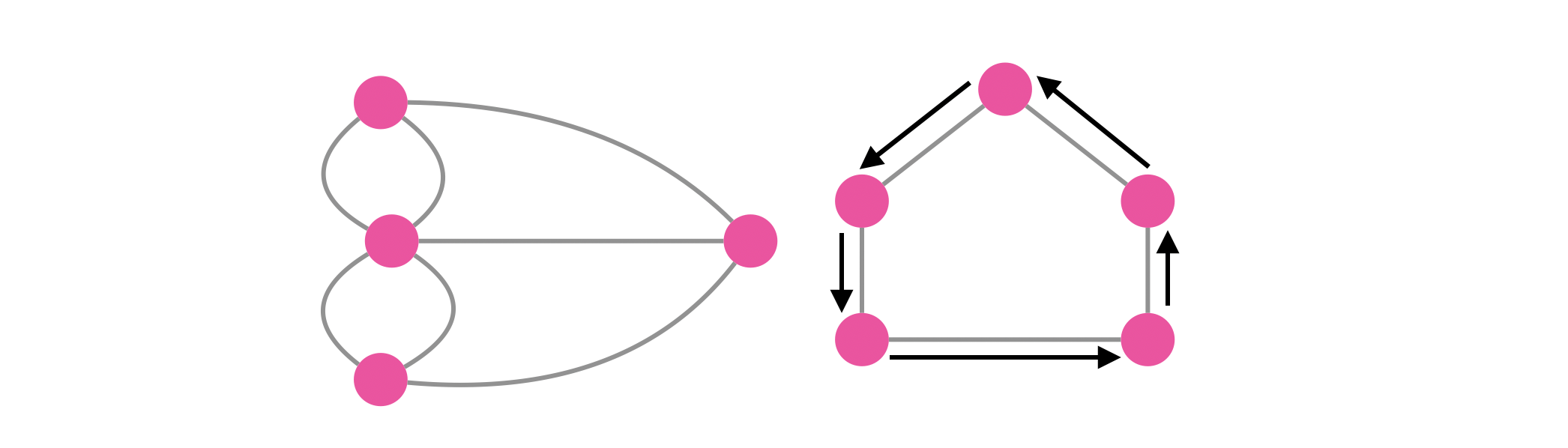

Let \(G=(V,E)\) be a connected undirected a graph. An Eulerian path is a path in a graph that traverses each edge exactly once and an Eulerian tour, circuit or cycle is an Eulerian path that starts and ends at the same vertex. Note that in both definitions, we can traverse any vertex more than once. It is named after Euler because in 1736 Euler proved that crossing all the seven bridges in Königsberg without crossing any bridge more than once is impossible (left figure). For more details, refer to this Wikipedia article.

Let \(G=(V,E)\) be a connected undirected a graph. An Eulerian path is a path in a graph that traverses each edge exactly once and an Eulerian tour, circuit or cycle is an Eulerian path that starts and ends at the same vertex. Note that in both definitions, we can traverse any vertex more than once. It is named after Euler because in 1736 Euler proved that crossing all the seven bridges in Königsberg without crossing any bridge more than once is impossible (left figure). For more details, refer to this Wikipedia article.

When do we have an Eulerian tour?

| Let \(G=(V,E)\) be a connected undirected graph. \(G\) has an Eulerian tour if and only if every vertex in \(G\) has an even degree. |

In the left figure above, it’s impossible to have an Eulerian tour since not every node has an even degree. However, the right figure has an Eulerian cycle and every node is of even degree.

Proof:

Let \(G=(V,E)\) be an undirected graph. We’ll prove both directions below,

\((\Rightarrow)\): Since \(G\) has an Eulerian cycle, we must traverse at least two edges every time we pass through a vertex except for the start and end vertex. This means that the degree of these vertices must be even. Since the start and the end vertex are the same, then this vertex must also have an even degree.

