So now that we know that every polygon \(p\) has a triangulation, how are we going to triangulate \(p\)? The key to proving that triangulation exists was finding a diagonal. Similarly, the first step in triangulation is to find an internal diagonal. Given a diagonal candidate we need to verify two conditions:

- \(\overline{ab}\)'s intersection with the boundary of \(P\) is exactly its end points \(a\) and \(b\) and nothing else.

- \(\overline{ab}\) is an an internal diagonal.

How can we verify the above conditions? In this post, we’ll develop procedures to verify these two conditions.

Condition 1: Intersection of the diagonal \(d\) with the boundary of \(p\)

So given a diagonal candidate \(d\) with end points \(a\) and \(b\), how do we go about testing its intersection with the boundary of \(p\). The boundary consists of the edges of the polygon. The diagonal is incident to at most 4 of these edges. If we keep this case separately and focus on the rest of edges, then we simply want to know if this candidate doesn’t intersect ANY of these edges besides the special 4. In other words, for all other edges that are not incident to \(a\) or \(b\), their intersection with \(d=ab\) is empty.

Segment Intersection

Since we only care about the existence of an intersection rather than the intersection point itself, then we can go back to what we studied before about the orientation of three ordered points (see Orientation of Three Points post and also Segment Intersection (CLRS)). Suppose we’re given three ordered points \(p, q, r\), then the expression \((q_x-p_x)(r_y-p_y) - (r_x-p_x)(q_y-p_y)\) is

- Greater than zero when the slope of \(pq\) is smaller than the slope of \(pr\) and so the ordered points \(p, q\) and \(r\) are in anti-clockwise orientation and \(r\) is on the left of the line \(pq\)

- Equal to zero if they're collinear

- Less than zero when the slope of \(pq\) is greater than the slop of \(pr\) and so the ordered points \(p, q\) and \(r\) in a counter clockwise orientation and \(r\) is on the left of the line \(pq\)

We can write a little helper to compute this

// determines if r is on the left of the line pq

int direction(p, q, r) {

int product = (q_x-p_x)(r_y-p_y) - (r_x-p_x)(q_y-p_y);

