Given an array \(A\), the Cartersian tree, \(C(A)\), is defined as follows:

Given an array \(A\), the Cartersian tree, \(C(A)\), is defined as follows:

- If \(A = \emptyset\), then \(C(A) = \emptyset\), the empty tree.

- If \(A \neq \emptyset\), then let \(min\) be the minimum element in \(A\) and let \(i\) be the index of \(min\). Fix the root of the Cartesian tree to be \(min\) and let \(\text{left}(A) = \{x_j \in A \ \ | \ \ j < i\}\) be the points on the left of \(i\) and \(\text{right}(A) = \{x_j \in A \ \ | \ \ j > i\}\) be the points on the right of \(i\). Let the root’s left child be the cartesian tree of the left points, \(C(\text{left}(A))\). and the root’s right child be the cartesian tree of the right points, \(C(\text{right}(A))\).

Notice that the Cartersian trees obey the min-heap property and also an in-order traversal of the Cartersian tree, results in the original array.

Naive Algorithm

The following basic algorithm is very similar to QuickSort. The runtime depends on how the minimum evenly splits the array \(A\). The expected-case runtime would be \(O(n\log(n))\) and the worst-case runtime would be \(O(n^2)\).

cartesian_tree(A) {

if (a is empty) { return null }

left, min, right = split A around the minimum element in O(n) time.

create a new node for min

new_node.left = cartersian_tree(left)

new_node.right = cartesian_tree(right)

return new_node

}

Example

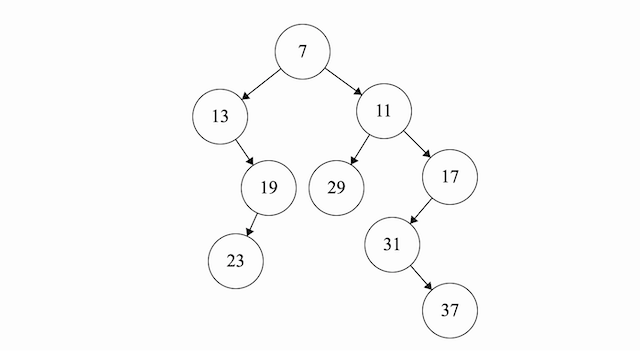

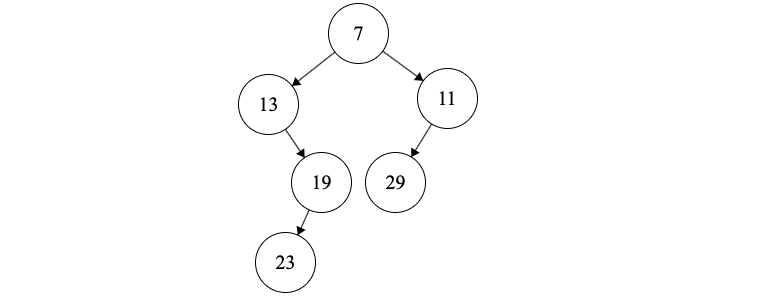

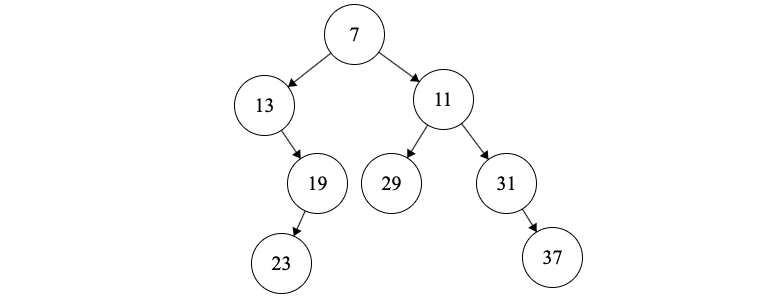

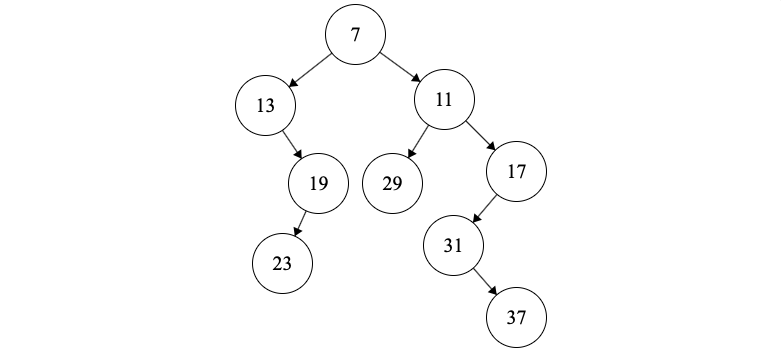

Given the above array, we construct the following cartersian tree:

- 7 is the minimum element and so everything before 7 is the left child of 7 and everything after 7 is the right child of 7.