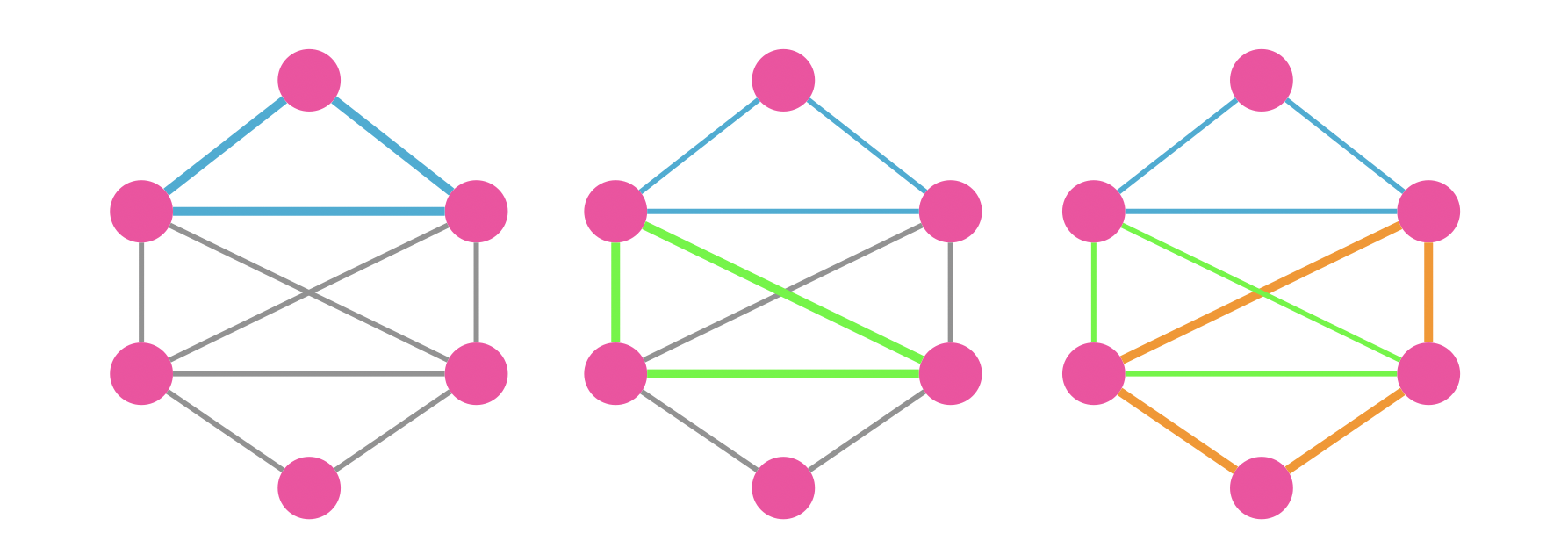

\((\Leftarrow)\): Start traversing at an arbitrary vertex \(v\). Since all the vertices are of even degree and \(G\) is connected, then we are guaranteed to return to \(v\) and we cannot get stuck at any other vertex. Let \(u\) be any other vertex than \(v\). Suppose we get stuck at \(u\). We claim that it is impossible, since \(v\) and the node we get stuck at will both be of odd degree and this is a contradiction to our assumption of all nodes having even degrees. After we return, we would have constructed a cycle in \(G\), call it \(C\). if every edge in \(G\) was in \(C\), then we are done. Otherwise, we must have some vertices in \(C\) that still have edges which were not traversed because \(G\) is connected. Choose a vertex and start traversing the remaining edges. We are again guaranteed to return to the same vertex because of the even degree property.

We can combine both cycles to form a bigger cycle. We can then repeat the same steps until no edges are left in \(G\). We are able to find all cycles and merge them since \(G\) is connected. Therefore, the cycle must be an Eulerian cycle as we wanted to show.

We can combine both cycles to form a bigger cycle. We can then repeat the same steps until no edges are left in \(G\). We are able to find all cycles and merge them since \(G\) is connected. Therefore, the cycle must be an Eulerian cycle as we wanted to show.

Implementation

Assuming every node is of even degree, it is clear that the way to discover an Eulerian cycle is by discovering the cycles one at a time and then merging all cycles together (from the proof above). This sounds hard. Fortunately, there is a really smart idea of using two stacks, one to traverse the current cycle and one that collects all the nodes in the final big cycle. This makes the algorithm run in only \(O(E+V)\) time, which is fantastic!

while (!stack.empty()) {

int current_node = s.top(); s.pop(); // pick some node

// now traverse it's edges

while (!graph[current_node].empty()) {

// (a) consider an edge between the current node and any of its neighbors

Edge *edge = graph[current_node].front(); graph[current_node].pop();

// (b) if it's used then we'll check another. If it's not then mark it used

if (edge->used) {

continue;

}

edge->used = true; // mark it used

// (c) push current_node back on the stack so we can go back to it (backtrack to it)

s.push(current_node); // push current_node

// (d) move to the other end of edge to process it

current_node = other_end(current_node, edge);

}

// this node is now part of the big final cycle

cycle.push(current_node);

}The best way to proceed with this algorithm is with an example.