if (product > 0) {

return 1; // anti-clockwise

} else if (product < 0) {

return -1; // clockwise

}

return 0; // collinear

}

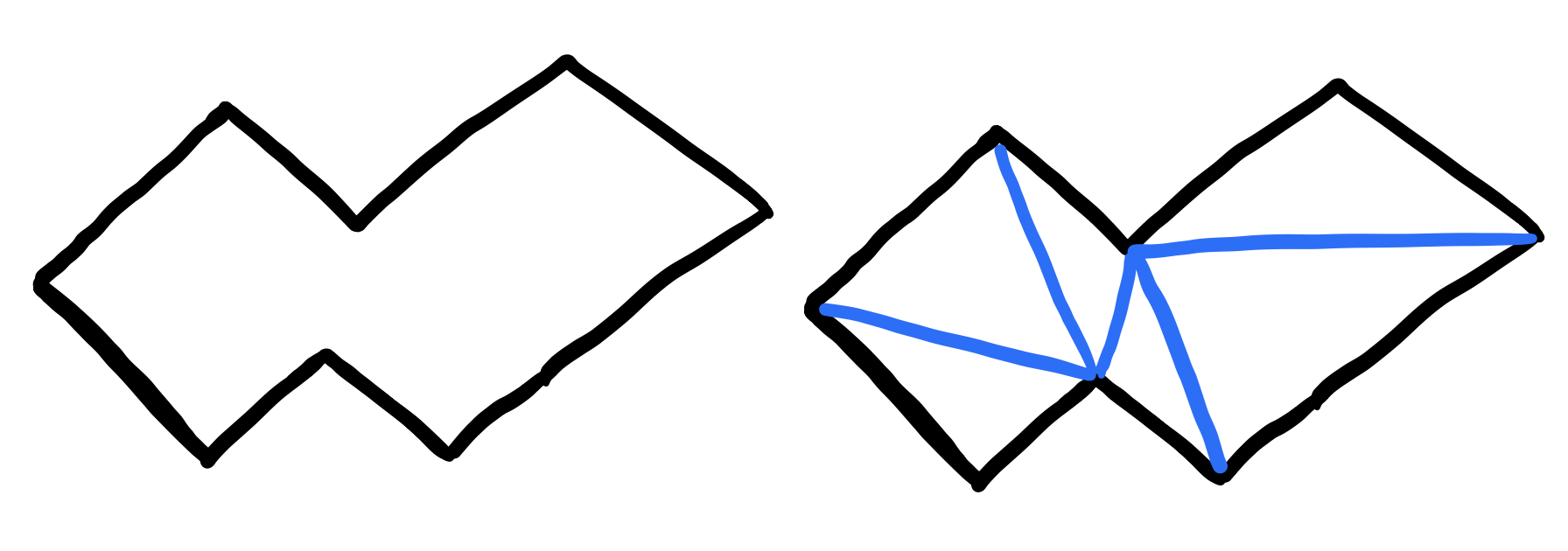

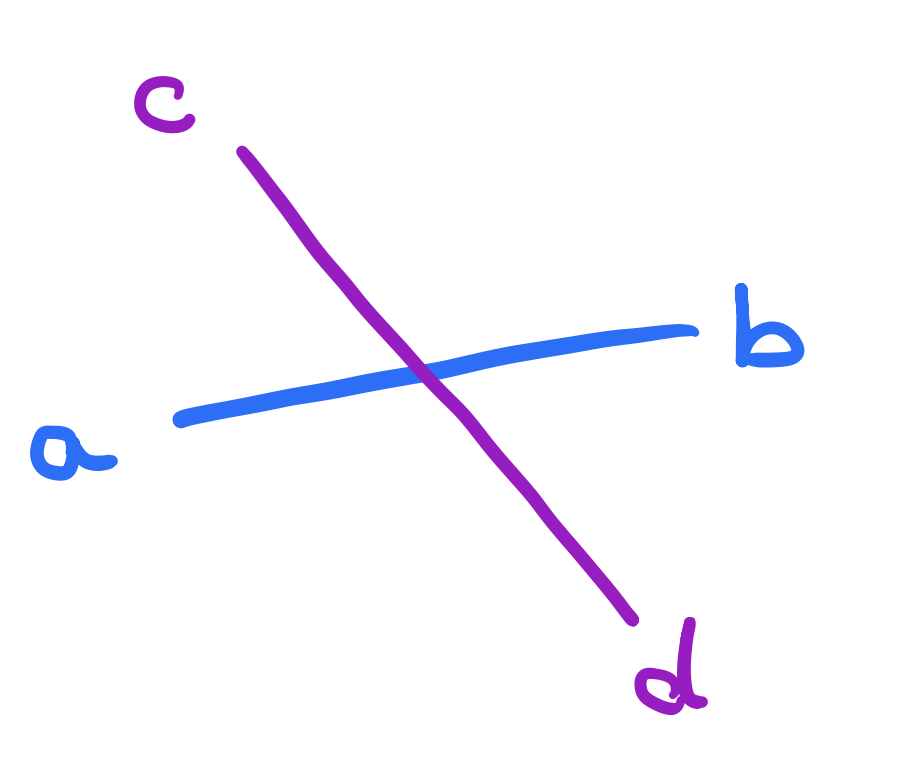

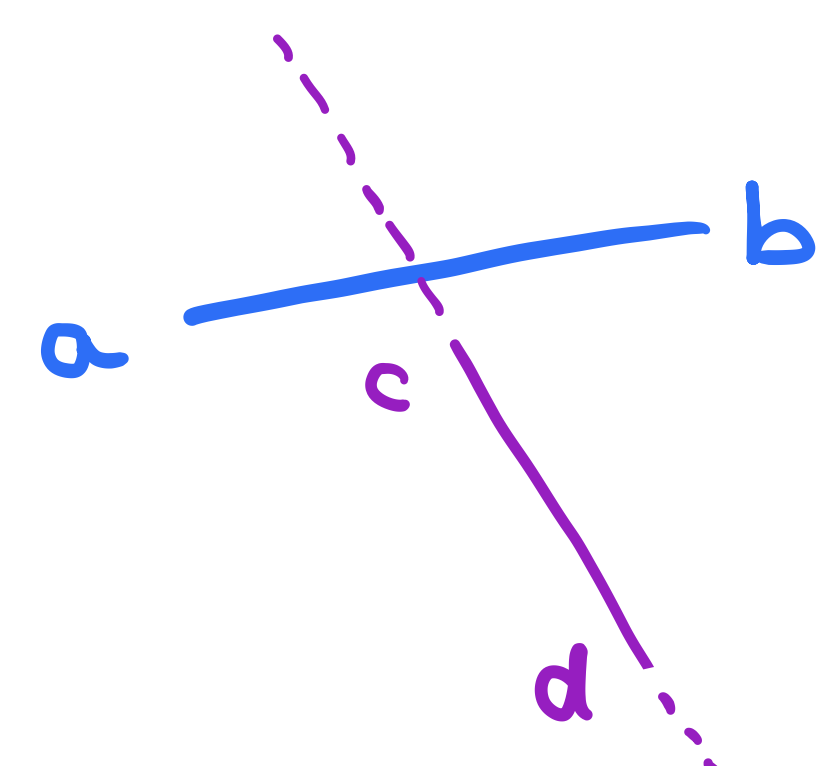

How do we use this test to determine if \(\overline{ab}\) and \(\overline{cd}\) intersect? We can use it to test if the points \(a\) and \(b\) are on opposite sides of the line that goes through \(\over{cd}\) above. But is this enough? No! Consider the following figure.

\(a\) and the \(b\) are in fact on opposite sides of the line that goes through \(c\) and \(d\) but the segment from \(a\) to \(b\) doesn’t intersect the segment that goes through \(c\) and \(d\)! To fix this, we also need to ask whether the points \(c\) and \(d\) are on opposite sides of the line that goes through \(\overline{ab}\) and the answer is clearly not! \(c\) and \(d\) are on the same side. This is great but there is one more condition to consider. Consider the following:

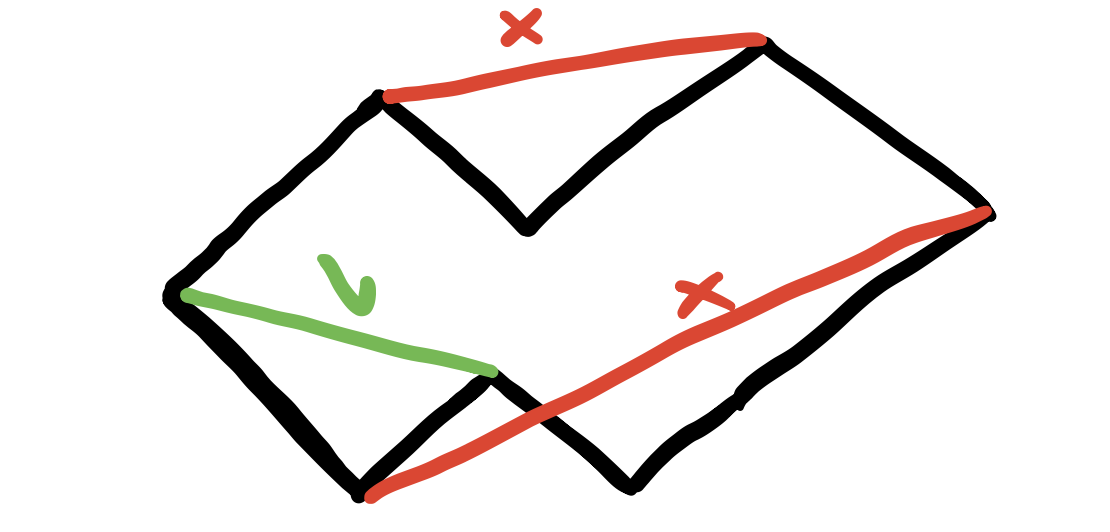

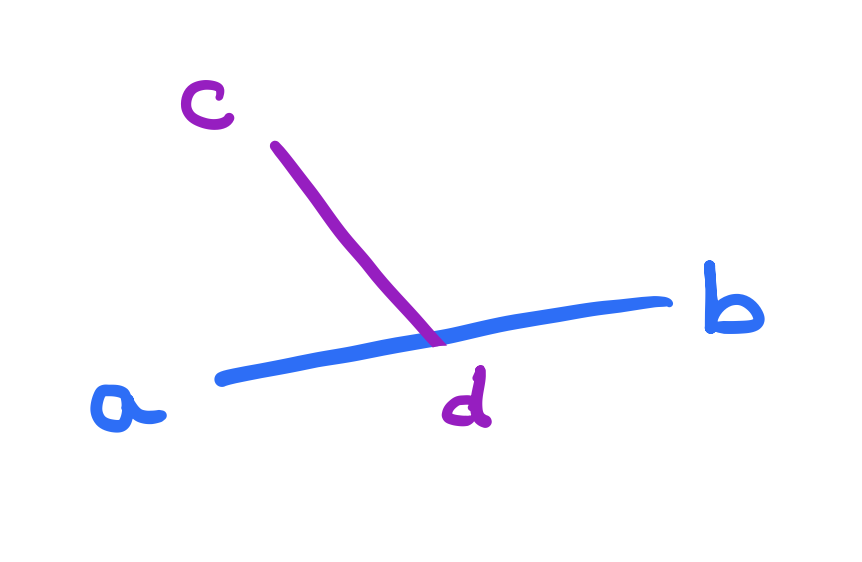

Here, the points \(a\), \(d\) and \(b\) are collinear. So \(c\) and \(d\) are not exactly on opposite sides but they still intersect! So what do we do here? In the book that I’ve been studying “Computational Geometry in C”, the intersection function is split into two to handle the case of improper intersection (when the points are collinear) and the case of proper intersection (when the points are not collinear). I personally found the CLRS way of computing the intersection all at once was easier to understand (likely due to the fact that I studied it first!). In CLRS, we test for proper intersection and in the same function later on, we handle the case when the points are collinear to additionally verify that they indeed intersect.

bool interesect(a, b, c, d) {

int d1 = direction(a, b, c); // which side is c on?

int d2 = direction(a, b, d); // same for d

int d3 = direction(c, d, a);

int d4 = direction(c, d, b);

// proper intersection

if ((d1 < 0 && d2 > 0) || (d2 < 0 && d1 > 0) ||

(d3 < 0 && d4 > 0) || (d4 < 0 && d3 > 0)) {

return true;

}

// improper intersection

// check if c sits between the end two points

if (d1 == 0 && between_line_segment(a, b, c)) return true;

// check if d sits between the end two points

if (d2 == 0 && between_line_segment(a, b, d)) return true;

// check if a sits between the end two points

if (d3 == 0 && between_line_segment(c, d, a)) return true;

// check if b sits between the end two points

if (d4 == 0 && between_line_segment(c, d, b)) return true;

}So now we have a function that will test if a given candidate \(d\) intersects the boundary of \(P\) except for the special edges that are incident to \(d\) itself.

bool diagonalie(tVertex *a, tVertex *b) {

tVertex *c, *c1;

/* For each edge (c,c1) of P */

c = vertices;

do {

c1 = c->next;

/* Skip edges incident to a or b */

if ((c != a) && (c1 != a) && (c != b) && (c1 != b)

&& intersect(a->v, b->v, c->v, c1->v)) {

return false;

}

c = c->next;

} while (c != vertices);

return true;

}Next we will study condition 2 which will handle both testing to see if \(d\) is internal and testing the special edges that we didn’t consider this round.

