Suppose we want to ship oranges from NYC to SF. We have different routes of different capacities. The total number of oranges entering some city \(a\) must be equal to the number of the oranges leaving \(a\). In other words, cities can’t withhold oranges. We want to find the maximum number of oranges we can ship to SF. This is just one example where we would use a flow network to solve the problem.

Flow Networks

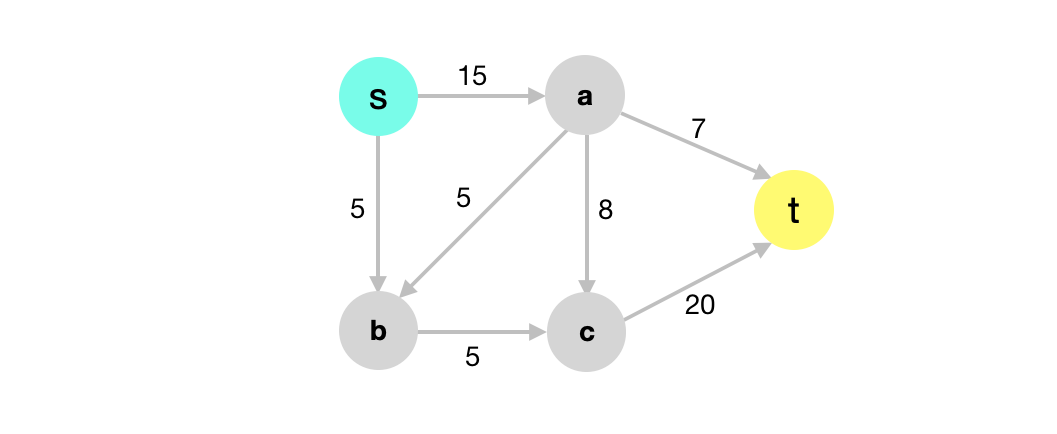

A flow network \(G=(V,E)\) is a directed graph where

A flow network \(G=(V,E)\) is a directed graph where

- We have two distinguished vertices, the source vertex \(s\) and the sink vertex \(t\).

- Each edge \((u,v) \in E\) has a non-negative capacity \(c(u,v) \geq 0\). (edge labels above)

- If we have edge \((u,v) \in E\) then we must have \((u,v) \not\in E\).

- For any vertex \(v \in V\), \((v,v) \not\in E\).

- \(G\) is connected and so \(|E| \geq |V| - 1\).\(\)

What is Flow?

A flow is a real valued function \(f : V \times V \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\). We say \(f(u,v)\) is a flow from vertex \(u\) to vertex \(v\) or the flow carried by the edge \((u,v)\). \(f(u,v)\) must satisfy:

A flow is a real valued function \(f : V \times V \rightarrow \mathbb{R}\). We say \(f(u,v)\) is a flow from vertex \(u\) to vertex \(v\) or the flow carried by the edge \((u,v)\). \(f(u,v)\) must satisfy:

(1) Capacity constraint: For all \(u, v \in V\), we require

In other words, the flow on every edge must not exceed its capacity.

(2) Flow Conservation: For all \(u \in V - \{s,t\}\), we require

In other words, the total flow coming into \(u\) is equal to the total flow leaving \(u\). Nodes don’t withhold flow.

Flow Value

Let \(|f|\) be the value of the flow defined as

In other words, the flow value is the total flow coming out of the source minus the total flow coming into the source. Notice how the flow value is a natural upper bound on the maximum flow we can push from \(s\) to \(t\). Algorithm Design uses the notation \(v(f)\) instead of \(|f|\).