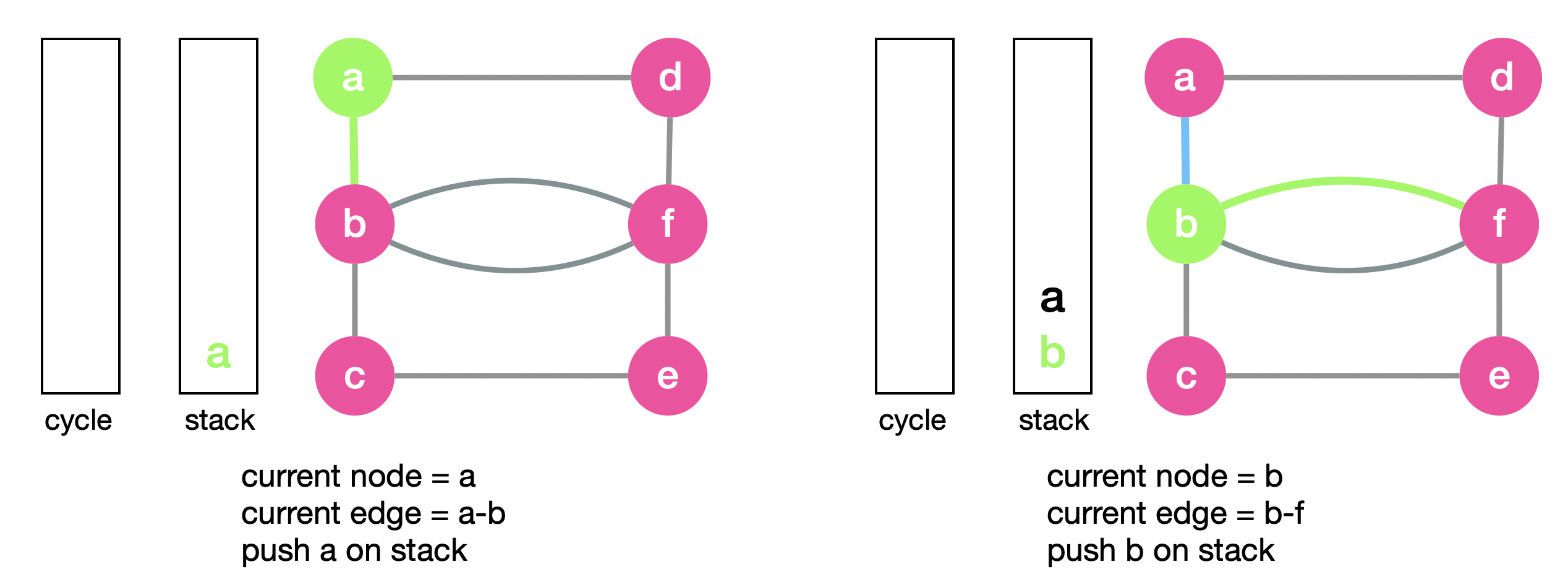

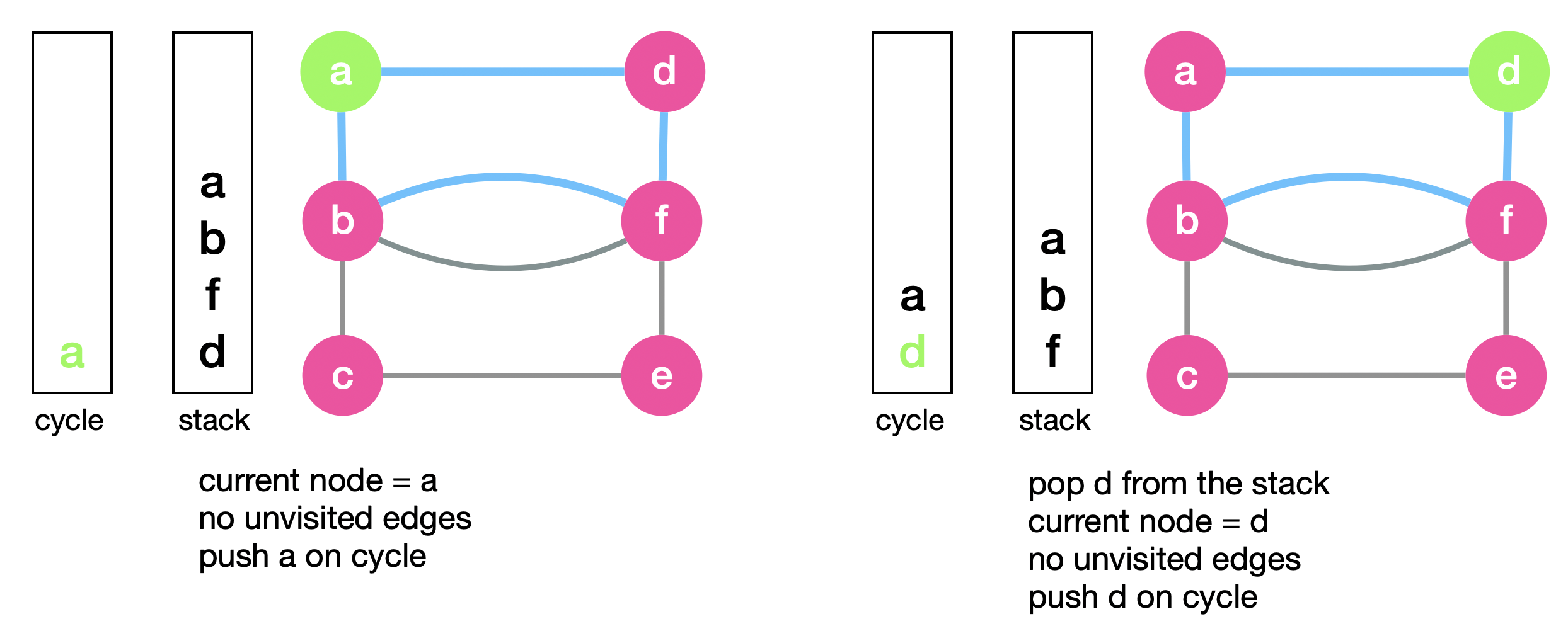

We initially push any node of choice on “stack”, we pick \(a\). We then pop a node from the stack and set the current node to \(a\). We then proceed to traverse the cycle starting at \(a\). We do so by selecting one of its unvisited edges. We pick the edge \(a-b\) and mark it as used. We then push \(a\) on “stack”. We switch the current node to the other end of the edge which is \(b\). We traverse an unvisited edge incident to \(b\). This time it’s \(b-f\).