Condition 2: \(d\) is an internal diagonal (and more)

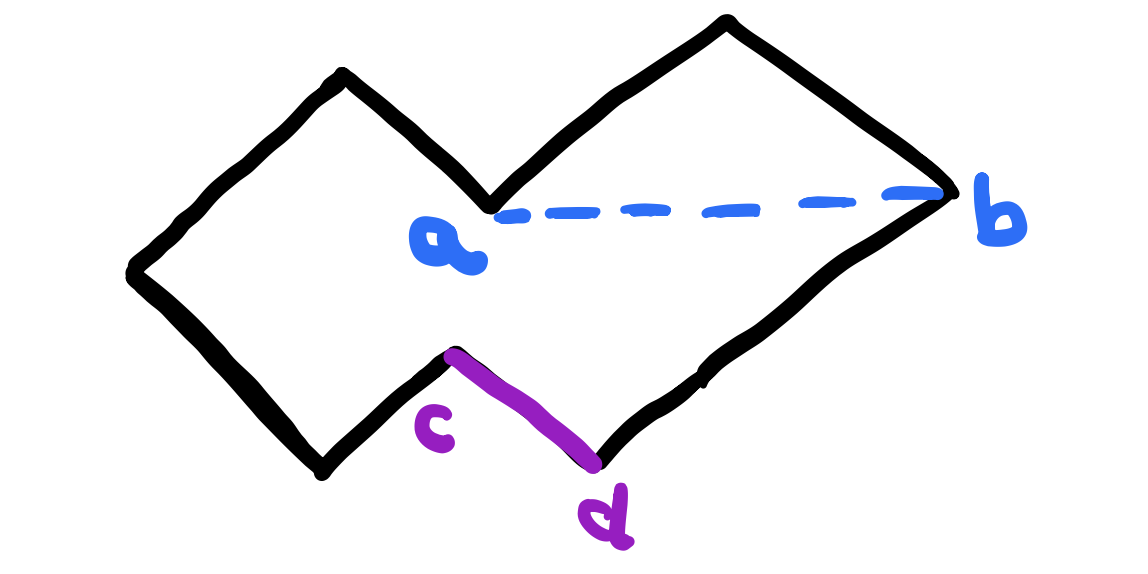

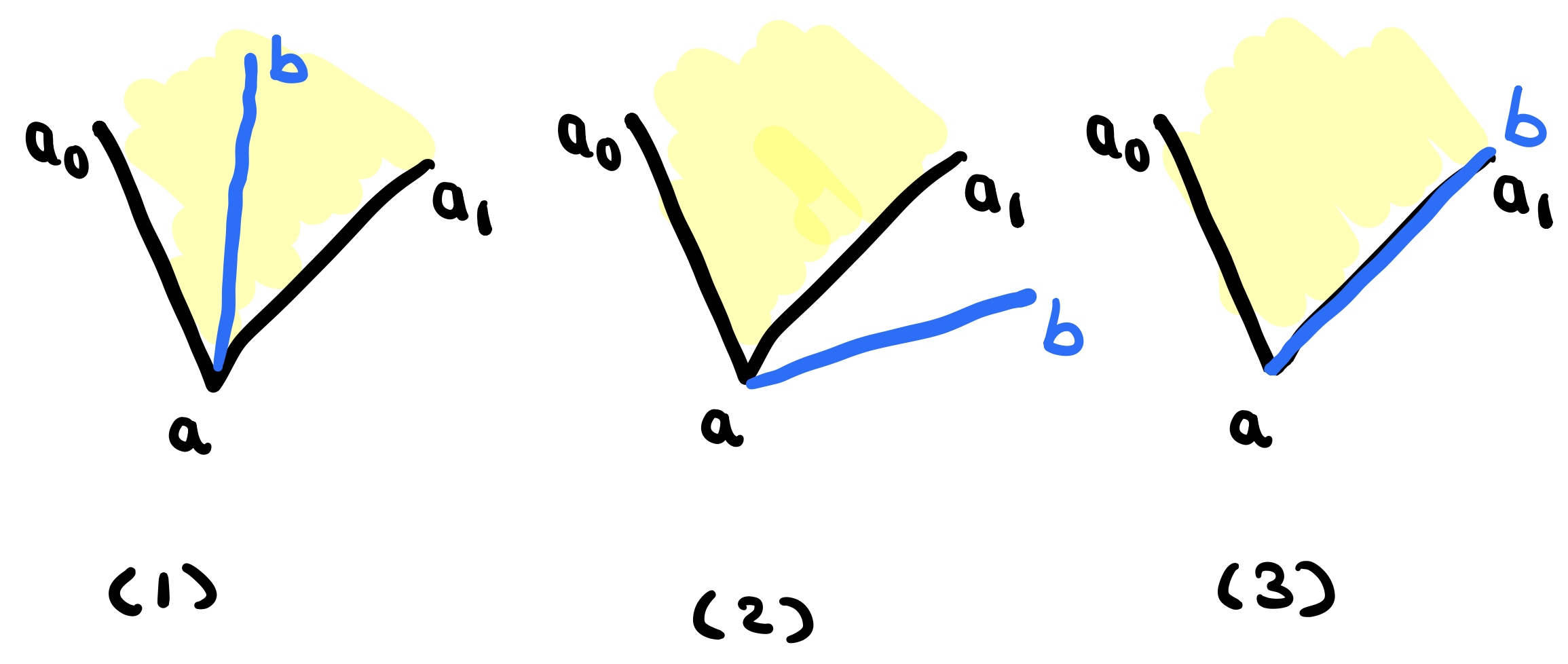

Suppose that \(d\) indeed doesn’t intersect the boundary (minus the special edges). \(d\) has two vertices \(a\) and \(b\). We will perform the following test on both vertices but just for demonstration, let’s choose vertex \(a\). Suppose that vertex \(a\) is a convex vertex (this can be determined by checking if \(a\) is on the (left or on) of the line that goes through \(\overline{aa_0}\)). Let’s consider the following cases:

- In figure (1), \(a_0\) is the left of the line that goes through \(d\) and \(a_1\) is on the right of the line that goes through \(d\) so we satisfy both conditions and \(d\) is indeed internal

- In figure (2), both \(a_0\) and \(a_1\) are on the left of the line that goes through \(\overline{ab}\)

- In figure (3), \(a, a_1\) and \(b\) are all collinear. So testing whether \(a_1\) is on the right of \(d\) will fail immediately.

So it seems like we can conclude that \(d\) is internal when:

- \(a_0\) is on the left of the line that goes through \(d=\overline{ab}\).

- \(a_1\) is on the right of the line that goes through \(d=\overline{ab}\).