The Maximum Flow Problem

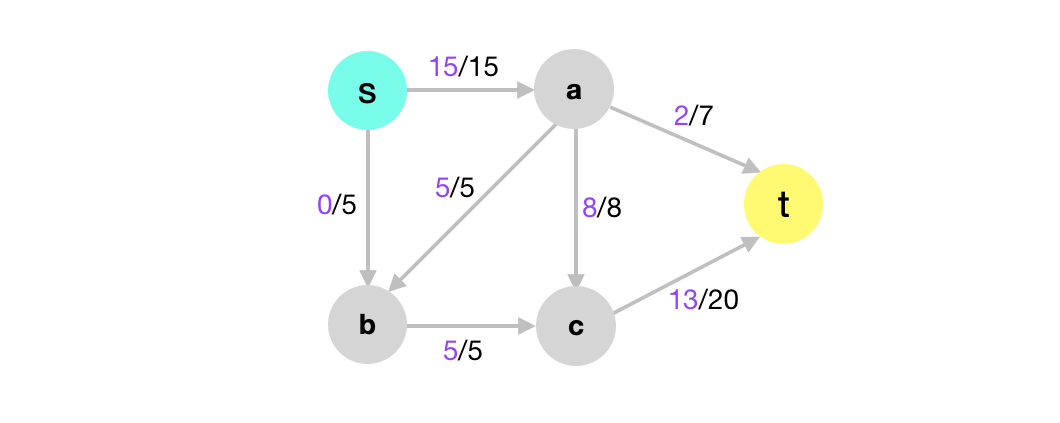

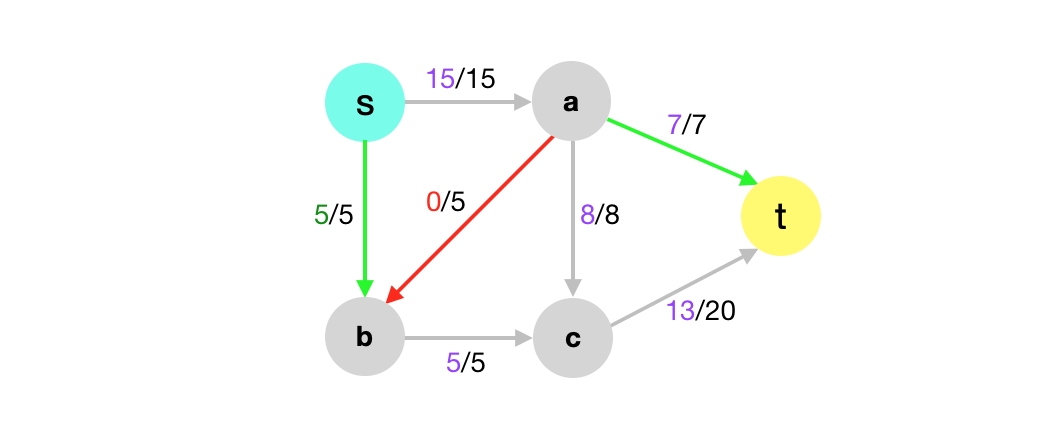

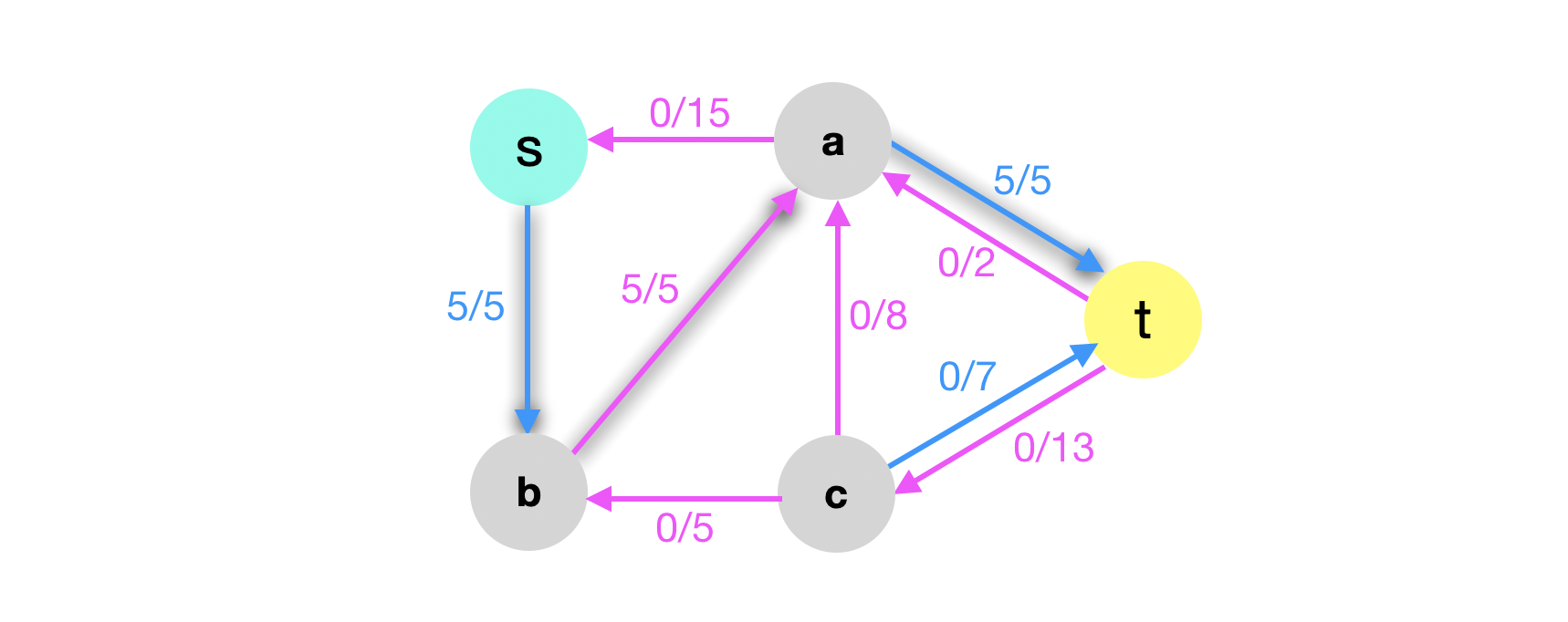

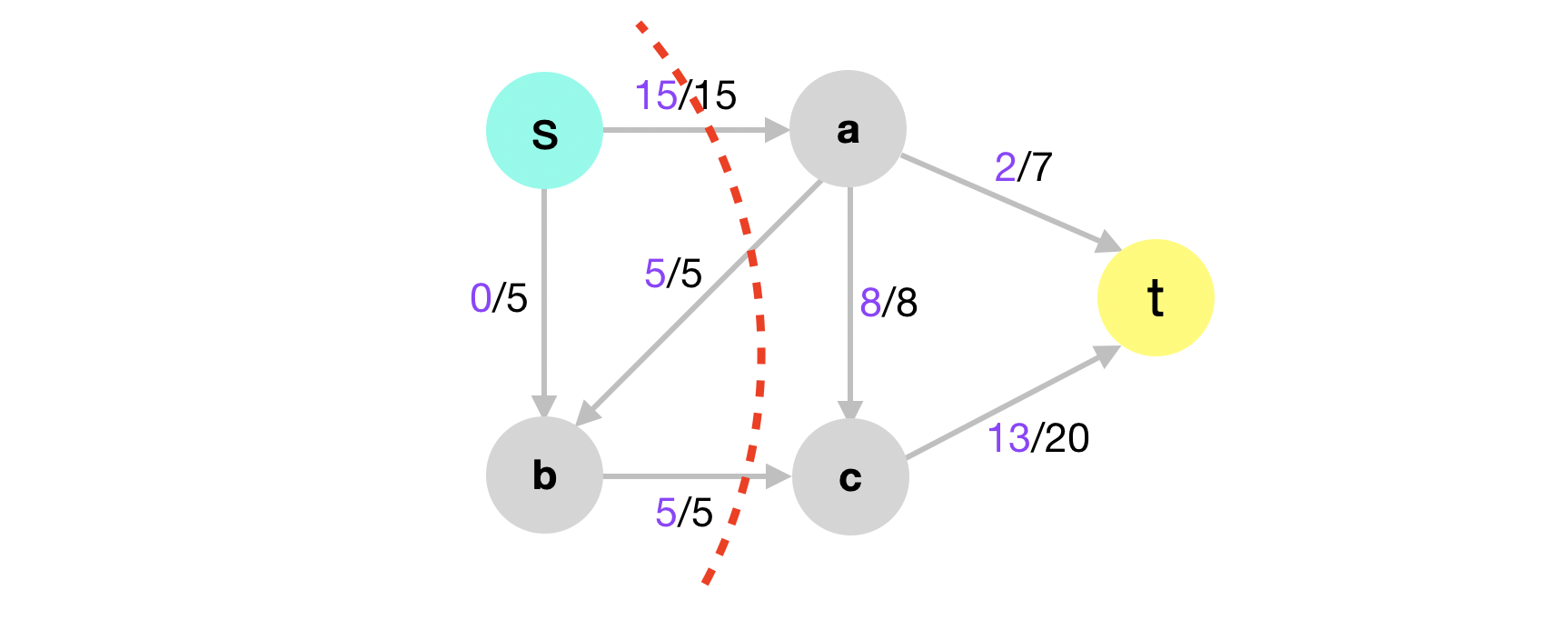

In the maximum-flow problem we are given a flow network \(G\) with a source vertex \(s\) and a sink vertex \(t\) and we are asked to find a flow of maximum value. In the above graph, the current flow is 15. Is this a maximum flow and how can we find a maximum flow in \(G\)?