- Next, we recursively create the left and right cartersian trees. We pick 13 as the minimum on the left subarray [13, 23, 19]. and we pick 11 as the minimum in the right subarray [29, 11, 31, 37, 17]. We repeat the process until we run out of elements.

O(n) Algorithm

The previous algorithm is not fast enough. Given an array \(A\) of length \(n\). A key insight is that given the cartesian tree for \(A[1...i]\), the cartesian tree for \(A[1...i+1]\) can be constructed by observing that the element \(A[i+1]\) must be right most node in the right most path in the tree because we know that an inorder traversal of the tree must give back the original array \(A\). Basically \(A[i+1]\) should be the last visited node in the in-order traversal of \(A[1...i+1]\).

Therefore, maintain a stack of the right most path in the tree. While the stack is not empty, we repeatedly check if the top element is greater than our current element \(A[i]\). If \(A[i]\) has a higher value, we stop. Now we do two things:

(1) Let the top element in the stack be \(t\). Since \(t < A[i]\), then \(t\) must be closer to the root than \(A[i]\) to maintain the min-heap property. Also in an in-order traversal, \(A[i]\) must come after \(t\). Therefore, \(A[i]\) should be the right tree of \(t\).

(2) Let the the last element popped be \(q\). Since \(q > A[i]\), then \(q\) must be lower than \(A[i]\) in the tree. It must also come before \(A[i]\) in an in-order traversal and therefore, it should be the left tree of \(A[i]\).

(3) The last thin

A = [...]

// maintain a stack s

s = []

for (i = 0 .. n-1) {

new_node = create a new node for A[i]

last_popped = null

while (!s.empty() and s.top() > A[i]) {

last_popped = s.top()

s.pop()

}

// (1) the last popped node is the left tree of the new node

new_node.left = last_popped

// (2) the top value in the stack will set its right child to the new node

if (!s.empty()) {

s.top().right = new_node

}

// (3) push the node on the stack

s.push(new_node);

}

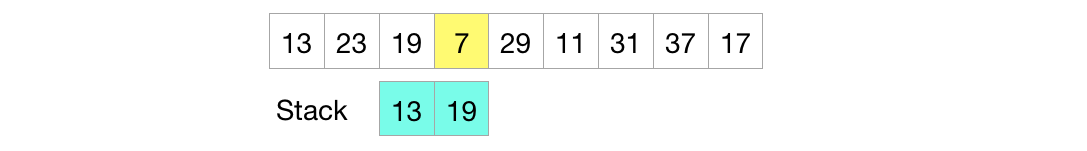

Example

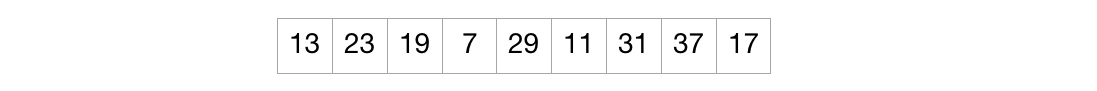

Assume that we are creating a cartesian tree for the array above.

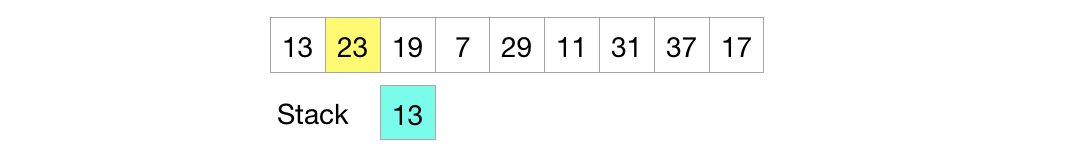

(1) We first look at \(A[0]=13\).

Since the stack is empty and last_popped is also null, then all we do is create a node for \(13\) and push it on the stack.

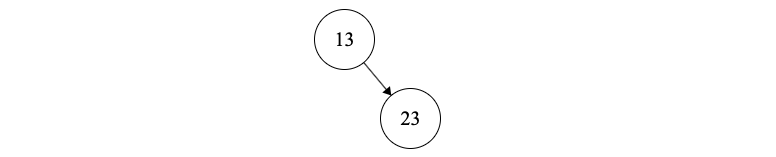

(2) Next we insert \(A[1]=23\). Here, we don’t pop anything form the stack. we assign the node \(A[i]\) to be the right tree of the top element in the stack.