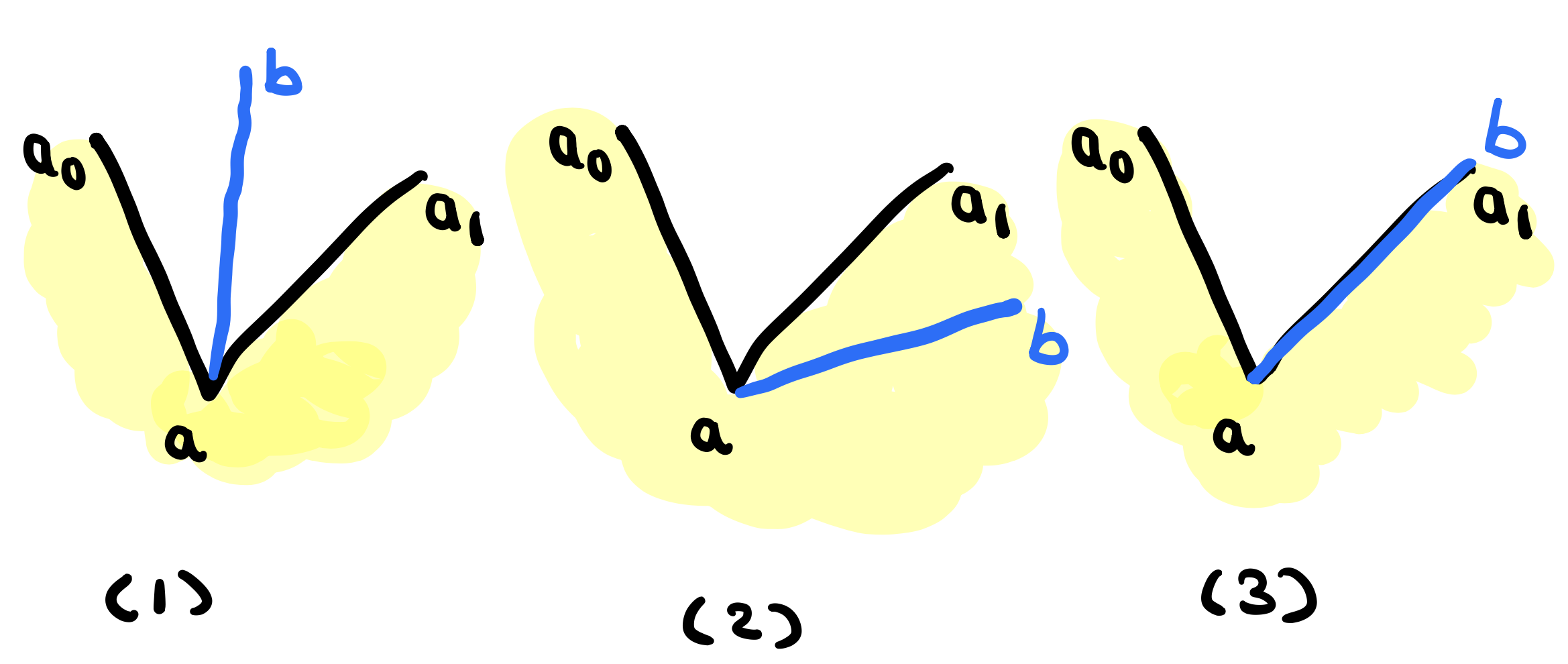

(TODO: Actual proof?). Now let’s look at the concave vertex case and see some cases:

- In figure (1), \(a_0\) is the right of the line that goes through \(d\) and \(a_1\) is on the left of the line that goes through \(d\) and \(d\) is not internal.

- In figure (2), both \(a_0\) and \(a_1\) are on the left of the line that goes through \(\overline{ab}\). In fact we can draw \(ab\) to the right of the two points or between the two points

- In figure (3), \(a, a_1\) and \(b\) are all collinear. \(d\) is not internal.

So the diagonal can really be anywhere. But the clever observation here is that if you compare the concave vertex figures to the convex vertex figures, you’ll see that the only difference is the shaded region is now on the opposite side. In fact, when I drew the second set of cases, I just copied the first 3 figures and changed the shaded areas to be the opposite. This means that we can take the same conditions above for the convex vertex and just conclude that if these conditions are NOT present, then we have an internal diagonal. There is one tiny detail though! instead of left and right, we need to check for (left and on) and (right and on) since we don’t want the case when the points are collinear.

bool in_cone(tVertex *a, tVertex *b) {

tVertex *a0, *a1; /* a0,a,a1 are consecutive vertices. */

a1 = a->next;

a0 = a->prev;

/* If a is a convex vertex */

/* right(a->v, b->v, a1->v) is the same as left(b->v, a->v, a1->v) */

if (left_on(a->v, a1->v, a0->v)) {

return left(a->v, b->v, a0->v) && left(b->v, a->v, a1->v);

}

/* else a is reflex: */

return !(left_on( a->v, b->v, a1->v) && left_on(b->v, a->v, a0->v));

}And finally we can write a function to test if a candidate segment is an internal diagonal below,

bool is_diagonal(tVertex *a, tVertex *b) {

return in_cone(a, b) && in_cone(b, a) && diagonalie(a, b);

}