A Greedy Idea

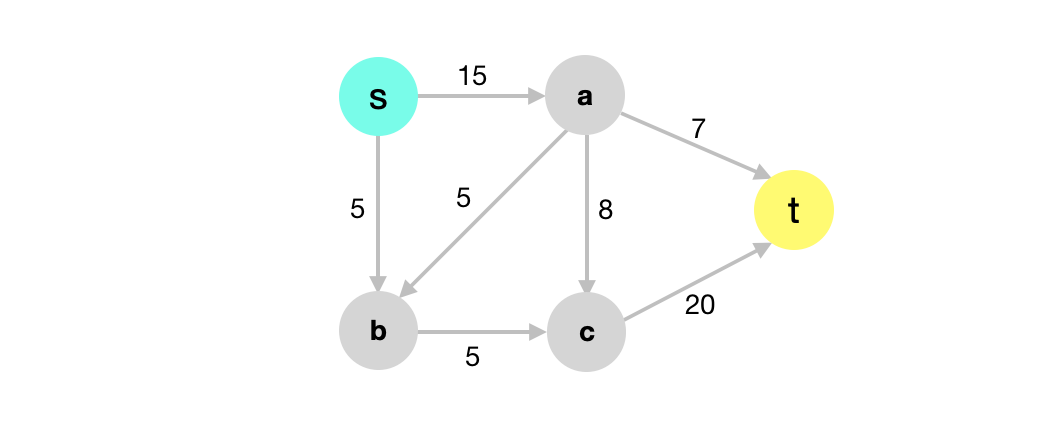

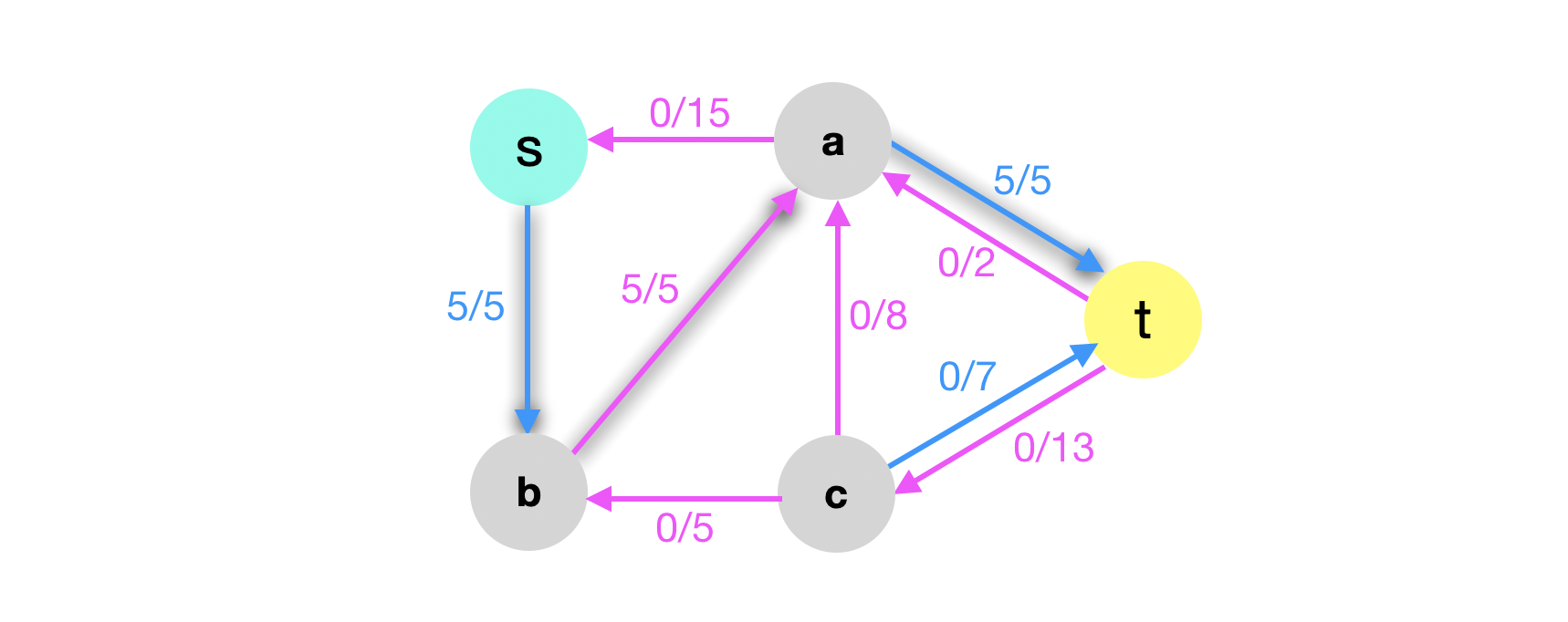

One greedy approach we might try is to push as much flow as possible starting from the source node. Suppose we have the below graph \(G\).

We’ll apply the strategy above by pushing as much as we can starting from \(s\).

We’ll apply the strategy above by pushing as much as we can starting from \(s\).

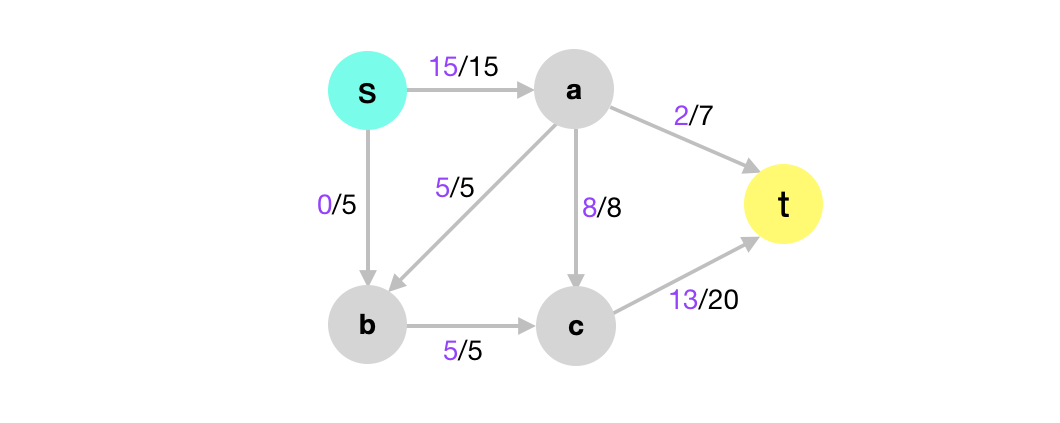

This flow is not optimal. In order to find the optimal flow we need to have a way to reduce the amount we’re pushing on \((a,b)\) and then push more instead on \((s,b)\) and \((a,t)\).

This flow is not optimal. In order to find the optimal flow we need to have a way to reduce the amount we’re pushing on \((a,b)\) and then push more instead on \((s,b)\) and \((a,t)\).

How do we implement the idea of removing flow from one part and adding it to another part in the graph? That’s what residual graphs are for! Residual graphs provide a way for us to increment or decrement flow in the original flow. Next, we’ll define formally what residual graphs are.

How do we implement the idea of removing flow from one part and adding it to another part in the graph? That’s what residual graphs are for! Residual graphs provide a way for us to increment or decrement flow in the original flow. Next, we’ll define formally what residual graphs are.

Residual Graphs

Let \(G=(V,E)\) be a flow network with source \(s\) and sink \(t\). Let \(f\) be a flow in \(G\). For any vertices \(u,v \in V\). The residual capacity \(c_f(u,v)\) by

This is the most confusing definition I’ve come across in CLRS. Algorithm Design however makes it super clear. The intution is that for every edge in \(G\), we want to create two edges.

- A forward edge to signify that we can still push more flow on this edge. So the capacity on the forward edge is \(c(u,v)-f(u,v)\).

- A backward edge to signify that we can decrease the flow on this edge by pushing back flow. So the capacity on the backward edge is naturally \(f(u,v)\).

In summary, the residual network of \(G\) induced by \(f\) is \(G_f=(V,E_f)\) where

Residual Graphs (Example)