This results in the following tree

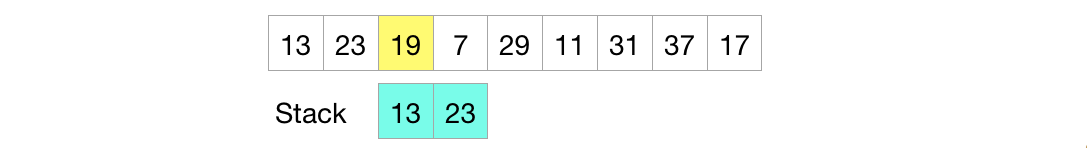

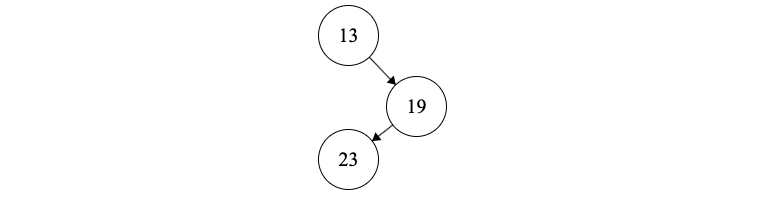

(3) Next we insert \(A[1]=19\). Here, we pop 23. 19’s left tree is 23. We also assign 19 to be the right tree of the top element in the stack, 13. We then push 19 on the stack

This results in the following tree

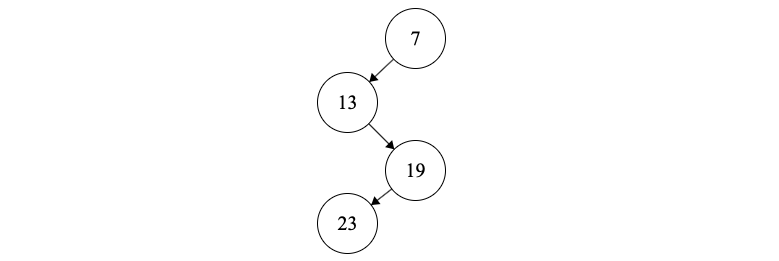

(4) Next we insert \(A[1]=7\). We pop 19 and then 13. The last popped node is 13. 7’s left tree is 13. The stack is empty so we do nothing else and push 7 on the stack.

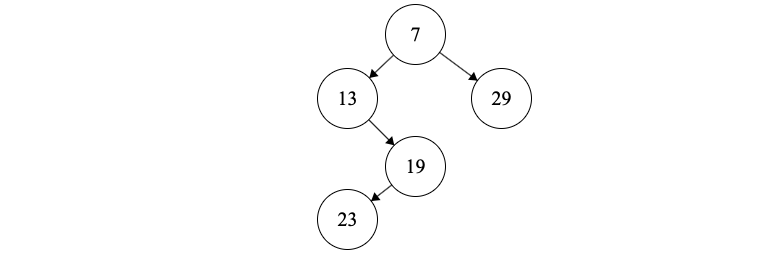

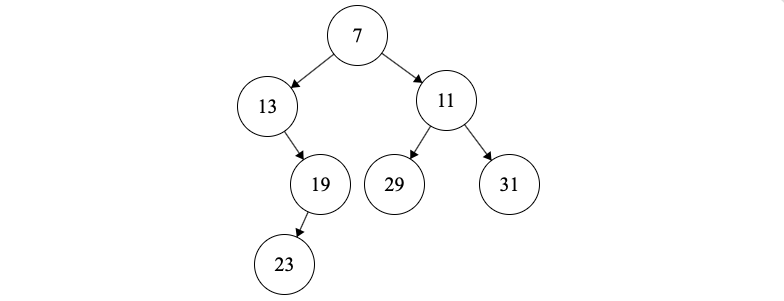

This results in the following tree

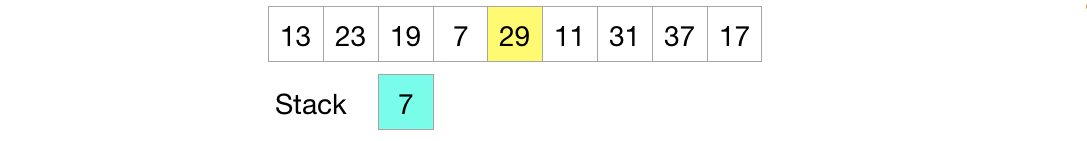

(4) Next we insert \(A[1]=29\). We don’t pop anything. 29 will be the right tree of 7 and we push 29 on the stack.