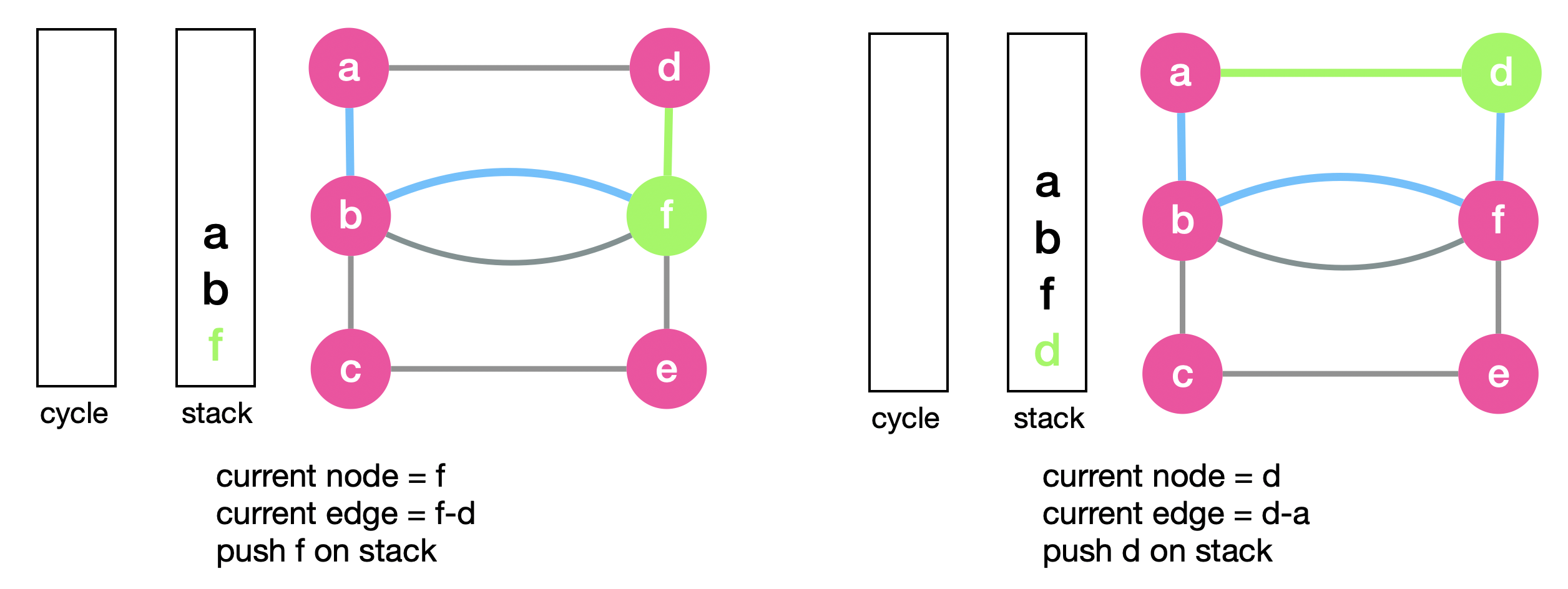

We repeat the above steps and set the current node to \(f\) and pick \(f-d\). We then move to \(d\) and pick \(d-a\), show in the figures below,

When setting the current node to \(a\), this time we don’t have edges to traverse. At this point it means that we reached a cycle. This cycle is “a-b-d-f”. So now we want to push this cycle onto “cycle”. We push \(a\) and then pop \(d\) and push it as well.