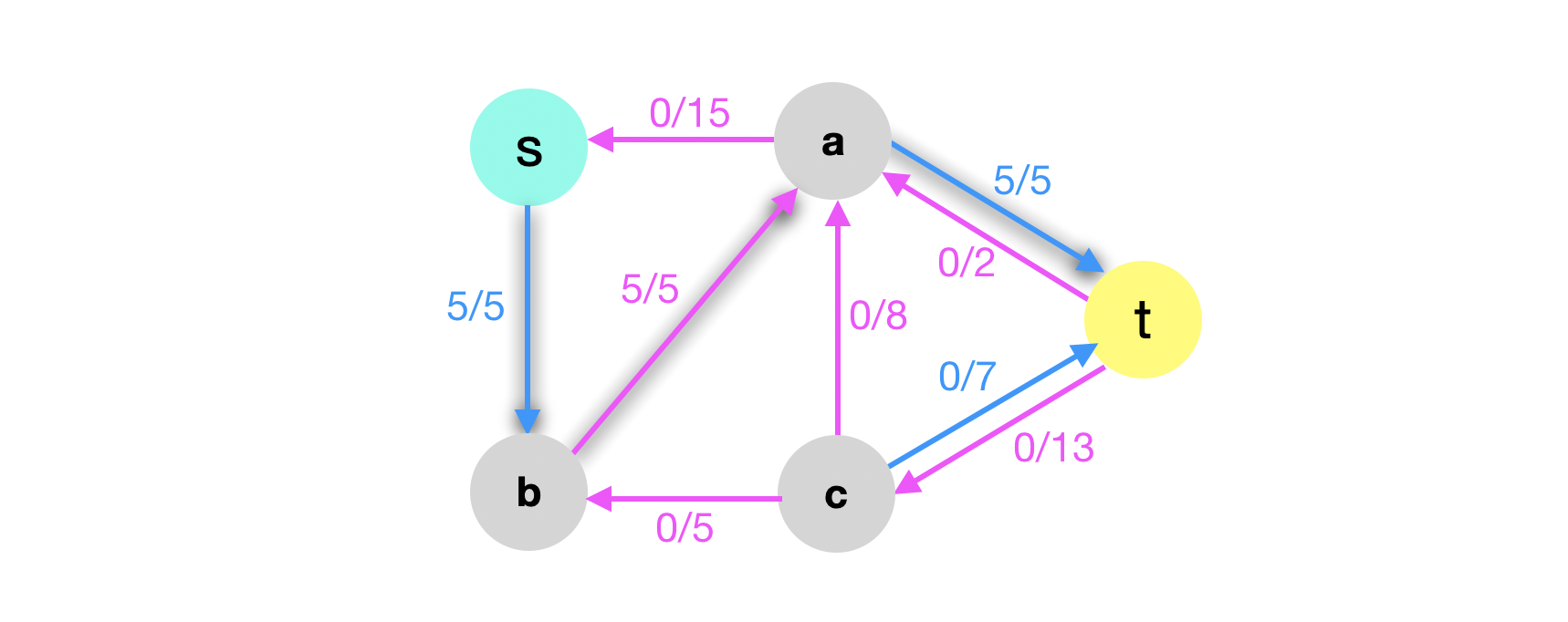

Let’s create a residual graph for the flow below:

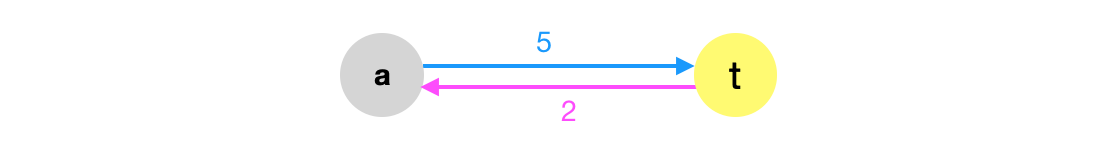

Let’s start with the edge \((a,t)\). We know that \(f(a,t) = 2\). Therefore we need to create two edges in \(G_f\). The first edge is a forward edge with capacity \(c_f(a,t) = c(a,t) - f(a,t) = 7 - 2 = 5\) which means that we can still possibly push 5 oranges on this path.

Let’s start with the edge \((a,t)\). We know that \(f(a,t) = 2\). Therefore we need to create two edges in \(G_f\). The first edge is a forward edge with capacity \(c_f(a,t) = c(a,t) - f(a,t) = 7 - 2 = 5\) which means that we can still possibly push 5 oranges on this path.

The other edge is a backward edge with a capacity \(c_f(t,a) = f(a,t) = 2\). This will be very useful of we want to decrement the flow on the edge \((a,t)\) in the original graph.

The other edge is a backward edge with a capacity \(c_f(t,a) = f(a,t) = 2\). This will be very useful of we want to decrement the flow on the edge \((a,t)\) in the original graph.