This results in the following tree

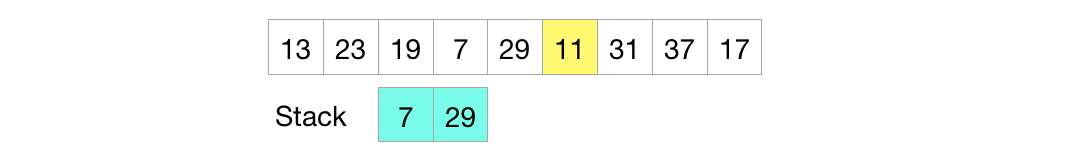

(5) Next we insert \(A[1]=11\). We pop 29. 11’s left tree will be 29. 11 will be the right tree of 7 and we push 11 on the stack.

This results in the following tree

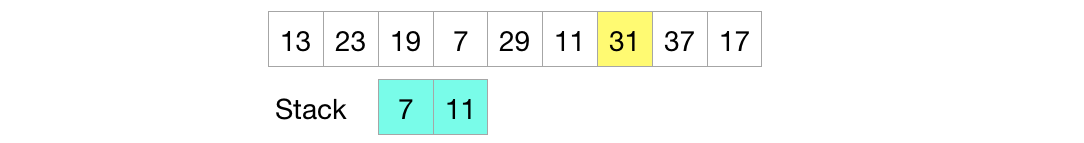

(6) Next we insert \(A[1]=31\). We don’t pop anything. 31 will be the right tree of 11 and we push 31 on the stack.

This results in the following tree

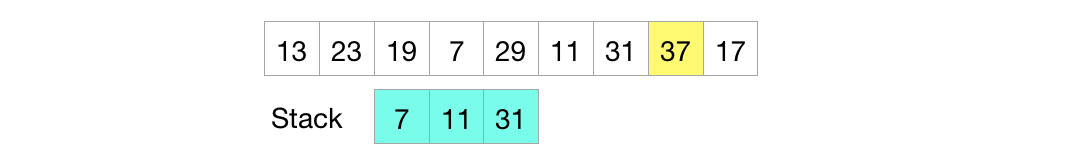

(7) Next we insert \(A[1]=37\). We don’t pop anything. 37 will be the right tree of 31 and we push 37 on the stack.

This results in the following tree

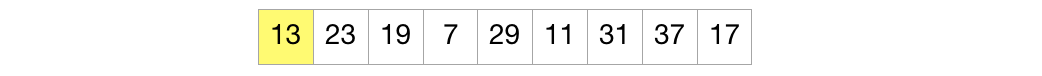

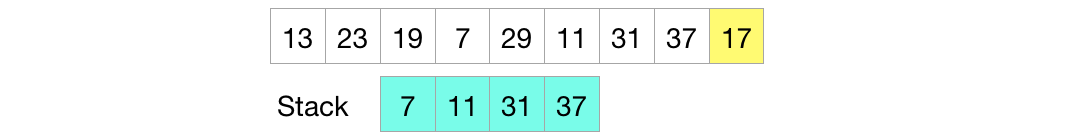

(8) Next we insert \(A[1]=17\). We pop 37 and 31. 31 will be the right tree of 17. 11’s left tree will be 17. We push 17 on the stack.

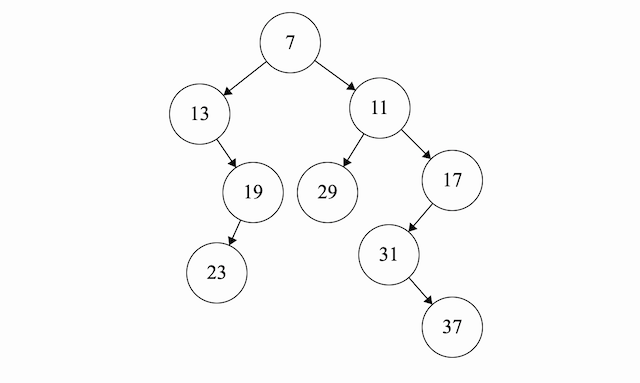

This results in the following tree

Proof of Correctness

???

Implementation:

https://github.com/strncat/algorithms-and-data-structures/blob/master/rmq/catersian-trees.cpp

References

- Jean Vuillemin. 1980. A unifying look at data structures. Commun. ACM 23, 4 (April 1980), 229-239. DOI=http://dx.doi.org.stanford.idm.oclc.org/10.1145/358841.358852

- CS166 Lecture Notes http://web.stanford.edu/class/cs166/lectures/01/Slides01.pdf