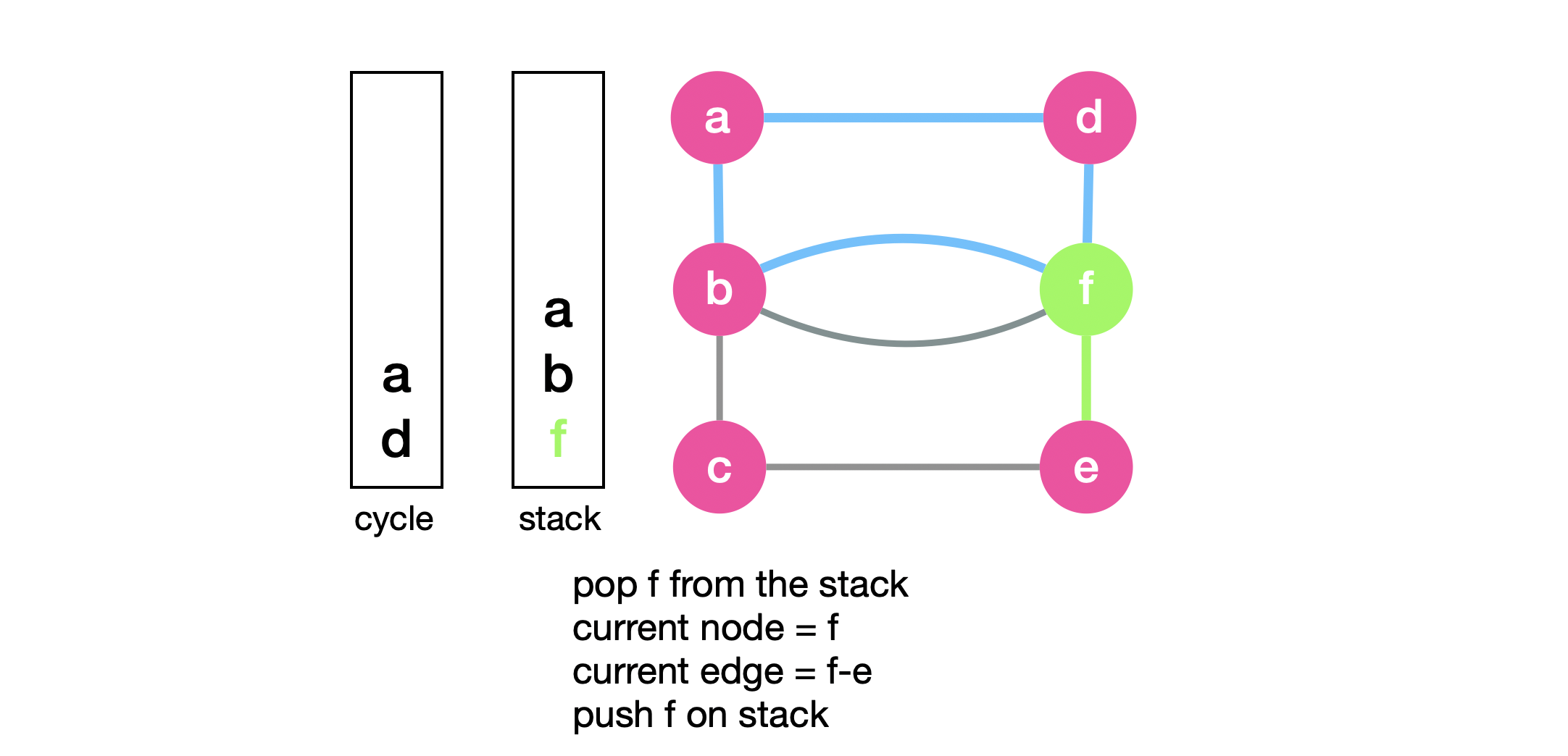

We next pop \(f\) in order to push it as well. However, this is where the magic happens. \(f\) has unvisited edges. This means that there must be a new cycle that starts at \(f\). Instead of pushing \(f\) to complete the original cycle “a-d-b-f”, we explore this new cycle first, push it and then go back to complete