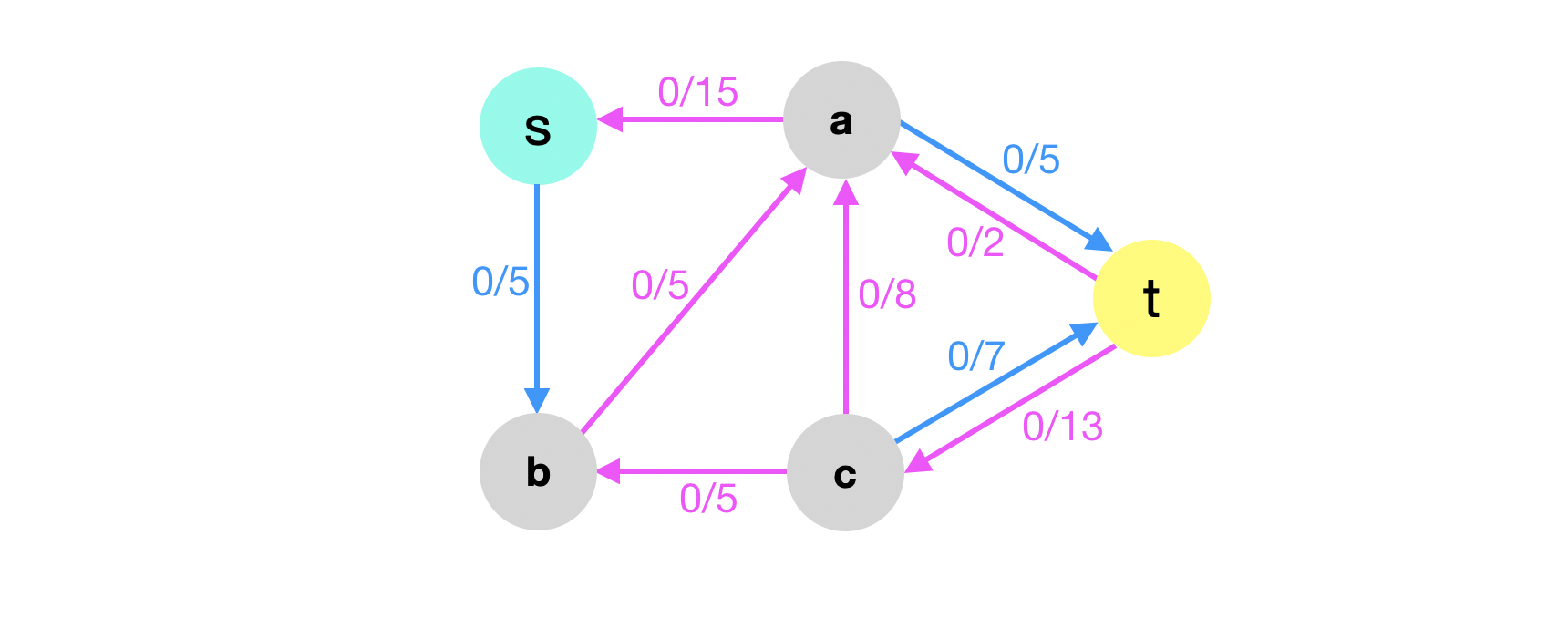

We repeat the process for all edges to generate the following graph. (Remember that we omit edges with capacity 0).

Flow in Residual Graphs

Suppose now we take \(G\) and \(G_f\) from the previous example and suppose we find a flow in \(G_f\) below

The claim is that this new flow in \(G_f\), call it \(f^{\prime}\) is actually a flow in \(G\). Moreover this new flow will result in an increased flow value in \(G\)! How is this even possible? To prove this we need to formalize this idea of adding the flow in the residual graph to \(G\) itself.

The claim is that this new flow in \(G_f\), call it \(f^{\prime}\) is actually a flow in \(G\). Moreover this new flow will result in an increased flow value in \(G\)! How is this even possible? To prove this we need to formalize this idea of adding the flow in the residual graph to \(G\) itself.

Formally, CLRS defines a new function, the augmentation of flow \(f\) by \(f^{\prime}\) to be a function from \(V \times V\) to \(R\) defined by

This looks absolutely scary but all it’s saying is that suppose we take the edge \((a,t)\) in \(G\). We are sending two units of flow on \((a,t)\). In the residual graph above, we’re sending 5 on the forward edge \((a,t)\) and 0 units on the backward edge \((t,a)\). Therefore,

And this is how we augment the flow on \((a,t)\) (\(f(a,t)\)) by the flow in \(G_f\) (\(f'(a,t) - f'(t,a)\)).

Augmenting Flow

Now we now that we have a formal definition of how we can augment the flow in \(G\) by the flow in \(G_f\). We want to prove that it is a valid flow in \(G\) and also that it is a better flow than the original flow.

Let’s first prove that it is a valid flow in \(G\). Given \(G\) and \(G_f\). Also given that \(f\) is a flow in \(G\) and that \(f^{\prime}\) is a flow in \(G_f\), we claim that \(|f \uparrow f'|\) is a flow in \(G\) and that it has value:

Proof:

Proof in CLRS consists of first verifying that \(f \uparrow f'\) obeys the capacity constraint and flow conversation in \(G\). After that, the proof computes the value of \(f \uparrow f'\). The proof proceeds as follows:

Let \(V_1\) include any vertex \(v\) such that \((s,v) \in E\) and let \(V_2\) include any vertex \(v\) such that \((v,s) \in E\). Since \(G\) doesn’t allow parallel edges by definition, then we know that \(V_1 \cap V_2 = \emptyset\). Therefore,

The proof proceeds with expanding each term and then finally concluding

This concludes that the new flow that resulted from combining both flows is a valid flow in \(G\)! But is this flow better that \(|f|\)? We want to prove that \(|f^{\prime}|>0\). To do so, we’ll define augmenting paths next.

Augmenting Paths

An augmenting path is a simple path \(p\) from \(s\) to \(t\) in the residual graph \(G_f\). Define its residual capacity or bottleneck (Algorithm Design) as follow:

So the bottleneck is just the minimum edge capacity on the path \(p\) in \(G_f\). To see this with an example, suppose we take the above residual graph from the previous example and find a simple path \(p\) in \(G_f\). Suppose we picked the following shaded path:

We can see that its bottleneck is 5 or \(c_f(p) = 5\). Next let’s define a new function \(f_p\) by

We can see that its bottleneck is 5 or \(c_f(p) = 5\). Next let’s define a new function \(f_p\) by

Based on this definition, we see that \(f_p\) is a flow in \(G_f\) with value

\(|f_p| = c_f(p)\) and \(c_f(p) > 0\). Therefore, \(|f \uparrow f_p| = |f| + |f_p| > |f|\).

So far we formalized the idea of augmenting flow in \(G\) by flow in \(G_f\). We proved that this flow is a valid flow. We also introduced the idea of augmenting paths used to create flow in the residual graph and therefore, additional flow in \(G\). We also proved that this new flow is also a larger flow than the original flow in \(G\). What’s left is to see how we can find augmenting paths and increase flow in action!

Augmenting Flow with New Flow in The Residual Graph

We can find an augmenting path by doing a breadth first search in \(G_f\). Once we have a path, how do we actually update \(G\) with the new updated flow? We illustrate below the process below:

void augment_flow(graph g, path p) {

// we first find the bottleneck or residual capacity of p in gf

b = bottleneck(p)

For each edge e=(u,v) in p {

if ((u,v) is in G) // e is a forward edge

// increase f(u,v) by b in g

f(u,v) = f(u,v) + cf(p)

else // (v,u) is is G // backward edge

// decrease f(v,u) by b in g

f(v,u) = f(v,u) - cf(p)

}

}To see an example, consider again the same shaded path we found in the previous example.

