}\). To see this, we need to prove this by induction by \(d\) for \(d > 0\).

For the base case, the probability of finding a path of surviving edges when the height is 0 is 1. We also see that \(p_0 \geq \frac{1}{0+1} = 1\) as we wanted to show.

For the inductive hypothesis, suppose it holds for \(d-1\) and so \(p_{d-1} \geq \frac{1}{d}\). We will prove that it holds for \(d\).

Side Note: I don’t know how I would come up with replacing \(1/d^2\) with \(1/d(d+1)\).

Finally since the root of the tree has depth \(2\log(n)\), then we know that the probability of success is at least \(\frac{1}{2\log(n)+1}\).

Karger - Stein Improved Success Rate

But how many trials do we need in order to achieve the same success rate as Karger’s original algorithm (with repetition)? We know the probability of success is at least \(p = \frac{1}{2\log(n)+1}\). The probability of failing in \(T\) trials (trials are independent) is the following if we set \(T\) to \(\ln(1/\delta)\frac{1}{p}\)

We arrived at this in the previous analysis of Karger’s algorithm. Therefore, we set \(T = (2\log(n)+1)\ln(1/n)\) to get a probablity of failure to be at most \(\frac{1}{n}\).

References

class notes from following:

- http://web.stanford.edu/class/cs161/schedule.html

- https://web.stanford.edu/class/archive/cs/cs161/cs161.1138/lectures/11/Small11.pdf

- http://web.stanford.edu/class/archive/cs/cs161/cs161.1172/CS161Lecture16.pdf

- Algorithm Design (BEST BOOK)