pushing the original cycle! We set the current node to \(f\) and start traversing this new cycle by traversing \(f-e\).

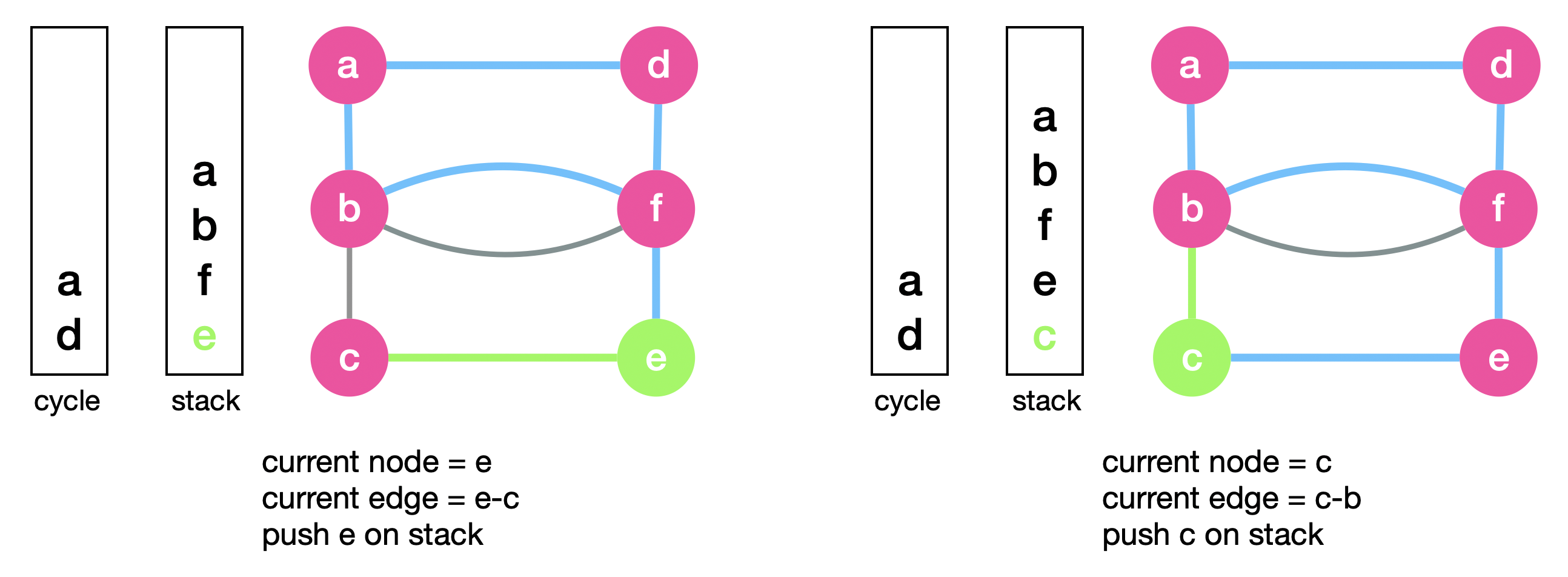

We repeat the same steps by pushing \(f\) back on “stack” and setting the current node to \(e\). We then explore \(e-c\) and push \(e\) on “stack”. We then explore \(b-c\) and push $$c$ on “stack”.