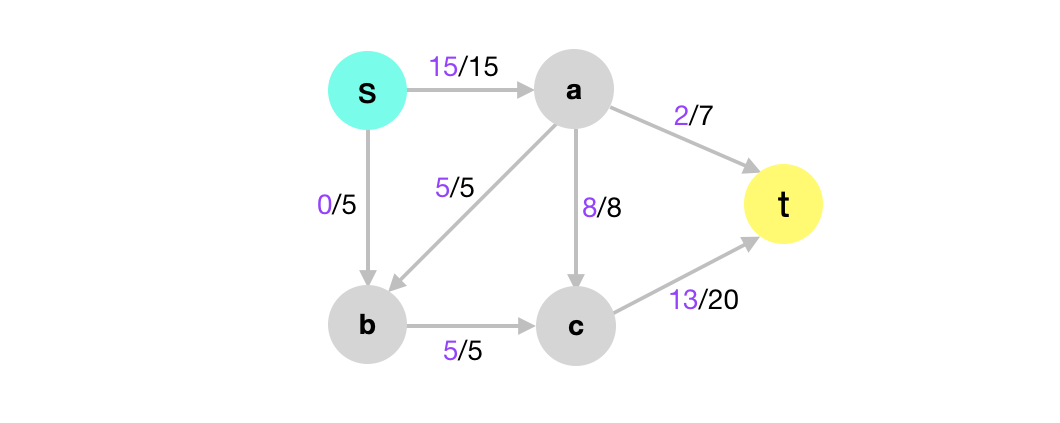

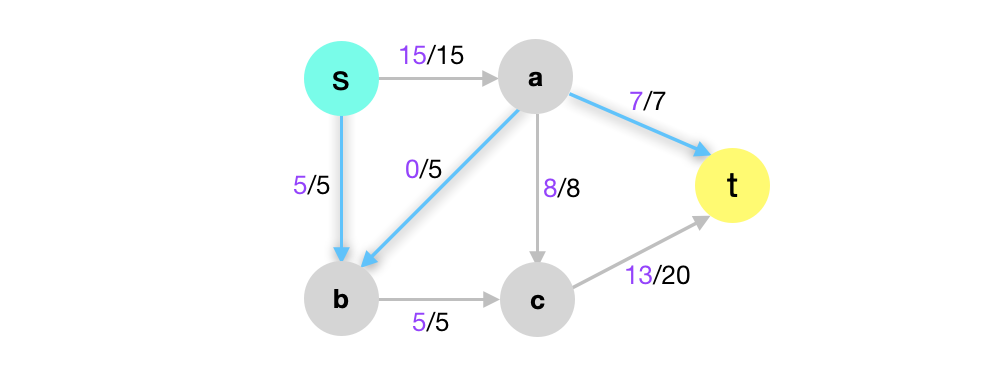

Let’s now add this flow back in \(G\). In this example, we see that \((s,b)\) is a forward edge (blue). Therefore, we increment \((s,b)\) in \(G\) by 5. Next, we see that \((b,a)\) is a backward edge and so we decrement \((a,b)\) in \(G\) by 5. Similarly \((a,t)\) is a forward edge and so we decrement it in \(G\) by 5. Let’s at \(G\) after augmenting \(p\).

Let’s now add this flow back in \(G\). In this example, we see that \((s,b)\) is a forward edge (blue). Therefore, we increment \((s,b)\) in \(G\) by 5. Next, we see that \((b,a)\) is a backward edge and so we decrement \((a,b)\) in \(G\) by 5. Similarly \((a,t)\) is a forward edge and so we decrement it in \(G\) by 5. Let’s at \(G\) after augmenting \(p\).

Now, let’s see what the new flow looks like in \(G\) after calling the above method. This flow has a higher value of \(20\) than the orignal flow!

The Ford-Fulkerson's Method

Now that we know how to add flow back to \(G\), we can describe the Ford-Fulkerson method. The Ford-Fulkerson method iteratively increases the value of the flow. We initially start with \(f(u,v)=0\) for all \((u,v) \in E\) and incrementally increase the flow value.

void Ford-Fulkerson(graph g) {

// initialize stuff

Initialize the residual graph gf.

For each edge (u,v), define f(u,v)=0.

// find an augemnting path and then augment flow in G

while (we can find a simple path p in gf from s to t) {

augment_flow(g,p)

}

}But do we ever terminate? and how do we know we have the optimal flow when we terminate?

Cuts in Flow Networks

In the Ford-Fulkerson’s method above, we see that we exit the while loop only when there are no augmenting paths available. So if the Ford-Fulkerson’s method does in fact generate a maximum flow, then it must be that a flow is maximum when we don’t any more augmenting paths. How do we prove this?

We need to explore yet another concept. A cut \((S,T)\) of a flow network \(G=(V,E)\) is a partition of \(V\) into \(S\) and \(T = V - S\) such that \(s \in S\) and \(t \in T\). Let \(f\) be a flow in \(G\).

The net flow \(f(S,T)\) across the cut \((S,T)\) is

The capacity of the cut \((S,T)\) is

Suppose we have the following flow with the following cut where \(S = \{s, b\}\) and \(T = \{a,c,t\}\). Wee see that the net flow is \(15+5-5=15\). The capacity of the cut is \(20\).

Lastly, define a minimum cut of a network to be a cut whose capacity is minimum over all cuts.