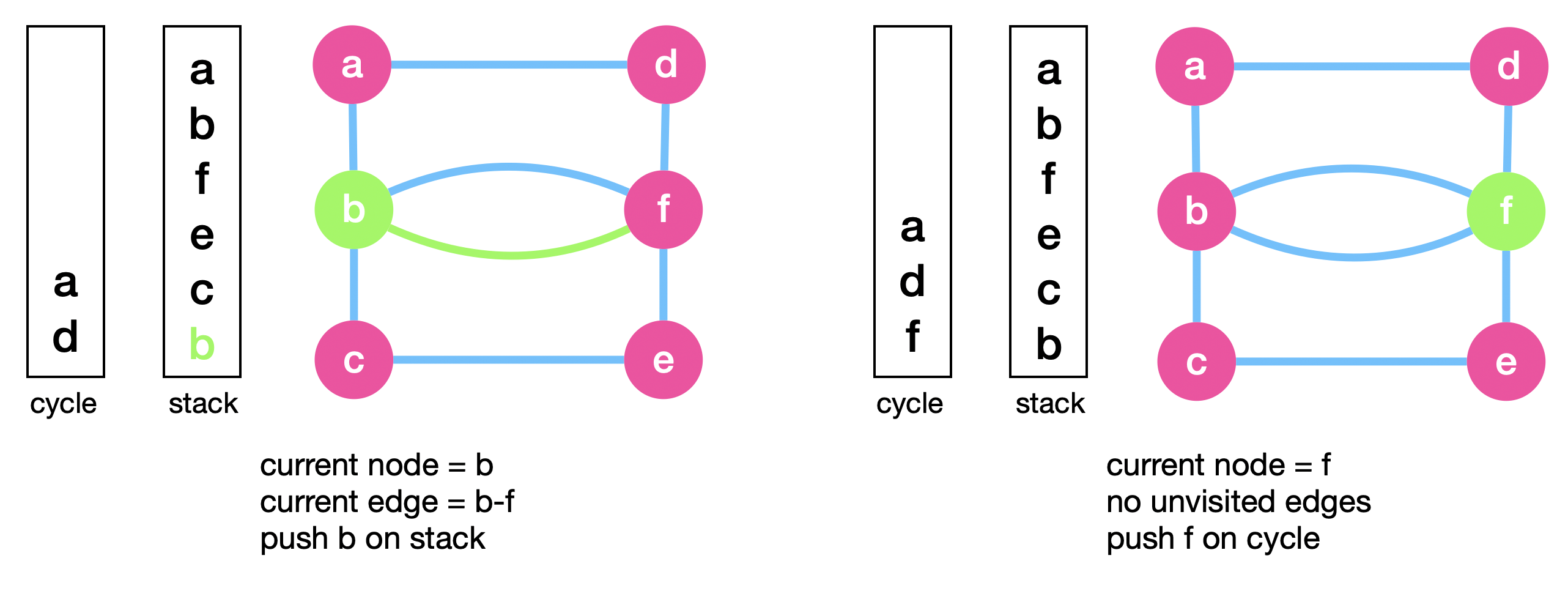

We set the current node to \(b\) below and explore \(b-f\). Finally we set the current node to \(f\) and this is where no longer have unvisited edges, meaning that we reach the end of the cycle we’re traversing.

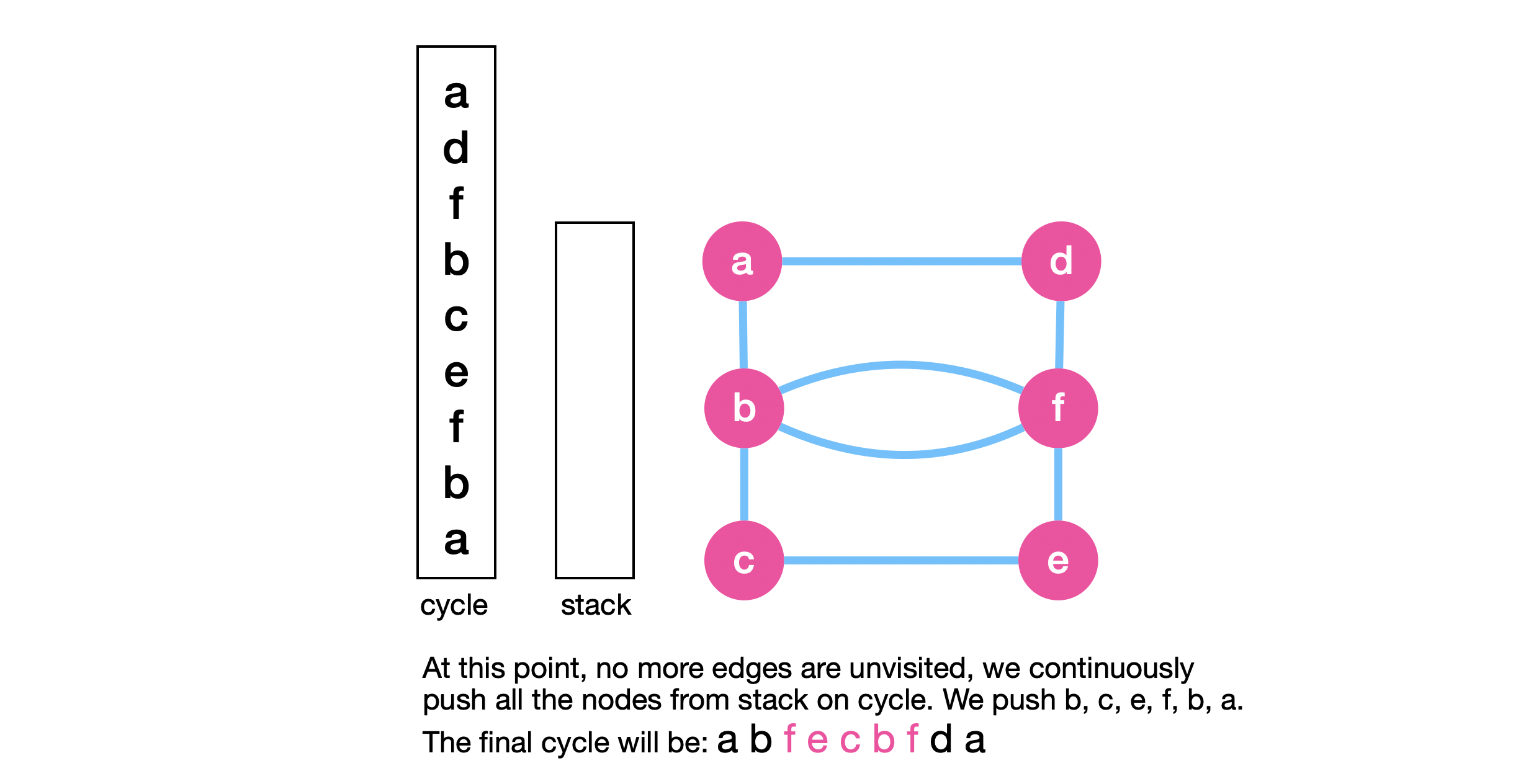

We start popping the nodes from “stack” and pushing them onto “cycle”. We stop this process if we arrive at any node with unvisited edges. However, this time we don’t see any more unvisited edges and we end up pushing the whole cycle plus the original cycle on “cycle”. And we’re done!

We start popping the nodes from “stack” and pushing them onto “cycle”. We stop this process if we arrive at any node with unvisited edges. However, this time we don’t see any more unvisited edges and we end up pushing the whole cycle plus the original cycle on “cycle”. And we’re done!

What about directed graphs?

Similar to the undirected case. Let \(G=(V,E)\) be a strongly connected graph. An Eulerian path is a path in a graph that traverses each edge exactly once and an Eulerian tour is an Eulerian path that starts and ends at the same vertex. Moreover,

| \(G\) has an Eulerian tour if and only if for every vertex \(v\) in \(G\), in-degree(\(v\)) = out-degree(\(v\)). |

Proof:

TODO