Lastly, define a minimum cut of a network to be a cut whose capacity is minimum over all cuts.

Cuts and Flow

We first want to establish that the flow we generate is a flow of maximum value. In order to do so, we need to prove smaller results that we will use in the main proof in the next section. Let’s prove the following:

Suppose \(f\) is a flow in \(G\) and let \((S,T)\) be any cut in \(G\) then the net flow across \((S,T)\) is \(f(S,T)=|f|\).

Proof

The proof isn’t too bad really. It starts with the definition of the value of the flow and adds the following: \(\sum_{v \in V}f(u,v)-\sum_{v \in V}f(v,u) = 0\) for all \(v \in V-\{s,t\}\) which is true because of the conservation law. It also uses the fact that \(S \cap T = \emptyset\) to further break the summations into smaller ones. Eventually we will arrive at \(f(S,T)\). (TODO: it’s long but maybe add it later)

The next thing CLRS proves is that the value of any flow \(f\) in a flow network \(G\) is bounded from above by the capacity of any cut of \(G\).

Proof

This one is extremely short because it uses what we proved above.

The Max-Flow Min-Cut Theorem

FINALLY, we are ready to prove the max-flow min-cut theorem below:

If \(f\) is a flow in \(G=(V,E)\) with source \(s\) and sink \(t\) then the following conditions are equivalent:

(1) \(f\) is a maximum flow in \(G\).

(2) The residual network \(G_f\) contains no augmenting paths.

(3) \(|f|=c(S,T)\) for some cut \((S,T)\) of \(G\).

Proof

We have several directions:

\(1 \rightarrow 2\):

Let the maximum flow in \(G\) be \(f\) and for the sake of contradiction, suppose that there exists some augmenting path \(p\) in \(G_f\). Let \(f_p\) be the flow in \(G_f\) as we defined previously. We proved earlier that \(|f \uparrow f_p| = |f| + |f_p| > |f|\). Therefore, the new flow founded by augmenting \(f\) by \(f_p\) is strictly greater than \(|f|\). This is a contradiction since we assumed \(|f|\) is of maximum value.

\(2 \rightarrow 3\):

This part is sneaky. Suppose we don’t have augmenting paths in \(G_f\). This means that we don’t have a path from \(s\) to \(t\) in \(G_f\). Based on this, define \(S = \{u \in V:\) there exists a path from \(s\) to \(v\) \(\}\) and let \(T = V - S\). We know \(s \in S\) and \(t \not\in S\). Therefore, the partition \((S,T)\) is a cut.

Now for any vertices \(u \in S\) and \(v \in T\). There are two cases:

Case 1: If \((u,v) \in E\), then we must have \(f(u,v) = c(u,v)\). This is because if \(f(u,v) \leq c(u,v)\) then this means that \((u,v) \in E_f\) (Remember “capacity-flow > 0” in \(G\) creates forward edges in \(G_f\)). Therefore, \(v\) must be in \(S\) and this can’t be by assumption.

Case 2: If \((v,u) \in E\), then we must have \(f(v,u) = 0\). This is because if \(f(v,u) > 0\) then we must have \((u,v) \in E_f\) (Remember flow in \(G\) creates backward edges in \(G_f\)). Therefore, \(v\) must be in \(S\) and this can’t be by assumption.

Case 3: If \((v,u) \not\in E\) and \((u,v) \not\in E\) then \(f(u,v) = f(v,u) = 0\).

Therefore, combing everything and utilizing the fact that \(|f| = f(S,T)\):

\(3 \rightarrow 1\):

We established previously that \(|f| \leq c(S,T)\) for any cut \((S,T)\) in \(G\). Therefore, if \(|f| = c(S,T)\) for some cut \((S,T)\) in \(G\) then it must be that \(f\) is a flow of maximum value.

Does Ford-Fulkerson Terminate?

An essential component in the proof that Ford-Fulkerson terminates is the assumption that the capacities in \(G\) are integers otherwise we might not converge to the optimal flow in \(G\). So given that we integer capacities, we need to prove three components:

- The flow values and the capacities in \(G_f\) remain integers in every iteration.

- In each iteration of Ford-Fulkerson, the flow value increases.

- There is an upper bound on the maximum flow value.

Given a flow network \(G\) and its residual network \(G_f\). For (1) given an augmenting path, we know that the bottleneck value or the residual capacity is just the minimum value of all the edge capacities on \(p\) in \(G_f\). Therefore, the new flow must have an integer value.

For (2), we defined formally the augmentation of \(f\) by \(f^{\prime}\) and we proved that for any augmenting path and flow \(f_p\), we must have \(|f| + |f_p| > |f|\).

For (3), we can simply use the upper bound from the definition of the value of flow itself. Recall that

We can therefore, let \(C = \sum_{v \in V}f(s,v)\) and so \(|f| \leq C\). Along with (1) and (2), we can conclude that Ford-Fulkerson must terminate in at most \(C\) iterations.

Running Time

We know that \(G\) is connected and so finding an augmenting path using a depth first search or a breadth first search will run in \(O(E + V) = O(E)\) time. Updating the augmenting path in each iteration costs \(O(E)\) time. How many times do we loop? Given that the capacities are integers and depending on the maximum value of flow, \(|f^*|\), the total running time is \(O(E \ |f^*|)\).

Edmonds-Karp

One way to improve Ford-Fulkerson is by smartly choosing the augmenting path in each iteration. Edmonds-Karp chooses the shortest path from \(s\) to \(t\) where each edge has unit weight. Edmonds-Karp runs in \(O(VE^2)\) time. Why?

TODO

References

These are my study notes covering chapter 26 in CLRS and chapter 7 in Algorithm Design.